Review of The Strategy of Denial by Elbridge A. Colby (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021)

The age of Washington’s post Cold-War global hegemony has come to an end, as the United States enters a new era of great power competition with China. Many key American allies are exposed to Chinese military power and political influence. Consequently, it is imperative for Washington to adopt a defense strategy that counters Beijing’s recent aggressions and encroachments, especially against Taiwan. Weaving international relations theory with historical case studies and analyses of other countries, Elbridge Colby’s The Strategy of Denial explains how the United States can organize its foreign policy to address an increasingly threatening China. [1] Specifically, Colby advises the United States to organize an “anti-hegemonic coalition” in Asia to resist Chinese encroachment of Taiwan, which he argues is Beijing’s first step in a “focused and sequential strategy” to achieve global predominance.

To frame the crisis in Taiwan and the United States’ defense strategy, Colby organizes his book around specific terms in international relations. He begins by explaining defense initiatives that safeguard American interests, then considers other countries besides Taiwan, and finishes by addressing the implications of his approach. He draws from press conferences, special reports, and research papers to inform his conclusions about recent developments while supporting his arguments with historical illustrations. References to the Civil War, both World Wars, classical empires, and the formation of European states undergird his realist conception of how states behave.

Alongside Russian animosity towards the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), one of Washington’s principal concerns today is a Chinese attempt to invade Taiwan. This could, as Colby argues, begin a domino effect whereby China gains regional predominance and eventually global hegemony. Conquering Taiwan would give Beijing command of the East and South China Seas, enriching its trade and reinforcing its credibility on the Asian continent. China would continue its incremental strategy, with bolstered economic might, targeting vulnerable neighbors.

Beijing’s ambitions threaten American interests. The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) violations of the rights of religious minorities and its state-controlled economy clash with American ideals of free peoples and free markets. [2] If China establishes hegemony in Asia, the United States stands to be marginalized from the markets of the Eurasian supercontinent. This could soon be followed by European acceptance of Chinese political pressure and influence. Furthermore, if Washington fails to defend Taiwan, the loss of credibility would be irrecoverable, and other Asian democracies previously aligned with the United States would gravitate towards China. Nevertheless, as I will discuss in this review, political and ethical values must reinforce the American response to China’s expansion, a fact that Colby neglects, as he principally focuses on military strategy and the construction of alliances.

The main priority of the United States must be to convince its allies that there are ample reasons to resist China’s current trajectory. Other Asian countries are beginning to speak up about Taiwan and the profound repercussions that an invasion would have. Japan has recently articulated that Taiwan, a key democratic state, must be protected from Chinese attacks. [3] While Tokyo should still dedicate a larger portion of its GDP to defense, this represents a significant shift in Japan’s public communiqués.

To accelerate this trend in other countries, the United States must present China as the belligerent actor in the ongoing conflict. Colby cites Abraham Lincoln’s strategy of goading Southern troops into firing the first shot at Fort Sumter as an example of portraying the enemy as a prejudicial entity. The United States can apply this technique to fortify an anti-hegemonic coalition. If pivotal states like India, South Korea, Vietnam, Japan, and the Philippines feel sufficiently threatened by Chinese actions, they will join forces with the United States. Asia lacks a multilateral alliance system like NATO, highlighting the need for Washington to step in and execute a “binding strategy” that keeps the coalition united. If China is perceived as instigating conflict, suggests Colby, there is an increased chance that the binding strategy succeeds.

Consequently, Washington must manage its communication with Taiwan to avoid giving China justification for an invasion. Any message that could provoke a belligerent Chinese response should be relayed privately between the United States and Taiwan. If the CCP can point to a specific statement as reason for its aggression, other countries may blame the United States for the subsequent destabilization and hesitate to form a coalition.

Reflecting on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I found Colby’s discussion of “simultaneity” timely. In focusing its defense strategy on China, the United States must not neglect the plight of other sovereign nations such as Ukraine. However, Washington must also keep in mind that a Russian invasion is drastically different from Chinese aggrandizement. While European countries have suffered from a lack of coordination, many are prepared to respond to a Russian assault and assume a notable portion of the defense initiative alongside the United States. Germany, long anxious to preserve friendly relations with Russia, has now coordinated with the United States in levelling sanctions on Russia and increasing its defense capabilities. [4] Governed by a new coalition that intends to be tougher on Russia, the Germans are prepared to absorb economic consequences from Moscow for the sake of European security. [5] Spain, Belgium and the Netherlands sent military supplies to Ukraine shortly after the conflict erupted, while French President Emmanuel Macron has proposed reshaping a new European alliance system. [6] The United Kingdom, by pledging to send military aid to Eastern European countries, has also demonstrated its resolve in the face of Russian demands. [7] Owing to its alliances, the United States is not alone in facing Russia’s assault on the freedom of small states in Europe.

Taiwan, however, is not backed by a comparable multilateral alliance. Asian nations have not been as outspoken as NATO members when defending a targeted state. It is also highly unlikely that Washington’s allies in the Indo-Pacific will accept defensive weapons on their soil to avoid destabilizing their relationship with China. [8]

Although China maintains historical claims over a variety of territories and sea lanes, including a part of the South China Sea that would infringe on the Philippines’ rights, Taiwan will come first in the “systemic regional war.” [9] Thus, the United States must stress the importance of forming an anti-hegemonic coalition which agrees to dedicate resources principally toward Taiwan in the early stages of its development. The United States must defend Taipei at all costs while navigating a sensitive diplomatic game; even a simple invitation to bring Taiwan to a democracy summit is enough to inflame China. [10] If other nations pledge their support for upholding the status quo, like Japan has done, China will be dissuaded from launching an invasion.

The United States’ role must be grounded in preserving the current state of affairs in the South China Sea only when necessary. Colby pictures the United States as the external cornerstone of an anti-hegemonic coalition, seeking to distance itself from small-scale disputes as long as its allies can fend for themselves. There is no reason for Washington to begin using more provocative, direct language when engaging with China. However, surges in Chinese bellicosity, such as Beijing’s decision to reject the existence of the median line after flying two jet fighters 43 nautical miles into Taiwan’s side, cannot be overlooked by the United States. [11] Colby’s book would have benefited from greater discussion of the equilibrium between avoiding minor disputes and rising to major threats. Each case is discussed separately even though both strategies need to coexist when dealing with China.

Washington must prepare for the worst-case scenario despite its undesirable nature: war with China. Without adequate preparation, the United States runs another risk to its international reputation. The technological gap between American and Chinese military forces is closing. Last November, a Chinese hypersonic missile test went around the world; something the United States has not yet achieved. [12] If Washington is forced to resort to war, it cannot risk a head-to-head confrontation with China without the backing of its allies.

One tangible way for Washington to prepare for this unfavorable scenario is to build on its recent multilateral security successes, above all the Australia, United Kingdom, and United States trilateral security pact (AUKUS), to coordinate an alliance structure in defense of Taiwan. AUKUS is an agreement for the United States and United Kingdom to supply the Australians with advanced nuclear-powered submarines. By bolstering Australia’s naval capabilities, it can afford to take a stronger position against Chinese aggression and integrate more effectively into American military strategy. Concluding similar agreements with Japan, India, and South Korea would yield similar benefits.

Though Colby correctly identifies the seriousness and urgency of the threat that Beijing represents, he fails to adequately account for China’s oppressive regime and the role values ought to play. The book rarely deviates from military principles, making only a few scattered remarks about the importance of ideological divergence. Colby takes a realist approach to Washington’s defense strategy, prioritizing military might and strength over ideological values. In my view, he is mistaken to do so. The United States should not solely behave as a reactive military power while China continues to commit human rights atrocities. Harnessing the energy of the American people to win the competition with China will require more than military jargon. Policymakers must emphasize how China’s authoritarianism threatens American principles across the world as they did during the Cold War. [13] Furthermore, readers looking for a comprehensive assessment of the international sphere may be disappointed. Few of the terms or assessments included in the book entertain the prospect of international institutions mitigating conflict due to its realist outlook.

Colby’s strength is that he regularly underlines that the United States’ defense strategy must account for different outcomes. Washington’s main objective should be to preserve the status quo since this upholds balance and peace. The current gridlock between the United States, China, and Taiwan, while tense, is better than war. This does not mean the United States should neglect planning for conflict. Framing a Chinese invasion as a danger to allies’ interests, forming an anti-hegemonic coalition that safeguards Taiwan’s autonomy, and improving allied defense capabilities should constitute the United States’ military strategy in this great power competition.

To prevent Chinese hegemony in Eurasia and all the dangers it forebodes, Washington must prioritize Taiwan and communicate clearly with its allies. Through this strategy, American ideals and trust in the United States will continue to flourish for another generation.

Axel de Vernou ’25 is an Officer of Communications for the AHS chapter at Yale University, where he aims to major in Global Affairs.

—

Notes:

[1] Elbridge A. Colby, The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021).

[2] “China’s Disregard for Human Rights,” U.S. Department of State, https://2017-2021.state.gov/chinas-disregard-for-human-rights/index.html#ReligiousFreedomAbuse.

[3] Ryan Ashley, “Japan’s Revolution on Taiwan Affairs,” War on the Rocks, 23 November 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/11/japans-revolution-on-taiwan-affairs/.

[4] Andrea Shalal, “Nord Stream 2 Pipeline Under Threat if Russia Invades Ukraine-U.S. Officials,” Reuters, 7 December 2021, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/us-has-understanding-with-germany-shut-nord-stream-2-pipeline-if-russia-invades-2021-12-07/.

[5] Vladimir Afanasiev, “Germany Changes Tack on Nord Stream 2,” Upstream, 27 January 2021, https://www.upstreamonline.com/politics/germany-changes-tack-on-nord-stream-2/2-1-1158657.

[6] Priyanka Shankar, “Why Can’t Europe Agree on How to Deal with the Ukraine Crisis?,” Aljazeera, 26 January 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/26/why-europe-cannot-agree-on-russia.

[7] Sarah Wheaton and Annabelle Dickson, “UK Eyes ‘Biggest Possible’ Military Support to NATO over Ukraine,” Politico, 30 January 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/uk-big-military-support-nato/.

[8] Jeffery Hornung, “Ground-Based Intermediate-Range Missiles in the Indo-Pacific: Assessing the Positions of U.S. Allies,” RAND Corporation, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA393-3.html.

[9] Oriana Skylar Mastro, “How China is Bending the Rules in the South China Sea,” The Interpreter, 17 February 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/how-china-bending-rules-south-china-sea.

[10] Alexandra Jaffe, “U.S. Invitation of Taiwan to Democracy Summit Angers China,” AP News, 24 November 2021, https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-china-taiwan-democracy-43d29b3153e853bd5276d2784b91ac8b.

[11] J. Michael Cole, “China Ends ‘Median Line’ in the Taiwan Strait: The Start of a Crisis?,” The National Interest, 22 September 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/china-ends-%E2%80%98median-line%E2%80%99-taiwan-strait-start-crisis-169402.

[12] Chandelis Duster, “Top Military Leader Says China’s Hypersonic Missile Test ‘Went Around the World,’” CNN, 18 November 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/11/17/politics/john-hyten-china-hypersonic-weapons-test/index.html.

[13] Hal Brands and Zack Cooper, “U.S.-Chinese Rivalry Is a Battle Over Values,” Foreign Affairs, 16 March 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-03-16/us-china-rivalry-battle-over-values.

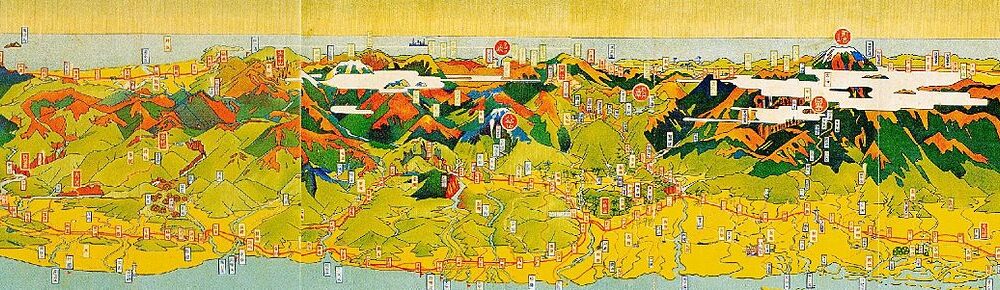

Image: “Taiwan daily news taiwan map,” by Taiwan daily News, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taiwan_daily_news_taiwan_map.jpg. This photograph is in the public domain in Japan because its copyright has expired according to Article 23 of the 1899 Copyright Act of Japan (English translation) and Article 2 of Supplemental Provisions of Copyright Act of 1970. This is when the photograph meets one of the following conditions: It was published before January 1, 1957. It was photographed before January 1, 1947. It is also in the public domain in the United States because its copyright in Japan expired by 1970 and was not restored by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act.