Review of Revolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of Law by Bruce Ackerman (Harvard, 2019).

Nevertheless, the past is over and it is the future that beckons to us now. That future is not one of ease or resting but of incessant striving so that we may fulfil the pledges we have so often taken and the one we shall take today.”

-Jawaharlal Nehru [1]

Nehru’s words aptly epitomize the awesome task of constitutionalization before the Indian Constituent Assembly in 1947, as well as for numerous other revolutionary movements around the world. The drafting and ratification of a constitution provides not only a basic set of rules to guide tomorrow’s leaders but also define a nation’s substantive commitments looking far into the future. In his book Revolutionary Constitutions, Yale Law Professor Bruce Ackerman traces the history of various countries that attempted the formidable feat of constitutionalization.

He theorizes three different pathways through which the legitimation of constitutionalism occurs: revolutionary outsiders, responsible insiders, and elite construction. It is this first ideal type upon which Ackerman focuses his inquiry. Tracing the “constitutionalization of revolutionary charisma,” Ackerman periodizes the constitutional development of nine countries, including India, South Africa, and Poland, that followed the revolutionary pathway. In this review, I argue that Ackerman’s theory provides a useful analytic framework for understanding the budding constitutionalism of Tunisia, with the role of two charismatic leaders adding a unique twist to the collapse-hegemonic paradigm set by India.

Ackerman’s Lifecycle of Charisma

Professor Ackerman conceptualizes a four-time model common to all of the revolutionary constitutional movements that he surveys. During Time 1, revolutionary outsiders lead a mobilized insurgency and launch an attack upon the legitimacy of the existing regime. [2] Through the conversion of their protest movement into a movement party, the leaders of the insurgent movement translate the high-energy politics into a constitution at Time 2, as exemplified by Nehru’s self-conscious move to transfer the revolutionary authority earned by his Congress Party to the Constituent Assembly.

Expressly distinguishing Nehru from leaders like Stalin and Mao, who both attempted revolutions of a “totalizing” nature, Ackerman focuses his inquiry upon those charismatic revolutionaries who envisioned their movements “on a human scale.” In practice, this meant targeting the political and social spheres most in need of reform and then constitutionalizing these revolutionary reforms. [3]

The success of this constitutional project inevitably leads to a Time 3, where movement leaders pass from the scene and are replaced by less charismatic successors-creating a legitimacy vacuum and a chain of succession crises that prompt the judiciary to increasingly assert their constitutional authority. This culminates in Time 4, where the high court successfully establishes its supremacy and legitimates its role as the ultimate defender of the revolutionary constitution.

Tunisia: An Ackerman Case Study

The North African nation of Tunisia fits well within this four-time framework. Before the collapse of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s government during the Freedom and Dignity Revolution of 2011, also known as the Jasmine Revolution, Tunisia had seen only two presidents and little serious multi-party competition in the five decades since winning independence from France. [4] To understand the unique political relationship between union bosses and Ben Ali’s party, the Rassemblement Constitutionnel Démocratique (RCD), Beatrice Hibou describes two of the most powerful labor unions in Tunisia-the Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (UGTT) and Union Tunisienne de l’Industrie, du Commerce et de l’Artisanat (UTICA)-as mere “appendage[s] of the apparatus of party power.” [5] This dynamic underscores the preeminently political role that unions play in Tunisian politics, as well as the extent to which Ben Ali controlled the Tunisian political and economic spheres. Nevertheless, his two decades of rule were hardly perfect, marked by internal unrest over increased unemployment and corruption. [6] After the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi on December 17, 2010, burgeoning nationwide protests forced the resignation of President Ben Ali. His sudden downfall began a brief yet crucial period of revolution during Tunisia’s Time 1, akin to that caused by the exit of Lord Mountbatten in India. [7]

The collapse of Ben Ali’s RCD party made way for the transition from protest movement to movement party. While Ben Ali’s deputies assumed power in the resulting interim government, there was little that Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi and interim President Fouad Mebazaa could do to appease the protesters. Their main attempt came with appointing a new unity government that included opposition members; however, the inclusion of sitting ministers from the disgraced Ben Ali government sparked not only the resignation of the opposition members but also more protests decrying the illegitimacy of the new government. [8] Although both leaders resigned from the RCD and suspended the party as a gesture of coming reforms, Ghannouchi ultimately resigned, and Mebazaa named Beji Caid-Essebsi as Ghannouchi’s replacement for prime minister. Like the collapse of the British imperial regime in India, Ben Ali’s flight to Saudi Arabia left a political vacuum that previously banned parties and exiled leaders sought to fill.

Two prominent leaders in particular, Moncef Marzouki of the Congrès pour la République (CPR) and Rached Ghannouchi of the Ennahda movement, immediately declared their return to Tunisia from their respective exiles in France and Britain. [9] Public support for their returns was unparalleled; an estimated 10,000 men and women greeted Rached Ghannouchi upon his arrival in the Tunis airport after twenty-two years in exile. [10] In the ensuing months, as Essebsi guided the country to its first multi-party election in October 2011, Ennahda spared no time in re-establishing its organizational structure, which had been secretly sustained by Abdelhamid Jlassi during its time underground, and developed a significant advantage over its secular counterparts. [11] Similar to the organizational dominance of the Indian Congress Party in 1938, Ennahda had set itself up for a similarly authoritative role in the constitutionalization of Tunisia – with Ghannouchi as the Nehru of the Arab Spring.

As each party competed for a seat at the constitutional bargaining table, the election of a Constituent Assembly began the race against time to draft a constitution. With 70 percent of the population turning out for the October 2011 elections for the Constituent Assembly, the Ennahda Party won 40 percent of the vote and 88 of the 217 seats in the body. [12] Despite Ennahda’s Islamist background, Ghannouchi soon demonstrated his party’s commitment to moderation and pragmatism, forming the Troika coalition with the CPR, Marzouki’s party, and Ettakatol (FDTL).[13] Ghannouchi named Marzouki the Assembly’s president to oversee the transition, while another Ennahda official served as interim Prime Minister.

Though leftist activists, like Zied Ben Abdeljelil, challenged Ennahda’s legitimacy by claiming the party was never at the forefront of the uprising, many others maintained that true legitimacy – the ultimate vindication of charismatic authority – came at the ballot box. [14] Accordingly, Safwan Masri notes that the parties which “fared best among Tunisians were those that had no ties with Ben Ali and could claim a history of resistance to his authoritative regime.” [15] Who could be further from Ben Ali’s regime than the founders of the banned Ennahda and CPR parties, Ghannouchi and Marzouki?

From the very beginning, religious tensions between Ennahda and the secular parties dominated the constitutional drafting process. The very nature of the pluralistic Troika placed Ennahda in the crosshairs of hardline Salafists, who opposed both its coalition government with two secular parties and the principles of secularism in the new constitution.[16] Simultaneously, secularists pushed for the removal of Islamic norms, whether explicitly or implicitly, in the constitution. To reinforce the bargaining power that labor unions had in the complex constitutional negotiations, the UGTT threatened a strike that would paralyze the country.[17] Such tensions were not aided when the Salafi movement group Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) assassinated leftist opposition parliamentarian Chokri Belaid on February 6, 2013, as well as opposition leader Mohamed Brahmi in July. [18]

After the UGTT carried out a two-day strike that involved an estimated 50 percent of all unionized workers, Ghannouchi and Marzouki made significant concessions to secularists. Working alongside three other associations as part of the National Dialogue Quartet, the UGTT brokered a series of compromises to salvage the constitution in 2014 (for which the Quartet received the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize)-including one requiring the resignation of the Troika coalition and its replacement by a caretaker government. [19] It is important to note that the Troika could have maintained its grip on power and called for new elections, like Lech Wałęsa did in 1990 while sabotaging any chance of reaching a compromise constitution. However, its voluntary sacrifice of power for a lasting constitution at Time 2 demonstrated Ennahda’s commitment to a revolution “on a human scale.” [20] In doing so, the Troika locked in its structural gains without pushing the already tenuous constitutional order beyond its breaking point.

Putting a Price Tag on Charisma

At this point in history, Ackerman provides a near-perfect fit for the constitutional development of Tunisia’s trip down the revolutionary pathway. Nonetheless, Ghannouchi and Marzouki’s steadfast alliance raises interesting questions for Ackerman’s central thesis, as it seems that each leader wielded his fair share of revolutionary charisma. To what extent can revolutionary charisma be shared or even measured, and what effect does this have upon successors’ ability to fill the legitimacy gap left by charismatic leaders? This partnership (or potential rivalry) seems unparalleled by the other revolutions Ackerman considers, with Mandela, De Gasperi, de Gaulle, and Wałęsa recognizing their roles at the center of their own movements.

In fact, Ghannouchi and Marzouki could be more aptly compared to Nehru and Gandhi, had Gandhi not “divorc[ed] himself from the next generation’s effort to gain democratic control of the commanding heights.” [21] All things considered, it makes sense to view the Troika more as an analogue of the hegemonic Indian Congress Party or the African National Congress than the fragmented party systems of Italy and France, as the Tunisian coalition government led decisively with Ennahda at the helm. Perhaps this comparison is only fair; Marzouki had visited India in his youth to study Gandhi’s protest methods and later travelled to South Africa to observe its transition from apartheid. [22] Moreover, the sudden departure of Ben Ali further underscores the similarities between Tunisia and the collapse-hegemonic revolutionary path blazed by India.

Though it is concerning that only one of the 12 seats on the Constitutional Court has been filled, complicating the judiciary’s ability to assert its supremacy, it is still early. [23] So long as Ghannouchi maintains his powerful presence on the political scene as the Speaker for the Assembly of the Representatives of the People, Tunisia remains firmly in Time 2, with the rest of the Arab world closely watching the fate of its democratic experiment.

Kevin Xiao is an Officer for the AHS Chapter at Yale University, where he is majoring in political science.

—

Notes:

[1] Bruce A. Ackerman, Revolutionary Constitutions: Charismatic Leadership and the Rule of Law (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019), 61.

[2] Ackerman, 4.

[3] Ackerman, 29.

[4] Laurel Miller et al., Democratization in the Arab World: Prospects and Lessons from Around the Globe, RAND Corporation Monograph Series, (Santa Monica: RAND, 2012), 58.

[5] Beatrice Hibou, The Force of Obedience (Cambridge: Polity, 2011), 128.

[6][6] Nur Köprülü, “The Paradox of Inclusion/Exclusion of Islamist Parties in Tunisia and Jordan after the Arab Uprisings: A Comparative Study,” Insight Turkey 22, no. 1 (2020), 215, https://doi.org/10.2307/26921176.

[7] Ackerman, 58.

[8] CNN Wire Staff, “State TV: 2 Top Officials Depart Ben Ali’s Party In Tunisia,” 18 January 2011, http://www.cnn.com/2011/WORLD/africa/01/18/tunisia.protests/index.html.

[9] Miller et al., 61.

[10] Safwan M. Masri, Tunisia: An Arab Anomaly (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 56.

[11] Sevinç Alkan Özcan, “The Role of Political Islam in Tunisia’s Democratization Process: Towards a New Pattern of Secularization?,” Insight Turkey 20, no. 1 (2018): 216.

[12] Miller et al., 61.

[13] Samuel R. Greene and Jennifer Jefferis, “Overcoming Transition Mode: An Examination of Egypt and Tunisia,” International Journal on World Peace 33, no. 4 (2016), 19.

[14] Osman El Sharnoubi, “Tunisia Opposition Fear Ennahda Power Grab,” Ahram Online, 17 January 2012, http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/2/8/31906/World/Region/Tunisia-opposition-fear-Ennahda-power-grab-.aspx.

[15] Masri, 57.

[16] Özcan, 219.

[17] Ian M. Hartshorn, “Organized Interests in Constitutional Assemblies: Egypt and Tunisia in Comparison,” Political Research Quarterly 70, no. 2 (2017), 413.

[18] Frédéric Volpi and James M. Jasper, eds., Microfoundations of the Arab Uprisings: Mapping Interactions between Regimes and Protesters, Protest and Social Movements 13 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018), 100.

[19] “The Nobel Peace Prize 2015,” NobelPrize.org, 29 February 2016, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2015/tndq/history/.

[20] Ackerman, 265.

[21] Ackerman, 58.

[22] Steve Coll, “The Casbah Coalition,” The New Yorker, 4 April 2011, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/04/04/the-casbah-coalition.

[23] Sharan Grewal, “Tunisia Needs a Constitutional Court,” Brookings Institution (blog), 20 November 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/11/20/tunisia-needs-a-constitutional-court/.

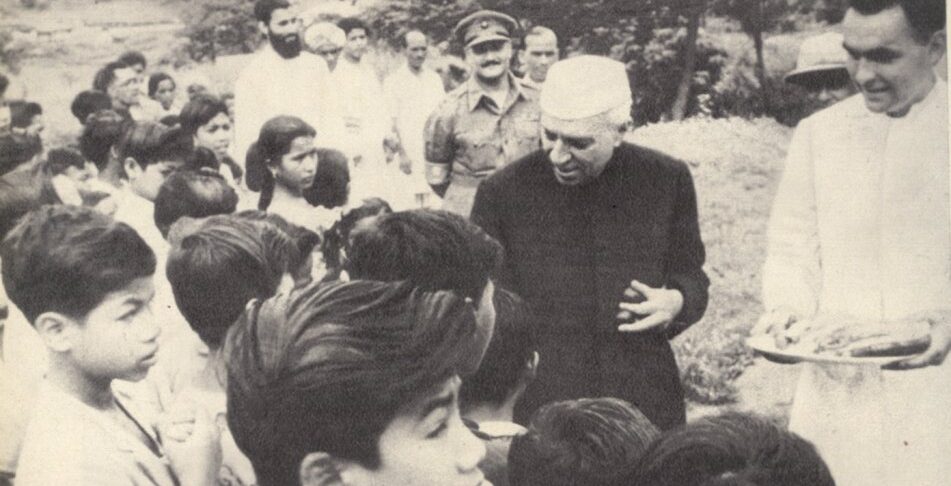

Image: “Jawaharlal Nehru hands out sweets to students at Nongpoh in Meghalayas” by ktravasso, retrieved from http://flickr.com/photo/94252507@N00/393887565, used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/).