On 8 March 2022, the exchange rate of the Russian ruble hit its all-time low against the U.S. dollar and other major reserve currencies. Why? Tanks.

To be specific, Russian tanks, soldiers, helicopters, fighter jets, and conventional weapons of war deployed in Ukraine. While the Russian invasion of Ukraine did not surprise many military strategists and geopolitical experts, the response to the invasion has caught some off-guard.[1] When before has the use of an invading military been countered by closing payment rails to a commercial bank? Why would a Russian artillery barrage into Kharkiv receive a responding volley from Starbucks, Shell, and Little Caesars terminating business arrangements? The Russian military invasion of Ukraine has kicked off a series of responses from the West and its commercial entities that have led to the freefall of the ruble while generating conditions for the incipient implosion of the Russian economy. In other words, the West has recognized that dollars, tanks, and banks are inextricably linked and that eroding economic stability or financial prowess through economic warfare is one way to degrade military capacity and diminish operational efficacy.

The global economic warfare playbook that is being drafted and implemented by Western nations against Russia has a new feature: it is being executed en masse by both government and private entities. In general, though, economic warfare is not a new concept; it has been around since the inception of warfare itself. What is new, at least to the United States and the West, is the magnitude of scale in which individuals and private entities are helping wage economic war in response to conventional war. So, what does the economic warfare model look like during a cold war? Or what about for a war that we might not even acknowledge exists? The answer can be found by exploring Russia’s neighbor to the southeast—the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The CCP has been actively waging economic war against the United States and Western nations for roughly three decades. The CCP’s campaign plan is to grow its economy and modernize its military while simultaneously eroding the economic primacy and military prowess of the United States and many Western nations. While the Chinese and Russian theaters of economic warfare have different features because of stark contrasts in vulnerabilities and resources, there is also a significant amount of operational and tactical overlap. Assessing the successes of the economic warfare playbook that is being drafted in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine against the successes of the CCP’s economic warfare playbook against the West is very telling in which tactics work and to what extent. The CCP’s strategy is not in response to America’s use of tanks in China or against an allied nation. It is a deliberate, long-term policy to weaken the U.S. economy and military and to diminish Western influence in the Pacific and around the world. Whereas the United States is competing with the CCP economically, the CCP is engaging in economic warfare against the United States.

For the United States and its allies and partners to effectively respond to the economic war being waged against it by the CCP, the United States must first recognize that it is in an economic war with the CCP. Then, the United States should establish an Office of Economic Warfare and Competition (OEWC). This office should either be nestled under the Executive Office of the President, in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, or as a joint office similar to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. It will have the primary objective of understanding the economic battlefield, identifying the competitive advantages of each country in both theaters, mapping the gaps as well as existing resources, authorities, and relevant policies related to economic warfare, and coordinating and delivering effects against our adversaries. Establishing this office is the best chance the United States has to turn the tide back against the CCP on the economic battlefield.

Creating an office with a singular purpose that transcends disciplines (for example, national security, international relations, economics, etc.) and departmental objectives (for example, Commerce, Defense, Treasury, State, etc.) will give strategists, policymakers, and lawmakers the information required to create legislative or policy responses that thwart and counter how the CCP—or any adversary—weaponizes its economic capabilities to erode the economic primacy and military prowess of the United States. This office will have both defensive and offensive capabilities, but it must equally safeguard U.S. economic, legal, and free-market principles that have allowed America to thrive for centuries. Balancing the free flow of goods, services, ideas, people, and capital will be just as critical to the office as protecting U.S. national and economic security interests at home and around the world.

Defining Competition and Warfare in the Context of Economics

One of the primary challenges with designing and implementing policies to respond to economic warfare is delineating economic competition from economic warfare. While national economic competitiveness and economic warfare share some of the same characteristics, they have enough distinguishing traits to separate them from policy contagion. Conflating the two—which is easy to do—could lead the United States to apply the worst aspects of a ‘decoupling’ strategy while abandoning the healthy, free flow of goods, services, and capital that enrich both buyers and sellers in the global economy. If policymakers are not careful, the United States and the CCP will drag each other down rather than become more selective and disciplined in how they engage and partner with one another. The new OEWC can help prevent the United States from making a critical error early on by uniting departmental authorities into one convening forum that deconflicts policies or actions which might contradict one another, a regular occurrence in the federal government.

Competition and warfare are two distinct and contrasting applications of economics. The former is the traditional economic approach: increasing domestic output, growing factors of production, and expanding global market share to improve or strengthen competitiveness. The latter is the leveraging of economic tools, methods, capabilities, and resources to achieve geopolitical, strategic, and military objectives through non-kinetic means. The end goal of economic competition is to create and then lead an economic system that captures market value, production efficiencies, and enriches one’s populace. The end goal of economic warfare is to achieve strategic outcomes, overpower adversaries, and alter the global system to one’s advantage and to the detriment of an adversary or competitor. The difference between the two is cause and intent—economic competition might cause an erosion of economic productivity; economic warfare intends for an erosion of economic productivity. While each economic action a country takes may not independently rise to a threshold to constitute economic warfare, an accumulation of these activities when state-directed—because the intent behind the action is now nefarious—most certainly does.

Competition over economic systems at the ideological level does not constitute warfare. The Cold War is an exemplar of a conflict that had elements of economic warfare (for example, the Berlin Blockade, Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom), etc.), but the main crux of the conflict was an ideological competition regarding which economic system was superior: the Soviet Union’s communism or the United States’ capitalism. In large part, the military and economic aspects of the Cold War were kept distinctly separate. The Soviet Union’s economic pursuits during the Cold War were to expand its means of production to improve its economic posture, not cripple the United States’ ability to field helicopters or tanks. As a result of this experience, the United States still approaches military and economics as two separate instruments. On the other hand, much of the CCP’s commercial pursuits are dual-use technologies in support of military-civil fusion (MCF). This approach categorizes these economic activities as military-enabling, which elevates these activities into the category of economic warfare. The CCP’s actions in its economic model are distinct from the Soviet Union’s because the CCP, although also engaged in a competition of systems, is targeting economic activities to acquire capabilities or technologies that have been or can be militarized..

The CCP has telegraphed its MCF objectives and made pronounced overtures regarding its desire to control entire supply chains that contribute to MCF. The CCP has directed state-owned enterprises, commercial entities, and private citizens to operate in concert—as an army—with the CCP to acquire mature, critical technologies with significance to both economic interests and military operations.[2] Specifically, the CCP has relentlessly pursued dual-use technologies and applications such as lasers, batteries, drones, space systems, autonomous vehicles, and Global Positioning System (GPS).[3] In doing so, and deploying a whole-of-nation approach to support MCF, the paradigm shifts from competition of economic systems to engaging in economic warfare. The CCP’s whole-of-nation approach blurs the lines between who is working to support the economy and the military. Fusing these two together means that economic activities are indistinguishable from military objectives.

The Made in China 2025 (MIC 2025) strategy complements MCF. MIC 2025 is the CCP’s national strategy to target ten industries essential for China’s economic growth and technical maturation of indigenous capabilities. The overarching objective is to upgrade or advance China’s low-grade domestic manufacturing capabilities across the board.[4] All listed MIC 2025 targets have dual-use verticals and components, but none more obvious than aerospace equipment, ocean engineering, energy production and storage, and new materials (e.g., critical minerals, rare earth elements, etc.). The CCP’s appetite to obtain these technologies appears limitless. What is most concerning are the lengths the CCP is willing to go to get them.[5] To satisfy the lofty goals of MIC 2025, the CCP is executing a state-directed campaign to steal critical or emerging technologies; bribe elected officials or corporate leaders; deploy predatory capital in vulnerable markets; employ slave labor; and deliberately mislead, obfuscate, or conceal information from investors and business partners.[6] The CCP’s aspiration to control entire supply chains, manipulate global market conditions, fuse commercial production and military objectives is operationally economic warfare.[7] The CCP’s directed efforts to acquire technology are so widespread that in a 2019 poll from Consumer News and Business Channel (CNBC) one in five American Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) reported having had their Intellectual Property (IP) stolen by China within the past year.[8] Laws in China are written to compel corporate entities and individuals to act on behalf of the state.[9] Worst of all, courts in China recently established a legal precedent of anti-suit injunctions so that foreign entities accusing Chinese entities of IP theft have no legal recourse in China.[10] The CCP is taking a whole-of-nation approach to enhancing its economy and military to the detriment of those who engage in business with China.

The Office of the United States Trade Representative estimated in 2018 that roughly $225 billion to $600 billion of U.S. economic value is lost each year as a result of these practices.[11] That is roughly 2.5% of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) annually. General Keith Alexander, while serving as the Director of the National Security Agency, described this type of economic warfare as the “greatest transfer of wealth in history.”[12] At best, the United States was deprived of hundreds of billions of dollars in tax revenue that could have been used to shore-up underspending in education, improve access to healthcare in a rural part of America, modernize our infrastructure, or adjust sustainment costs on a defense platform. In addition to tax revenue lost, profits were lost, products were not manufactured, salary increases might have been withheld, and returns on investment stifled. Calculating the damage that the CCP’s economic war causes to America is hard to accurately quantify, but for comparison, the federal government spent $690 billion on defense and $1.2 trillion on healthcare across America in 2019.[13] It is difficult to impress the significance felt in everyday life by such deliberate economic erosion. Unfortunately, this is not a uniquely American problem.

An alarming example of the CCP waging economic warfare elsewhere comes from Lithuania. Recently, Lithuania allowed Taiwan to open a representative office in Vilnius, which the CCP viewed as a diplomatic rebuff to its ‘One China’ policy despite the Lithuanian government making CCP-supporting comments after.[14] In retaliation, the CCP sent Lithuania’s ambassador back to Vilnius and declared an import ban on products made in Lithuania. Because of the CCP’s ban and fears of a reduction in revenue from China, German auto-manufacturer Continental stopped using Lithuanian-manufactured parts in its cars. The result is that the Lithuanian economy has been damaged: accrued tax-base revenue on exports and income has been reduced, wages from terminated employees that would circulate back into the economy have been lost, and operating or capital expenditures that could have enhanced production lines or been allocated into Research & Development (R&D) are gone.[15] China receives an advantage (the same cars from Germany) and Lithuania receives a disadvantage (loss of tax revenue on wages and exports).

Lithuania currently has a population of 3 million; Germany has a population of 83 million; China has a population of 1.4 billion. Lithuania spends $1.37 billion (USD) on its military; Germany spends $53 billion (USD) on its military; China spends $252 billion (USD) on its military. Meaning China has roughly 1.397 billion more people than Lithuania and that China’s economy is 270 times the size of Lithuania’s.[16] So, at no point did Lithuania pose any meaningful military or economic threat to the CCP. The CCP knew this and decided to use its economic leverage over Germany as a pass-through for economic warfare against Lithuania for its perceived transgression against the CCP. This damaged Lithuania’s relationship with Germany, hurt Lithuania’s economy, and showed to others that the CCP can hit you when it wants. This type of detrimental economic activity is completely and distinctly different than sanctions, embargos, or other diplomatic tools. These types of economic warfare operations should only be used when there is actual monetary damage to a country, impending harm to an ally or partner, or in response to conflict or war (see Ukraine). Firing this type of economic bullet for such a trivial quarrel shows the CCP has successfully positioned itself to run future economic warfare operations or campaigns against smaller economies. The CCP’s willingness to deploy such an indiscriminate tool of national power for such a trivial matter is invariably problematic as it sets a precedent for nation-states to use disproportionate responses for diplomatic disagreements. While this response by the CCP is shocking when read as a simple fact-pattern, there are thousands of reports or cases of the CCP waging economic warfare operations around the world to aggrieve what it considers wrongdoings. A curious reader can access some of the most appalling stories of retaliation, espionage, and theft by CCP both unprompted and in response to a country, company, or person exercising free will that does not align with the CCP.[17]

The Lithuania case contributes to defining economic competition versus economic warfare. A more comprehensive definition comes from Dr. Howard Shatz of the RAND Corporation. In his 2020 paper “Economic Competition in the 21st Century,” Dr. Shatz succinctly framed economic competition into five categories: first, strategic competition in economics; second, economic competition beyond competitiveness; third, geopolitical competition with economic trade; fourth, competition over the system itself; and fifth, economic competition and the armed forces. [18] The CCP engages in all five types of economic competition listed, but the crux of relevance to economic warfare is competition over the system itself. While the CCP wants to increase its competitiveness and achieve geopolitical objectives, it ultimately wants to upend the global economic system which currently allows for the United States to operate as the economic and military hegemon.

The economic actions and illicit activities directed by the CCP in pursuit of MCF and MIC 2025 show an evolution in how aggressive the CCP can be when waging its economic war. The magnitude of economic value loss and the scope of military-capable technologies that are being stolen and forced out of the United States and into China is of such a scale that it can only be surmised as economic warfare and not economic competition. As the CCP continues to move its economic warfare campaign further into the boardroom, the more the CCP weaponizes its economy. And, as highlighted by the Lithuania example, the entire world is in the CCP’s crosshairs.[19]

Economic Security = National Security; Economic Competition ≠ Economic Warfare

As the 2017 National Security Strategy concisely states, “economic security is national security.” Said differently, U.S. military primacy is ensured by U.S. economic primacy. America’s laws and values have allowed for a thriving American economy that is the world’s leader of innovation, production, and economic output. Our economic posture and exceptionalism have created a substantial financial base from which the United States draws tax revenue to pay for its military and global influence. This same economic base also finances innovation for cutting edge technologies and capabilities; entices and incentivizes the brightest minds from around the world; and has helped generate decades of advanced industrial manufacturing and output. Thus, the central pillar of the United States’ national security apparatus and posture—both home and abroad—rests on a robust and growing economy. Any degradation of this structure such as lost wages and reduced tax revenue, increased manufacturing or sustainment costs, fragile or strained supply chains, or an unfavorable reallocation of resources means that economic security is diminished, and thus national security is impinged.

National security experts and military strategists in the United States think about the term “warfighting domain” too narrowly and less dynamically than adversaries. Traditionally, there are five warfighting domains against which the U.S. military organizes, trains, equips, resources, and conducts operations: air, land, sea, cyber, and space. To our detriment, this organization has shaped the pedagogy by which we teach military strategists and has tinted the lens through which we view national security. This framing has caused national security leaders to neglect to recognize economic warfare as a warfighting domain, resulting in decades of erosion to America’s economic posture and national security. Curiously, strategists place a great emphasis on protecting the defense industrial base and increasing supply chain resilience to support the warfighting domains, yet make scant reference to the ensuring of the economic engine that powers them. Policymakers are past due in asserting economics as a warfighting domain so that lawmakers can provide the adequate authorities and resources to economic and military strategists to address this type of persistent asymmetric threat from America’s adversaries.

Right now, there is a cacophony of noise in Washington and around the world about the CCP. Specifically, about how the CCP is deploying predatory capital, committing widespread IP theft, shameless industrial espionage, and exploiting dual-use technologies for its MCF objectives. What appears to consistently accompany this clamor is the absence of any meaningful way forward. The news is teeming with headlines stating that “stronger dialogue” or an “economic framework” is how the United States will take on the CCP. If the CCP were competing with the United States in the traditional economic sense, then those terms would provide an appropriate response. But these statements miss the mark, failing to adequately address how the CCP is fighting the United States. As currently constructed, there is no way for the U.S. government or economy to address the CCP’s asymmetric threats; trade negotiations, tariffs, and modest alterations to U.S. economic policy will not produce a solution.

Bi-partisan recognition of the ‘economic security is national security’ doctrine has occurred, but it has not resulted in tangible change in the U.S. national economic security apparatus. President Biden’s Indo-Pacific Strategy specified that “the PRC is combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological might… and seeks to become the world’s most influential power.”[20] Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) stated “it’s that the kind of threat is unlike anything the U.S. has ever before faced—a powerful economy with coercive, state-driven industrial policies that distort and undermine the free market, married up with an aggressive military modernization…”[21] And Senator Bob Casey (D-PA) recently said “we’re in an economic war, whether we want to use that language or not.”[22] All are in reference to the CCP. These comments imply acceptance that economics and the CCP’s pursuit of global economic military dominance are one and the same. However, the United States has not put the new understanding into practice. It has not created an office, agency, or department to address this threat. Lawmakers and policymakers have not even granted new or expanding authorities to an existing agency or department, nor given resources to meaningfully address this national and economic security issue. In order to counter the CCP, move back to economic competition and away from economic warfare, and protect American values, the United States must take on this contested domain with the same level of resourcing and strategic national security support as any of our other warfighting domains. Why? Because all of the traditional and modern warfighting domains are wholly dependent upon the health and resilience of the U.S. economy.

The reason economic security is so critical to national security is derived from a mathematical function and empirical measurement within the study of economics. For instance, if the United States requires an aircraft carrier to maintain or increase national security and expects its lifecycle costs to be X, Congress can allocate the necessary funds to the Navy to build, maintain, and operate the aircraft carrier over its lifecycle. However, if over a period of time there is a significant decrease in tax revenue or increase in sustainment and operational costs, then the aircraft carrier costs Y (or X+). Congress then has to reallocate resources from another program—placing a strain on that program’s finite resources—or hope the Federal Reserve will print more money to offset the shortcoming for Y. This arrangement is financially unsustainable as national security costs will continue to outpace the United States’ financial resources.[23]

As more variables that are beyond the United States’ control, such as the cost of raw materials or technologies, are brought into the economic model, the costs continue to calibrate to those prices and the problem metastasizes into more costly government programs. Returning to the economics and mathematics of long-term financial outlays quickly shows that the model inevitably breaks and sustaining and operating the military becomes untenable, and worse, other government programs break down, too. The path towards both economic and national security insolvency is already being walked, but it is significantly compounded and exacerbated by the economic degradation arising from the type of economic warfare being waged by the CCP against the United States.[24]

The various consequences are a world in which the United States is not the dominant reserve currency, the desired trade partner, and no longer leading the world with regard to the rule of law, human rights, and international institutions and organizations. Whereas the United States is stuck in approaching this contested domain either as a traditional military problem or through the lens of economic competition, the CCP views it as an economic campaign, a brilliant strategy so long as the CCP is able to operate uncontested. The current outcome based on this environment is that the CCP replaces the United States as the world’s leading economy, the CCP degrades the U.S. military, and the CCP constrains its primary competitor’s future economic outlook — all without firing a shot.

If the United States does not stand up to the CCP’s economic warfare today, then it will become too costly and too complex for the United States to sufficiently do anything about it tomorrow. If waging an economic war against Russia while it controlled only 5% of worldwide oil exports was problematic for global economic stability in 2022, then waging an economic war against the CCP in another decade when it controls 90% of global critical minerals and holds more than $1T (USD) of U.S. debt is unthinkable.

No More Prizes for Predicting the Rain; Only Prizes for Building the Ark

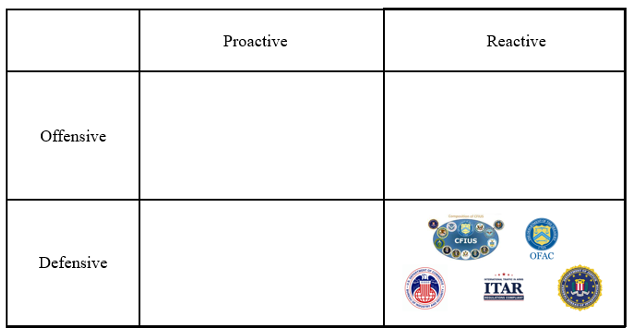

As much as this issue centers around the actions of the CCP, much of this problem requires the United States to look inward. There is no department, agency, or office within the U.S. government with the authority to meaningfully conduct either proactive–defensive or offensive economic activities to counter the CCP (see chart on next page). Policymakers do not have any viable options to engage in the economic warfighting domain. In contrast, there are a host of U.S. government agencies and departments working actively to advance competitive economic interests, such as the Department of Commerce (DOC), the Department of State (DOS), or the Small Business Administration (SBA). Each of these entities promotes U.S. economic interests at home and abroad to increase global commerce. There are also entities designed to protect our critical technologies or supply chains domestically, such as export controls (Export Administration Regulations), arms and munitions controls (International Traffic in Aarms Regulations), and foreign investment screening (Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)). However, CFIUS is largely a voluntary process and export controls allow for self-assessment by sellers. Both tools have nuanced authorities that limit the purview of their scope and thus efficacy in economic warfare.[25] There are defense-reactive capabilities such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or the Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC), but the actions conducted by those entities are generally reactionary to an event and thus not an appropriate tool for much of the CCP’s activities. The other relevant economic tools available are generally limited to the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Export-Import Bank (EXIM); all of which operate with small sums of cash and strict limitations on the types of investments they can pursue. None of the aforementioned departments, agencies, or offices work in the economic warfare domain as it relates to the CCP.

The mission of the OEWC will be to coordinate the economic resources and financial capabilities of the United States in a complementary structure that allows for a coherent response to the economic actions being taking by the CCP. Once matured in the United States, the mission of the OEWC should be expanded to include allies and partners. The OEWC should be granted specific authorities to make strategic investments in infrastructure and technology, issue loans and loan guarantees, create a forum to leverage the nearly $2 trillion dollars of private capital on the sidelines in the United States, and work to propose favorable tax, trade, and tariff regimes that incentivize a whole-of-country approach within the United States to counter the CCP. This strategic shift will allow the United States to support national champions in the marketplace, make strategic investments at home and overseas, and take significant risks the way the United States did during the space race or Operation Warp Speed.

In general, and in keeping with our laws and traditions, the U.S. government has stayed out of the way of private enterprise and global commerce. Our strict laws categorically limit the intrusion of government into the private marketplace beyond a law enforcement function or in a regulatory capacity. This approach to economics is acceptable so long as your supply chains do not run through your adversaries’ factories and your trade partners do not wage economic warfare against you. Unfortunately, that is the current environment and our stationary posture within government is why we are watching an erosion of our economic primacy at home and overseas. We need to shift our thinking around both warfare and economics the way our adversary has done. For the United States to remain the world’s superpower—or even competitive over a longer time series—we must decide that economics is a contested domain that requires the same level of resourcing and strategic national security support as any of our other warfighting domains. Recognition of the ongoing conflict and the creation of the OEWC will grant the United States the ability to cohesively plan, resource, operationalize, and deliver effects against the CCP—and all adversaries—in the economic domain.

The decline of the U.S. economy and the softening of our national security posture is a choice for us to make. While external factors can pressure and dissuade us from choosing correctly, ultimately it is on us to define the threat for what it is and equip ourselves with the necessary tools to respond and protect our interests. If we do not, the physics of economics are too great for us to counter and authoritarianism will eventually triumph over democracy, and we go by the way of the Romans. What the world has done on the economic battlefield against Russia is not currently scalable or repeatable as the CCP challenge is markedly different. Establishing the OEWC is a critical step for the United States to normalize a whole-of-government or whole-of-nation approach that will give U.S. policymakers options and tools to direct government support around national economic security objectives to effectively take this threat head on.

David Rader is a national economic security lawyer. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of his employer or any entities of affiliation with the author.

David Rader is Deputy Director in the Office of Foreign Investment Review at the Department of Defense. David’s portfolio focus is on national economic security, foreign direct investment, trade policy, and matters under the purview of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). He was a 2020-2021 Security and Strategy Seminar China fellow, a 2021-2022 Russia fellow, and is a 2022-2023 Defense fellow.

_________________

Image: 1st CAB Seeks Better Reaction Time and Lethality With Modernization, 25 February 2010, from dvidshub.net. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1st_CAB_Seeks_Better_Reaction_Time_and_Lethality_With_Modernization_DVIDS257062.jpg, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Kate Davidson & Eliza Weaver, “The West Declares Economic War on Russia,” POLITICO, 28 February 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.politico.com/newsletters/morning-money/2022/02/28/the-west-declares-economic-war-on-russia-00012208.

[2] “Billion-Dollar secrets stolen: Scientist Sentenced for Theft of Trade Secrets,” FBI, 27 May 2020, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/scientist-sentenced-for-theft-of-trade-secrets-052720.

[3] Samantha Ravich & Annie Fixler, “The economic dimension of great-power competition and the role of cyber as a key strategic weapon,” The Heritage Foundation, 30 October 2019, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.heritage.org/military-strength-essays/2020-essays/the-economic-dimension-great-power-competition-and-the-role.

[4] Christopher Wray, “Countering threats posed by the Chinese government inside the U.S.,” FBI, 31 January 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.fbi.gov/news/speeches/countering-threats-posed-by-the-chinese-government-inside-the-us-wray-013122.

[5] Jeff Daniels, “Chinese theft of sensitive US military technology is still a ‘huge problem,’ says defense analyst,” CNBC, 8 November 2017, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/08/chinese-theft-of-sensitive-us-military-technology-still-huge-problem.html.

[6] Brenda Brockman Smith, “China’s Use of Forced Labor in Xinjiang – A Wake-Up Call Heard Round the World?” Council on Foreign Relations, 26 August 2021, retrieved 15 March 2022, from https://www.cfr.org/blog/chinas-use-forced-labor-xinjiang-wake-call-heard-round-world; Christopher Burgess, “NCSC warns industry, academia of foreign threats to their intellectual property,” CSO, 5 November 2021, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.csoonline.com/article/3641972/ncsc-warns-industry-academia-of-foreign-threats-to-their-intellectual-property.html.

[7] Christopher Wray, “The threat posed by the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party to the economic and national security of the United States,” FBI, 7 July 2020, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.fbi.gov/news/speeches/the-threat-posed-by-the-chinese-government-and-the-chinese-communist-party-to-the-economic-and-national-security-of-the-united-states.

[8] Eric Rosenbaum, “1 in 5 corporations say China has stolen their IP within the last year: CNBC CFO survey,” CNBC, 1 March 2019, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/28/1-in-5-companies-say-china-stole-their-ip-within-the-last-year-cnbc.html.

[9] Jude Blanchett, “Confronting the challenge of Chinese state capitalism,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 22 January 2021, accessed 17 April 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/confronting-challenge-chinese-state-capitalism.

[10] Josh Zumbrun, “China Wields New Legal Weapon to Fight Claims of Intellectual Property Theft,” The Wall Street Journal, 26 September 2021, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-wields-new-legal-weapon-to-fight-claims-of-intellectual-property-theft-11632654001.

[11] United States report,“Findings On The Investigation Into China’s Act, Policies, And Practices Related To Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation Under Section 301 Of The Trade Act Of 1974,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2018.

[12] Josh Rogin, “NSA chief: Cybercrime constitutes the ‘greatest transfer of wealth in history,'” Foreign Policy, 9 July 2012, accessed April 17, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2012/07/09/nsa-chief-cybercrime-constitutes-the-greatest-transfer-of-wealth-in-history/.

[13] “How much does the federal government spend on Health Care?,” Tax Policy Center, accessed 17 April 2022, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-much-does-federal-government-spend-health-care#:~:text=The%20federal%20government%20spent%20nearly%20%241.2%20trillion%20on%20health%20care,medical%20care%20about%20%2480%20billion.

[14] Anthony Faiola, “Lithuania is learning the cost of standing up to China. Without E.U. backing, it may be forced to sit back down,” The Washington Post, 14 January 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/01/14/lithuania-china-foreign-minister-landsbergis/.

[15] Tod Lindberg and Peter Rough, “Opinion | Lithuania is the ‘canary’ of world order,” The Wall Street Journal, 28 December 2021, accessed 17 April 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/lithuania-is-the-canary-of-world-order-russia-china-baltic-states-putin-xi-jinping-11640726280?mod=Searchresults_pos2&page=1.

[16] Andrew Higgins, “Lithuania vs. China: A Baltic minnow defies a rising superpower,” The Economic Times, 11 October 2021, accessed 13 March 2022, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/lithuania-vs-china-a-baltic-minnow-defies-a-rising-superpower/articleshow/86690337.cms?from=mdr.

[17] Charlie Campbell, “What the saga of Jack Ma says about China under Xi Jinping,” Time, 4 January 2021, accessed 13 March 2022, https://time.com/5926062/jack-ma/; Brahma Chellaney, “China’s debt-trap diplomacy,” The Hill, 2 May 2021, accessed 13 March 2022, https://thehill.com/opinion/international/551337-chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy; Christopher Wray, “Director Wray addresses threats posed to the U.S. by China,” FBI, 1 February 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/director-wray-addresses-threats-posed-to-the-us-by-china-020122; “Opinion China bullies little Lithuania,” The Wall Street Journal, 22 December 2021, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-bullies-little-lithuania-taiwan-11640215202?mod=article_inline.

[18] Howard Shatz, “Economic Competition in the 21st Century,” Rand Corporation, 2020, accessed 11 December 2021, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4188.html#:~:text=Countries%20conduct%20economic%20competition%20beyond,industries%20are%20adopted%20more%20widely.

[19] Elisabeth Braw, “Opinion | China takes Lithuania as an economic hostage,” The Wall Street Journal, 6 January 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-takes-lithuania-as-economic-hostage-taiwan-global-supply-chain-trade-goods-beijing-11641506297.

[20] The White House, Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States, 2022, Washington, DC.

[21] “CFIUS Reform: Examining the Essential Elements: U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs,” 115th Congress, 2018, (Testimony of Sen. John Cornyn).

[22] Gavin Bade, “’We’re in an economic war:’ White House, Congress weighs new oversight of U.S. investments in China,” POLITICO, 19 February 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/02/19/china-investments-economy-us-congress-00008745.

[23] E. Napoletano, “U.S. national debt surpasses $30 trillion: What this means for you,” Forbes, 16 February 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.forbes.com/advisor/personal-finance/u-s-national-debt-surpasses-30-trillion-what-this-means-for-you/.

[24] Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, “Is the west laissez-faire about economic warfare?,” War on the Rocks, 11 March 2022, accessed 13 March 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/03/is-the-west-laissez-faire-about-economic-warfare/.

[25] Bryan Bender and Cory Bennett, “How China acquires ‘The Crown Jewels’ of U.S. technology,” POLITICO, 22 May 2018, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/05/22/china-us-tech-companies-cfius-572413.