Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any agency of the U.S. government. Assumptions made within the analysis are not a reflection of the position of any U.S. government entity.

Though the United States and China both face downward-trending populations with serious ramifications for their Gross Domestic Products (GDPs) and economic stability, the United States holds a considerable advantage through its potential to draw immigrants, particularly those from China. To capitalize on this advantage, the Biden administration must integrate long-term immigration reform, especially vis-à-vis China, into its policy strategy. One way to start is by streamlining existing processes and adding measures to its standing legislation to increase temporary and permanent visa opportunities for highly skilled workers in the future and prioritize those from China. For the United States to effectively compete with China in the long run, permanent immigration policies must be revamped to allow highly skilled workers the opportunity to stay in the United States to supplement population numbers, increase opportunities for immigrant innovation, and stabilize the U.S. labor force and economy, particularly in relation to Chinese output and population. If it can take advantage of the Chinese people’s desire to emigrate to the United States without compromising national security, the United States will land a twofold blow—both enhancing its own capacity base and detracting from China’s talent reserves, gaining an advantage in the strategic competition.

Setting the Stage: U.S. – China Strategic Competition

In former President Donald Trump’s U.S. Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific, his national security team identified China as a critical threat and asserted that a whole-of-government approach, specifically through promoting U.S. values abroad, maintaining the United States’ industrial advantage, and enhancing engagement and diplomatic efforts, is the best way to combat China and maintain U.S. strategic primacy in the Indo-Pacific region.[1] Though he was vehemently critical of the Trump administration’s approach, then-Presidential candidate Joe Biden, in an early-2020 article, also argued the United States must sharpen its innovative edge, strengthen its economic capabilities, and reinforce diplomatic efforts abroad to win the competition with China.[2] Rather than reinventing the tools to combat Chinese influence, the Biden administration seeks to use the same tools in a different way to reinvigorate U.S. efforts to counter China.

The Biden administration has framed the U.S. conflict with China as the battle between democracy and autocracy—a point Biden has reinforced repeatedly to both domestic and international leaders during his first year in office.[3] Biden and his team, however, cannot stop at defining the conflict through the democracy versus autocracy lens. They must also take stock of the natural advantages available to the United States and China, as well as the disadvantages facing both nations. Specifically, the Biden administration should examine both nations’ population growth and labor markets. Economic growth underpins national power, and growth is upheld by population numbers and a strong labor force. By analyzing population and demographic factors, the Biden team can glean a deeper understanding of the competition between the United States and China and devise the best strategy to retain an advantage.

In the future, decreasing population growth rates will present significant challenges to both countries’ labor markets and outputs. U.S. demographic trends, however, are far more favorable than Chinese demographic trends. By paying attention to demographics and harnessing the natural advantages of U.S. pull factors, the Biden administration can play to these strengths, improve the U.S. long-term immigration strategy vis-à-vis China, and continue to successfully compete with China on a large scale.

Why Study Demographics?

Demographics are important to maintaining (1) labor markets and (2) the stability and output of a nation. Both labor markets and economic stability provide a crucial framework to the U.S.-China strategic competition as both contribute to healthy, prosperous, and predictable domestic financial institutions, as well as successful global market and trade strategies.

Demographics and the Labor Force

Population growth is at the crux of a healthy society and economy. As a nation’s population grows or shrinks, its labor force will naturally follow suit, growing and shrinking as the larger population does, as more workers are either more available or less available to participate in the workforce. Population and participation rate yield definitive projections for economic output, education, innovation, and utility.

Directly tied to population metrics, national labor force sits at the center of markets and GDP for both the United States and China. As population numbers shift in both countries, labor markets will follow suit. These changes will play a direct role in the United States’ competition with China.

In June 2021, the U.S. civilian labor force encompassed more than 161 million individuals.[4] At the end of May 2021, U.S. employment numbers demonstrated healthy growth, with jobless rates down. At the same time, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported payroll job numbers to be increasing steadily.[5]

Demographics, Population Growth, and Output

Demography is a crucial marker for domestic stability. By examining societal births, deaths, and migrations, changes in demography directly impact the wealth and overall output of a nation.[6] Demographic data also offers policy makers a window into the overall picture of the fiscal health of a nation, lending insight into the long-term sustainability of an economy. By examining changes in demography and population, natural advantages available to the United States demonstrate that long-term immigration reform can be a key factor in strengthening the United States compared to China.

Generally, increases to a nation’s labor force drive the maximum sustainable rate of economic expansion; similarly, U.S. GDP growth rates closely follow demographic trends. From 1948 to 2001, the growth of the U.S. labor force (driven by the emergence of the baby boomer generation and the entry of women into the workforce) significantly boosted GDP growth, adding about 1.7 percentage points per year to the average annual growth in potential real GDP.[7] In the same way, Chinese GDP expansion closely follows Chinese population growth and labor force trends. Excluding figures affected by COVID-19, China’s GDP growth rate percentages are slowing at a rate mirroring its decline in population growth.[8] Previously, exceptional growth in China was driven by privatization and a strong labor force coupled with a “more market-oriented system.”[9] A population that is growing at a decreasing rate, however, combined with increasingly authoritarian measures from the Chinese government is proving counter-productive to growth opportunities.

The United States’ Demographic Status

At the beginning of 2020, the United States’ population stood at just over 331 million people.[10] Fertility rates in the United States have fallen over the last decade, and the pandemic contributed to a historic low of 1.64 in 2020.[11] Declining fertility rates play a role in declining population growth rates, which fell to an estimated 0.35% in 2020.[12] Thankfully, immigration has helped pick up the slack, as immigrants make up an increasing share of the U.S. population.[13] Overall, forward-looking data shows the United States’ population will continue growing for decades to come; demographers estimate the U.S. population will be nearly 350 million by 2030 and will likely cross the 400 million mark by 2058.

Closer inspection of U.S. data demonstrates that a portion of this population growth will not be attributed to new birth rates but to an aging baby-boomer population combined with rising life expectancy. U.S. Census Bureau data shows that by 2060 the United States is projected to demographically look like Japan does today, with nearly a quarter of the total U.S. population over the age of 65. Though its population is growing older, the United States is still projected to have a comparatively younger population than many economically similar nations, including France, Canada, Japan, and Spain.[14]

A comparatively younger population will yield tangible benefits for the U.S. economy compared to those around the world. While other nations’ declining population numbers point to smaller workforces, less labor, stagnating GDP, and challenging economic forecasts, the United States’ labor force will likely hold steady, giving output and the economy the chance to continue growing.

Significantly for both the United States and China, GDP growth is not dependent on labor alone: technology and innovation also play a crucial role. Innovation leads to higher productivity so that a stagnant or shrinking labor force yields a larger output.[15] Technological advancements are largely driven by a market economy and idea sharing among a larger population; so to promote sustained economic growth, a growing population is not the only necessity. It is also crucial to improve opportunities for innovation and production—opportunities the U.S. culture cultivates.

While the United States and most highly advanced economies are confronting population aging, pull-factors in the United States make its economy less likely to struggle in the coming years—unlike the Chinese economy. In fact, data demonstrates the United States is gaining skilled workers at the expense of China; if the Biden administration capitalizes on the increasing emigration of China’s highly skilled population to the United States, the United States can kill two birds with one stone. By strengthening the U.S. economy and talent pool, and draining China of the workers it needs most, the United States will have its best advantage to win in strategic competition with China.

China’s Demographic Status

The population of China, according to census data from December 2021, currently sits at 1.41 billion citizens—over four times the U.S. population.[16] Fertility rates on average have fallen in recent years, and the pandemic exacerbated this trend in China as elsewhere; in 2020, the Chinese population marked only 12 million births with a fertility rate of 1.69 children per Chinese woman.[17] This is the lowest fertility rate China has seen since 1961, when widespread famine swept the country, killing millions.[18] As in the United States, low fertility rates contribute to rapidly declining population growth rates; in 2020, the growth rate in China was 0.15%.[19] However, while population growth rates in both the United States and China are on the decline, data from the International Data Base projects that China is entering an era of negative population growth.[20] From 2030 on, the Chinese population will begin to decrease, and by 2065, the population is projected to fall to 1.2. billion citizens—roughly equivalent to the population size in 1990.[21]

Recognizing this impending population crisis, the Chinese government amended its former “one-child policy” in 2021 to raise the number of births, allowing three children per family. This adds to the previously implemented increase, which allowed two children per family in 2015.Lifting the policy, however, has not yielded the birth-rate increase the government hoped. In fact, the opposite has occurred. Births did rise in 2016, the first year after the policy was lifted, but have decreased every year since. Experts see the legacy of the one-child policy, which was in place for more than 30 years in China, as having created an inexorable mindset in the Chinese population. Families do not feel equipped to care for more than one child, let alone three.[22] In addition to, and perhaps because of, this decreasing birth rate, China faces a growing cohort of Chinese women putting off marriage, with marriage rates in China steadily declining since 2014 and divorce rates systematically increasing since 2003 (though this trend is demonstrating a dramatic reversal due to a new Chinese Civil Code, mandating a 30-day “cooling-off” period between a couple’s filing for divorce and approval).[23]

As the Chinese economy experiences growing prosperity, life expectancy for Chinese citizens is rising, resulting in fewer workers per Chinese retiree. Data from the United Nations Populations Division in 2019 shows that the percentage of Chinese workers as a total amount of the population will continue to decrease until 2100, whereas the percentage of workers over the age of 64 will increase until they account for nearly 30% of the entire population. Not only will China’s population begin to decrease, but it will also trend older at a faster rate in the coming decades, with direct economic impacts.[24]

As the Chinese population growth rate decreases, the number of working-age adults in the labor force is anticipated to drop by 35 million individuals over the next five years, according to the Chinese government, because of the retirement of 40 million Chinese citizens.[25] The decrease in labor force will lower the growth ceiling on the Chinese economy.

China’s labor force is particularly disadvantaged compared to that of the United States: while the United States has multiple positive pull factors driving immigration and supplementing a decreased labor force, China does not share the same possibilities. Rather than expanding the population and labor force through immigration, it seems more likely China will lose additional citizens to emigration. As the Chinese population growth decreases without the ability to supplement the numbers through immigration, the labor force will also decrease, negatively affecting China’s GDP.

The U.S. Immigration Opportunity

One answer to the U.S. labor force issue is to increase the number of immigrants legally allowed to move to the United States through changing long-term immigration mechanisms. Increasing immigration numbers will supplement U.S. diminishing birthrate numbers, sustain the labor force, and maintain or grow annual GDP. If the United States maintains yearly GDP while the Chinese economy slows, the difference will provide vital fiscal, trade, and economic advantages the United States will need to win the strategic competition with China.

The United States Already Has an Advantage in Immigration

Looking forward, net birth rates and GDP growth in both the United States and China are projected to continue decreasing, with a new side-effect—large-scale population aging in both countries.[26] The United States, however, has one critical advantage over China—national conditions that promote healthy immigration numbers and more opportunities to foster innovation. Defying earlier projections by nearly nine years, 2021 became the first year in which net international immigration overtook natural increase as the largest driver of population growth in the United States.[27] By 2050, if past trends about births, deaths, and migrations continue, immigration will constitute nearly 75% of population growth.[28]

China, on the other hand, is much further behind the United States when it comes to immigration. In 2021, the CIA Factbook estimated that China’s immigrant population is decreasing at a rate of one immigrant for every 2,000 members of the population.[29] While recent initiatives from the Chinese government are designed to attract high-income foreign nationals to permanently relocate to China, the Chinese government’s past immigration policies and records make it difficult to win public favor for new protocols.[30] For example, former messaging from the government and Chinese President Xi Jinping argued against immigration based on the principles of Chinese exceptionalism and nationalism. As a result, the Hong Kong-based digital newspaper The Initium notes many Chinese citizens now do not want China to become an immigrant country and believe that more foreigners will taint the country’s culture and political system.[31] While new immigration policies are China’s best hope to sustain population numbers, national opinion is slow to change and accept the necessary reforms to make the nation successful. While the United States faces its own unique immigration challenges, Chinese sentiment toward immigration is much less receptive.[32]

Not only does China face an already severe disadvantage in immigration because of its nationalistic messaging, but it also faces a more unexpected consequence of its authoritarian regime—emigration to the United States. Nearly 2.5 million Chinese immigrants resided in the United States in 2018, which comprised the third largest foreign-born population in the country. Further, China was the top-sending country of immigrants to the United States in 2018, replacing Mexico.[33] If China wishes to compete with the United States, it must develop policies that both remedy its immigration issues while at the same time incentivizing its citizens to remain in China rather than moving to the United States. The similar population challenges facing both the United States and China, combined with Chinese reluctance toward immigration reform, present the Biden administration with a unique opportunity. With the Chinese government crippled by its publicly facing negative opinions toward immigrants, now is the best time for the Biden administration to continue pushing immigration reform to the top of the policy agenda, before the Chinese government can sway its citizens’ opinions in the future.

Current Immigration Policies

On the Biden administration’s first day in office, House Democrats introduced the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, the most sweeping reform of the immigration system since the 2013 Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act. Among other things, this proposed bill exempts certain groups of foreign-born workers from annual caps, adds back unused visas from prior cycles, and increases other visa categories. It would significantly impact short-term immigration to the United States; however, considering the projection that the U.S. population growth will depend more on immigration than domestic births, this reform is not enough. The temporary employment-based visa system is still in urgent need of restructuring. In the long-run, immigrants will serve as the engine of the U.S. population and economy, but the hallmark immigration bill put forth during Biden’s first year in office simply does not address the long-term immigration reform currently needed.[34]

The House Democrats’ bill would increase overall visa caps in employment-based visa categories, but it does not make provisions for new visas for temporary or permanent highly skilled workers—or even make any reforms to these visa programs at all. Without permanent changes to the long-term immigration system, the Biden administration and Congress are missing an opportunity to affect widespread change in the future and are only putting a bandage on a long-term wound.

Immigration Reforms Necessary

Through executive orders and proclamations, the Biden administration is setting the stage for wide-sweeping immigration reform as a policy priority. Most of the administration’s immigration reform policies are focused, however, on near-term refugee admittance, border security reform, and climate-change challenges. These policies are near-sighted and do not consider strategic implications or account for the immense opportunity present to leverage the United States’ immigration advantages.[35] The administration should take the conversation one step further to specifically target Chinese citizens. By enhancing Chinese-specific policies and messaging, the Biden administration could both position the United States for future success and potentially cripple the Chinese economy. The United States needs to increase visa opportunities for highly skilled workers, and it should prioritize those from China. The United States may combine this policy change with strategies to specifically attract Chinese talent, either through larger visa caps, expedited processes for highly skilled workers from China looking to emigrate to the United States, or extending work programs for Chinese students studying at U.S. universities. This long-term visa reform will (1) supplement population numbers, (2) stabilize the U.S. economy, and (3) increase innovation and take away talent away from China. U.S. visa reforms will weaken China in these areas, helping the United States win the strategic competition.

The United States historically has the higher number of immigrants than any other country in the world, and, in 2020, 13.7% of the entire U.S. population was foreign-born.[36] The total number of immigrants residing in the United States sat at 44.9 million individuals in 2015. Nearly one-million new immigrants arrive to the United States annually, and it is projected that immigrant populations and their children will make up 88% of the population growth in the United States up through 2065, as long as the United States maintains its immigration trends.[37]

China, on the other hand, does not enjoy the same strong immigration numbers as the United States. In 2015, the total number of foreign-born individuals in China sat at one million individuals, a small fraction of the total Chinese population—1.41 billion individuals in 2020.[38] In addition, immigration rates to China do not demonstrate significant growth, with the net migration sitting at -0.23 migrants / 1,000 members of the Chinese population. Of those immigrants, only 38.6% were female, indicating the Chinese population will likely not be greatly supplemented by foreign-born residents.[39] Given these statistics, the United States demonstrates a substantial advantage over China in the immigration and visa arena, pointing to primacy in the strategic competition.

Each foreign-born resident residing in the United States directly impacts the U.S. economy, GDP, and overall stability. The country of origin of the highest number of new immigrants entering the United States annually is China, with 149,000 Chinese citizens immigrating to the United States in 2018.[40] Of the immigrant populations coming to the United States, the individuals from either East or Southeast Asia are among the likeliest to have higher education, with 66% having completed some college.

Visa reform, specifically visa reform targeted at generally well-educated Chinese immigrants, could prove valuable to achieve U.S. economic stabilization for years to come. With eased visa restrictions, more individuals with qualifications will be able to immigrate into the United States, supplementing the U.S. labor force and ensuring consistent economic output and GDP capabilities. On the flip side, by attracting Chinese citizens, the United States can dent Chinese talent pools and decrease Chinese innovation reserves, thereby significantly weakening the Chinese economy and strengthening the U.S. strategic position vis-à-vis China.

Visa reform is a vital component to increasing U.S. innovation, entrepreneurship, and global trade. Innovation in the United States and nations around the world is largely driven by immigrants, and encouraging greater numbers of skilled immigrants can ensure the United States will stay at the cutting edge of technology and processes that work. Migrant entrepreneurs generally drive innovation regardless of economic development level or social standing; in addition, migrants are more likely to sell products to international customers, increasing global trade ties.

The United States will gain an international upper hand in innovation through visa reform, both easing immigration processes and attracting more international talent. Meanwhile, China’s immigration numbers do not bode well for enabling creativity and entrepreneurship from foreign-born residents. If the United States can attract top Chinese talent, it could reap a double harvest—snagging top Chinese talent from Chinese companies and stalling Chinese economic growth, while utilizing that same talent to build U.S. innovation, companies, and GDP growth.

Through increasing population numbers and shoring up the U.S. labor force, the United States possesses the unique opportunity to gain an upper hand in the strategic competition with China. By ensuring the U.S. economy is stable through visa reform and attracting talented immigrants, the United States will enable innovation and creativity, while simultaneously taking advantage of Chinese demographic conditions and a slowing Chinese economy to win the strategic competition.

There are a few specific changes the United States may consider when examining visa reform designed to attract immigrants, and specifically Chinese talent. A crux for the United States will be finding the best method to amend standing legislation to maximize the number of opportunities available to highly skilled workers to allow them to stay in the United States.

One possible means of attracting and keeping talent is through reforming the International Entrepreneur Program, a visa opportunity first put in place during the administration of former President Barack Obama and revitalized during the Biden administration.[41] The program currently allows entrepreneurial immigrants a maximum of five years of residency in the United States, but it does not outline a track to permanent residency status. The Biden administration may look at reforming this program to attract top talent by promising lifelong benefits in the United States and pull talent from competitor countries, particularly China.

A separate visa reform gaining traction for legislative approval is the Heartland Visa, a proposed visa reform program designed to revitalize communities across the American Midwest. These visas could draw highly skilled immigrants to stagnating U.S. communities, providing growth and entrepreneurial opportunities for foreign-born individuals and unlocking growth potential.[42] The Heartland Visa remains a viable reform option to jumpstart U.S. economic growth while attracting top international talent to the United States. Other visa reform initiatives should include merely accelerating and simplifying visa and green card processes for highly skilled workers. These advancements can be messaged globally upon completion, including to groups of Chinese citizens abroad to encourage their emigration to the United States.

Safeguarding National Security

The United States remains a target of undisguised Chinese espionage. However, these espionage threats are not a reason to forego visa reforms that may give the United States an advantage in the strategic competition. Rather, while revamping immigration processes and visa opportunities to attract Chinese emigrants, it will be imperative that the United States observe proper national security protocols to safeguard against the threat of espionage, particularly from China. Giving credence to this threat, Chris Wray, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), recently called the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) espionage activities “more brazen” than ever, saying “there’s…no country that present a broader threat to our ideas, innovation, and economic security than China.”[43] Considering the increased threat posed by larger numbers of Chinese citizens emigrating to the United States, it is crucial that the United States approach visa reform by growing counter-espionage programs already in place and examining effective counter-espionage programs, while upholding the rights of Chinese emigrants.

Espionage, especially from China, is not a new issue, and there are a growing number of effective counter measures to effectively deal with the threat in healthy, humane ways, without pushing away talent the United States needs to effectively compete. According to the FBI, the Chinese government primarily uses economic, cyber, and technological espionage, and a whole-of-government approach is necessary to counter the Chinese espionage threat.

As one of the United States’ most effective combatants against Chinese espionage, the FBI is specifically targeting these Chinese espionage mechanisms through new programs and monitoring. For example, by sharing intelligence with international partners to discover Chinese threats and defend against espionage plots, the United States can better defend against international schemes. Additional mechanisms include new Cyber Task Forces and Counterintelligence Task Forces in every FBI field office, supported by a National Counterintelligence Task Force, designed to fight back against Chinese government hackers and cyber espionage.[44]

In addition, legislation introduced in 2021 by Senators Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz proposes healthy reform to the visa award process for Chinese citizens.[45] The proposed legislation prohibits known Chinese spies from immediately reapplying for visas and makes known espionage activities disqualifications for future visa applications. In addition, it renders family members of Chinese emigrants involved in espionage inadmissible to the United States for five years, curbing threats from known acts of espionage and better safeguarding U.S. targets. While not current law, proposals like the Protecting America from Spies Act provide actionable options for the United States.

The threat of espionage from China is not a reason to forego the immigration and visa reform the United States needs to effectively compete with China. It should be seen as an opportunity to reform counter-espionage practices and weaken Chinese aggression.

Conclusion

The Biden administration has the opportunity, by capitalizing on the United States’ natural immigration advantages alongside China’s immigration disadvantages, to gain the upper hand over China and move closer to winning the U.S.-China competition. To make the most of these advantages, smart, long-term ramifications must be considered when undertaking immigration reform. As the U.S. output and population remain stable, now is the time to undertake reform and ensure U.S. prosperity and competitiveness for generations to come.

Emily Hardman Rodgers currently serves as a contracted Program Specialist with the Office of Foreign Assistance (F) Policy Directorate at the U.S. Department of State. She previously worked as Special Assistant in the Office of the Chief Executive Officer at the Millennium Challenge Corporation. Emily was a fellow in the 2020-2021 Security and Strategy Seminar China track and is currently a fellow in the 2021-2022 Security and Strategy Seminar Iran track.

_________________

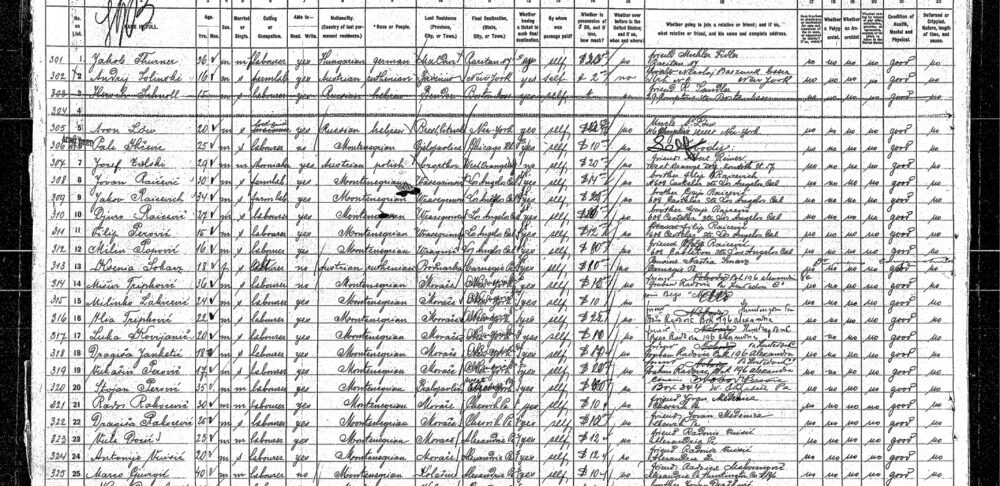

Image: Sheet of alien passengers for US Immigration arrival at NY the February 01 1906, from US Immigration Service. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alien_passengers_for_US_immigration.gif, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] National Security Council, “U.S. Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific,” White House Archives, declassified on 5 January 2021, 6-8, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/IPS-Final-Declass.pdf.

[2] Joseph R. Biden, Jr., ”Why America Must Lead Again,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again.

[3] Alex Ward, “Joe Biden wants to prove democracy works – before it’s too late,” Vox, 28 April 2021, https://www.vox.com/2021/4/28/22408735/joe-biden-congress-speech-democracy-autocracy; Jonathan Ponciano, “Biden: G-7 Countries In A ‘Contest’ To See Whether Democracies Can Compete With Autocracies Like China,” Forbes, 13 June 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanponciano/2021/06/13/biden-g-7-countries-in-a-contest-to-see-whether-democracies-can-compete-with-autocrats-like-china/?sh=446cff7493ff.

[4] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Civilian Labor Force Level [CLF16OV],” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed 5 July 2021, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CLF16OV.

[5] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “News Release,” U.S. Department of Labor, 2 July 2021, 1-2, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

[6] Demography Unit, Department of Sociology, “What is Demography?” Stockholm University definitions, accessed 27 June 2021, https://www.suda.su.se/education/what-is-demography.

[7] Mary Daly and Tali Regev, “Labor Force Participation and the Prospects for U.S. Growth,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, 2007-33, 2 November 2007, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2007/november/labor-force-participation-us-growth/.

[8] C. Textor, “Gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in China 2010-2026,” Statista, 12 April 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/263616/gross-domestic-product-gdp-growth-rate-in-china/.

[9] Bill Conerly, ”China’s Economic Miracle Is Ending,” Forbes, 4 May 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/billconerly/2021/05/04/chinas-economic-miracle-is-ending/?sh=77d58a8aa9d3.

[10] Dudley L. Poston, ”3 ways that the U.S. population will change over the next decade,” PBS News Hour, 2 January 2020, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/3-ways-that-the-u-s-population-will-change-over-the-next-decade.

[11] Janet Adamy and Anthony DeBarros, “COVID-19 Pandemic Led to Smaller-Than-Expected Baby Bust, Data Suggests,” Wall Street Journal, 8 February 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/covid-19-pandemic-led-to-smaller-than-expected-baby-bust-new-data-suggest-11644328800#:~:text=Despite%20the%20small,in%20the%201930s.

[12] Aaron O’Neill, “United States: Population growth from 2010 to 2000,” Statista, 2 February 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/269940/population-growth-in-the-usa/.

[13] Miriam Jordan and Robert Gebeloff, “Amid Slowdown, Immigration is Driving Population Growth,” New York Times, 5 February 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/05/us/immigration-census-population.html.

[14] Jonathan Vespa, Lauren Medina, and David M. Armstrong, “Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060,” United States Census Bureau, revised 2 February 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf.

[15] Daly and Regev, “Labor Force Participation.”

[16] “International Data Base (IDB) China,” United States Census Bureau, accessed 1 July 2021, https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?YR_ANIM=2035&menu=countryViz&FIPS_SINGLE=CH&COUNTRY_YEAR=2021.

[17] C. Textor, “Number of births per year in China from 2011 to 2021,” Statista, 17 January 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/250650/number-of-births-in-china/; Aaron O’Neill, “Total fertility rate in China from 1930 to 2020,” Statista, 2 March 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1033738/fertility-rate-china-1930-2020/.

[18] Steven Lee Myers, Jin Wu, and Claire Fu, “China’s Looming Crisis: A Shrinking Population,” New York Times, 17 January 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/01/17/world/asia/china-population-crisis.html.

[19] C. Textor, “Population growth in China from 2000 to 2021,” Statista, 17 January 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/270129/population-growth-in-china/.

[20] Shi Xiaoli, “Population and Labor Green Paper: China Population and Labor Issue Report No. 19 released,’” China Social Science Net, 4 January 2019, http://ex.cssn.cn/zx/bwyc/201901/t20190104_4806519_1.shtml.

[21] “International Data Base (IDB) China.”; Xiaoli, “Population and Labor Green Paper.”

[22] Liyan Qi, ”China’s New Three-Child Policy: What You Need to Know,” Wall Street Journal, 31 May 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-new-three-child-policy-what-you-need-to-know-11622471685.

[23] Elsie Chen and Sui-Lee Wee, “China Tried to Slow Divorces by Making Couples Wait. Instead, They Rushed,” New York Times, 26 February 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/26/business/china-slowing-divorces.html; Frida Lindberg, “China’s Drastic Drop in Divorce Rates,” Institute for Security and Development Policy, 9 June 2021, https://isdp.eu/china-drastic-drop-divorce-rates/.

[24] Myers et al., “China’s Looming Crisis: A Shrinking Population.”

[25] Frank Tang, “China population: workforce to drop by 35 million over next five years as demographic pressures grow,” South China Morning Post, 1 July 2021, https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3139470/china-population-workforce-drop-35-million-over-next-five.

[26] William H. Frey, “What the 2020 census will reveal about America: Stagnating growth, an aging population, and youthful diversity,” Brookings Institution, 11 January 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/research/what-the-2020-census-will-reveal-about-america-stagnating-growth-an-aging-population-and-youthful-diversity/; Charlie Campbell, “China’s Aging Population Is a Major Threat to Its Future,” Time, 7 February 2019, https://time.com/5523805/china-aging-population-working-age/.

[27] Jordan and Gebeloff, “Amid Slowdown, Immigration is Driving U.S. Population Growth.”

[28] Vespa et al., “Demographic Turning Points for the United States,” 11.

[29] “Net Migration Rate: China,” The CIA World Factbook, accessed 5 July 2021, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/net-migration-rate/.

[30] Chauncey Jung, “China’s Proposed Immigration Changes Spark Xenophobic Backlash Online,” The Diplomat, 5 March 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/chinas-proposed-immigration-changes-spark-xenophobic-backlash-online/.

[31] Tan Enru, “Chinese netizens are boycotting foreigners’ permanent residency legislation,” The Initium, 1 March 2020, https://theinitium.com/article/20200301-internet-observation-foreign-permanent-residence/.

[32] Claire Felter, Danielle Renwick, and Amelia Cheatham, “The U.S. Immigration Debate,” Council on Foreign Relations, 31 August 2021, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-immigration-debate-0.

[33] Carlos Echeverria-Estrada and Jeanne Batalova, “Chinese Immigrants in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, 15 January 2020, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/chinese-immigrants-united-states-2018.

[34] Sadikshya Nepal, “U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021: What It Does and Does Not Do for High-Skilled Immigration Reform,” Bipartisan Policy Center, 26 February 2021, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/u-s-citizenship-act-of-2021/.

[35] “President Biden’s Executive Actions on Immigration,” Center for Migration Studies, 24 May 2021, https://cmsny.org/biden-immigration-executive-actions/.

[36] Phillip Connor and Gustavo Lopez, “5 facts about the U.S. rank in worldwide immigration,” Pew Research Center, 18 May 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/05/18/5-facts-about-the-u-s-rank-in-worldwide-migration/.

[37] Abby Budiman, “Key finding about U.S. immigrants,” Pew Research Center, 20 August 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/.

[38] “Population, total – China”, The World Bank Group, accessed November 6, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CN

[39] “China – Facts and Figures,” UN International Organization for Migration, accessed January 6, 2021, https://www.iom.int/node/29989/facts-and-figures

[40] Abby Budiman, “Key finding about U.S. immigrants,” Pew Research Center, 20 August 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/

[41] Ahmed Mady, “America needs visa reform to stay competitive,” The Hill, 17 November 2021, https://thehill.com/opinion/immigration/581970-america-needs-visa-reform-to-stay-competitive?rl=1; “International Entrepreneur Parole,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, accessed 1 January 2021, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/humanitarian-parole/international-entrepreneur-parole.

[42] Adam Ozimek, Kenan Fikri, and John Lettieri, “From Managing Decline to Building the Future: Could a Heartland Visa Help Struggling Regions?” Economic Innovation Group, April 2019, https://eig.org/heartland-visa.

[43] Christopher Wray, “China’s Quest for Economic, Political Domination Threatens America’s Security,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1 February 2022, https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/director-wray-addresses-threats-posed-to-the-us-by-china-020122.

[44] Christopher Wray, “China’s Quest for Economic, Political Domination Threatens America’s Security.”

[45] Senator Ted Cruz, “Protecting America from Spies Act,” 117th Congress, 1st Session, 20 May 2021, https://www.rubio.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/e7ffe24c-0bae-4119-a252-6ebe6ac836c6/973F62422C3E0182013B6FC674721355.protecting-america-from-spies-act-1-.pdf.