“But what are these, a dozen missionaries… among the millions of Chinese to whom the Gospel is to be preached? And where are the converts, the churches, and the Christian families among the Chinese?… Darkness covers the land, and gross darkness the people. Idolatry, superstition, fraud, falsehood, cruelty, and oppression everywhere predominate …Though the prospect before us is dark, very dark, yet we see no reason to be discouraged; on the contrary, we find much to call forth new faith, new zeal, new efforts, new laborers, and above all, more frequent and fervent prayers.”

– Elijah Coleman Bridgman, the first American Protestant missionary to China (1835)1

Idealism has proven an enduring force shaping U.S. policy towards China, reemerging even after periods of darkness in the U.S.-China relationship. American missionaries to China in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries were among the first and most influential of the United States’ China optimists, popularizing rosy depictions of a soon-to-Westernize China back home. These images of China would endure even as missionary activity declined in the 1930s-1940s. American missionaries’ optimism for China lived on among their descendants, both biological and intellectual, who went on to fill the ranks of elite institutions shaping the United States’ China policy. The 1949 establishment of the People’s Republic of China shattered Americans’ optimism for China, leaving the nation bewildered why things had gone so wrong with China. Yet Americans’ idealism for China would soon return.

The 1949 debate over who “lost China” to communism parallels the contemporary conversation about how the United States has again “gotten China wrong.” To understand how misguided idealism may have led U.S. policy towards China awry in recent decades—and how it might again in the future—this paper revisits how the United States’ undue idealism for China first developed. To do so, this paper explores the origins, influence, and conditions underlying the optimism of the United States’ early China idealists: Protestant missionaries.

The paper is broken down into four sections:

1) The origins of American optimism for China: the United States’ early Protestant missionaries;

2) A uniquely American phenomenon: Why American missionaries were particularly susceptible to optimism for China;

3) The enduring influence of the United States’ early China missionaries: The power of family biography and the cases of Pearl Buck and Henry Luce;

4) Key lessons: Assessing the conditions that fostered missionaries’ undue optimism for China.

The Origins of American Optimism for China: America’s Early Protestant Missionaries

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, American missionaries in China shaped the United States’ early perceptions of China as a quixotic but uncivilized nation that needed the United States. American missionaries—overwhelmingly Protestant—came to China several decades after the American Revolution, following in the footsteps of American merchants. These early missionaries came not only to preach but also to teach, provide healthcare, and build vital infrastructure. The first American missionary, Elijah Coleman Bridgman, arrived in China in 1829; the following year, the Baptist South China Mission was established and an additional five American missionaries left for China.2 The number of American missionaries would grow throughout the century, but remained limited: by 1905, there were only 1,300 Protestant missionaries for a population of 400,000,000.3 Merchants and missionaries were concentrated in Western enclaves along China’s eastern coasts, residing in the treaty ports established by the unequal treaties of the Opium Wars. From the very beginning, the Christianization of China was not the only goal of American missionaries: one report by American missionaries outlined American Christians’ responsibilities as “not simply introducing new ideas into the country but modifying its industrial, social and political life and institutions.”4

The scope of these early ambitions was incongruous with on-the-ground realities from the outset: the Christianization of China alone, much less the nation’s comprehensive Westernization, would prove enormously difficult. One reverend acknowledged that after a decade in China, “he had made, by his own reckoning, ten converts.”5 His experience was illustrative of the broader lack of success of Protestantism in China. According to one estimate, the American Protestant cause had achieved a mere 100 converts by 1860.6 Even after a century in China, missionaries’ fortunes had not much improved, as American Sinologist Owen Lattimore noted in 1932: “There can be few competent lay observers who believe that Protestant Christianity in China, if deprived of foreign funds, would not become degenerate and distorted within a few years.”7 Such progress did not dim hope: missionaries remained committed to China, often staying for decades. The reverend with ten converts would continue to proselytize in China for another two decades.8

The China described by missionaries easily took hold in Americans’ imaginations because few Americans had any other knowledge of China. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act exacerbated the gap in Americans’ knowledge, as American historian James Bradley has summarized: “The cleansing of the Chinese from America’s West [after the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act] created a vacuum in U.S.-Chinese affairs, as few Americans would ever encounter a Chinese person again.”9 American elites, including policymakers, had similarly limited understandings of China in the nineteenth century, as another American historian has explained: “There was an overall lack of interest [in China] from the very top of the U.S. diplomatic corps as the presidents and Secretaries of State were preoccupied with European and South American diplomacy. During the period of 1843 to 1861 none of the presidents with the exception of James Buchanan was well informed or interested in China.”10 This information void would provide fertile ground for the myth of a soon-to-Westernize China to take hold in American imagination and policy.

A Uniquely American Phenomenon: Why American Missionaries Were Particularly Susceptible to China Idealism

Missionaries to China were not a unique American tradition—France, Spain, Italy, and Portugal, for example, have a much deeper history of missionary exchanges with China—yet American missionaries distorted the United States’ perceptions of China to an extent that other countries’ missionaries did not. The answer to this apparent paradox lies in the differences in how American missionaries, who were overwhelmingly Protestant, and missionaries from Western European countries, who were overwhelmingly Catholic, approached proselytization in China.

Protestant missionaries, who constituted the vast majority of American missionaries in China, lived differently and kept a degree of separation from the Chinese they sought to proselytize, positioning them poorly to provide accurate depictions of on-the-ground realities in China. Owen Lattimore detailed Protestants’ isolation from the Chinese population in his 1930 book High Tartary: “Protestants…try to live humbly, by Western standards; but these very standards are so much above those of the depressed [Chinese] classes among which they work…”11 American medical missionary and later Congressman Walter Judd described similar conditions, lambasting his counterparts in a 1927 letter to a Boston-based missionary for their tendency to create a “miniature home land” and a “little America” in China.12 The twentieth-century British consular officer Eric Teichman described Protestants’ approach similarly: “The Protestant missionary…usually lives a Western life in a Western home, cut off from contact with the orientals amongst whom he is working.”13 Protestants also did not hesitate to take “extended summer holidays…abandon[ing] their work in the hot cities to retire for months on end to their hill resorts.”14

Catholic missionaries took a different approach, integrating into Chinese communities and living and dying among those they sought to proselytize, as Lattimore further described: “the Catholics almost never go on leave, and as for retiring, they usually die at their posts…”15 Teichman, reflecting on Protestants’ summer holidays, concurred, noting that Catholics “would never dream of abandoning their work in this way.”16 Catholics’ celibacy facilitated their integration, as Teichman further described: “the celibacy of the Catholics is also greatly to their advantage and enables them to merge themselves with the Chinese in a way impossible for the Protestant missionary, encumbered with family ties and a European home.”17 Catholic missionaries also tended to come to China with greater levels of training and education, perhaps further enhancing their ability to integrate with the Chinese: “On the whole there is remarkable variety in the standard of education and intellect amongst the Protestant missionaries in China; and the Catholic priests would appear to be well ahead of them in this respect.”18

Most Protestant missionaries believed proselytization would occur top-down, beginning with China’s leaders and gradually spreading to the rest of the Chinese population. Protestant missionaries therefore interpreted the rise of self-proclaimed “Christian” leaders in China as a signal that China was Christianizing—despite the premise repeatedly proving flawed. For example, American missionaries initially viewed the 1850–1864 Taiping Rebellion with great optimism because the rebellion’s leader was a self-proclaimed Christian who had studied under the auspices of a Tennessee Baptist missionary.19 Protestants would continue to view the conversion of key Chinese leaders with great—and misplaced—optimism throughout the early-twentieth century, as a historian on Chiang Kai-shek has described: “Sun Yat-sen and Feng Yü-hsiang (known as the Christian general) were the most notable examples [of high-profile Chinese Christians]. Both had been converted with little impact on the Christian movement in China.”20 Chiang Kai-shek’s 1930 conversion to Protestantism similarly inspired great optimism among American Protestants, even as on-the-ground conditions for missionaries deteriorated under Chiang’s watch and the timing of his conversion fortuitously coincided with his efforts to secure American aid following Japan’s 1931 invasion of Manchuria.21

Catholic missionaries were split on how proselytization would occur in China. Like the Protestants, the Jesuits took a top-down approach to conversion, seeking to first convert Chinese leaders. Yet the Jesuits may have been less susceptible to the optimism of their Protestant counterparts due to their close integration with the Chinese population.22 The Dominicans, meanwhile, took a bottom-up approach, believing that it was most important to first spread Catholicism among the masses.23

American Protestants were unique even among Protestant missionaries in their approach to proselytization. British Protestant missionaries often traveled under the auspices of non-sectarian organized missions that required missionaries to closely integrate with the Chinese population. Britain’s inter-denominational Protestant China Inland Mission (CIM), one of the largest missions in China, required its members to live among the Chinese in Chinese-modeled dwellings, learn the Chinese language, and even wear Chinese clothing—an approach very different from the “little Americas” that American Protestant missionaries often created.24 As a result, CIM and others like it often adopted what was essentially a Catholic approach, as Teichman further described: “It may be noted that the China Inland Mission, one of the largest and oldest and in the opinion of many still the finest and purest of all the Protestant missions established in China, originally adopted to a great extent the Catholic method of working from amongst the Chinese.”25

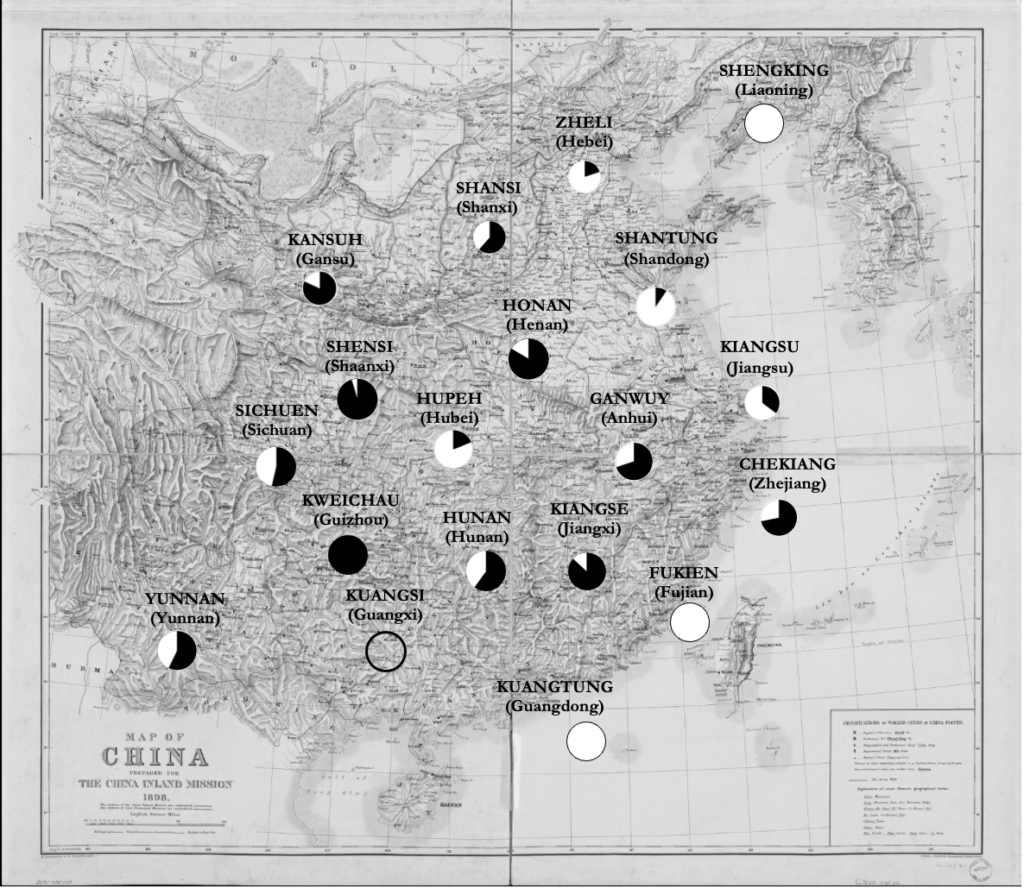

Perhaps most importantly, American Protestants and Catholics tended to work in different parts of China, leading to discrepancies in how well each organization was positioned to understand on-the-ground realities in China. Catholic missionaries, along with CIM, prioritized proselytizing in China’s inland provinces after the Qing dynasty lifted restrictions on missionary activity in 1860. Protestant missionaries, meanwhile, remained concentrated in the port cities along China’s southeastern coastline (see Figure 1). American Protestant missionaries’ disproportionate presence in China’s Westernized enclaves likely exacerbated their distorted perceptions of China, as conditions in port cities were taken as representative of those of greater China.

Figure 1: Map of China prepared for the China Inland Mission (CIM) in 1898, depicting the location of Protestant and inter-denominational CIM missions, the latter of which adopted an essentially Catholic approach in China. Black indicates the proportion of CIM missions; white indicates the proportion of Protestant missions.26

Differences in funding sources between Catholic and Protestant missionaries also led to different incentives for how each group of missionaries characterized China and their prospects for success back home. American Protestant missionaries were heavily dependent on financing from back home, as an American historian has described: “The financiers of the [Protestant] missions expected to see results and, if their expectations were not met, funds were withdrawn. It was not unusual for missionaries to change their source of financial support during the course of a mission.”27 Catholic missions, meanwhile, tended to be self-sustaining, as Lattimore described: “Like most Catholic missions, this [Catholic mission] was financed only in the minimum from outside. The expansion of the community, once begun, depended largely on its own wealth and worth.”28A nineteenth-century British author similarly summarized these differences: “The Protestant missions are supported mainly by funds from Europe and America, the Americans being especially lavish… The Roman Catholics depend more upon contributions from their converts and upon rents, etc.”29 Catholic missionaries, not reliant upon funding from their home countries, therefore lacked the same incentives to inflate their success to audiences back home.

The Enduring Influence of America’s Early Missionaries: The Power of Family Biography and the Cases of Pearl Buck and Henry Luce

Protestant missionaries’ late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century experiences in China would inform Americans’ perceptions of China throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Their descendants, often inheriting unduly romantic perceptions of China from their parents, would join Congress, the Department of State, leading businesses, key religious organizations, elite newspapers, academia, and other sectors influential on U.S. policy, providing a powerful force pushing the nation towards policies sympathetic to China. Americans, still with little other knowledge of China, would believe in the China created by missionaries and propagated by their descendants. Ongoing exchanges between American missionaries and China only reinforced this understanding. This section explores two notable cases illustrating how Protestant missionaries’ romantic views of China lived on in their descendants, many of whom would shape U.S. China policy.

Pearl Buck

Today, Pearl Buck is well-known for authoring a novel on China that would capture the imaginations of Americans and propel her to the status of one of the United States’ best-known China hands. Her 1931 novel The Good Earth, depicting the lives of ordinary Chinese peasants, had a profound effect on Americans, as American political scientist and journalist Harold Isaacs detailed in 1954: “No single book about China has had a greater impact [on Americans’ understanding of China] than her famous novel, [The Good Earth]…It can almost be said that for a whole generation of Americans she ‘created’ the Chinese.”30 The remarkable success of the novel, which earned Buck a Pulitzer Prize in 1932 and contributed to her winning a Nobel Peace Prize in 1938, made her “an assumed authority on all things Chinese,” as American historian James Bradley has described.31 With this position, she would propagate optimism for China among Americans, heralding that “[China] is at last knocking at [American] doors…seizing ideas which she thinks will be useful to her, and returning again to her own land to use her new knowledge in her own fashion.”32 Pearl Buck directly influenced not only the American public’s views on China, but also American elites’ perceptions of China. In a series of interviews in the 1950s, Isaacs interviewed 181 American elites to examine where they had developed their views on China. Of those interviewed, 69 explicitly pointed to The Good Earth and Pearl Buck without prompting.33

Buck’s influence in shaping Americans’ favorable perceptions of China is well-documented, but it is less well-known where her views developed: America’s early missionaries. Buck, born in 1892 to Caroline (Carie) and Reverend Absalom Sydenstricker—the man who succeeded in attaining ten converts in ten years—spent her childhood in southern China, first in Huai’an, then Zhenjiang, then Shanghai.34 In Huai’an, she “was confined to the house and its walled compound,” as British writer Hilary Spurling details in a biography on Buck.35 Spurling elaborates on Buck’s separation from the realities of China, noting that her “only view of anything beyond her high garden wall was the procession of feet she was short enough to see passing in the gap between the heavy wooden gate and the ground…her impression of this period afterward was of happiness and security.”36 Buck’s “China” did not exist outside of her immediate surroundings, as Buck reflected in her 1954 autobiography My Several Worlds:“I grew up in a double world, the small white clean Presbyterian American world of my parents and the big loving merry not-too-clean Chinese world, and there was no communication between them.”37 In Zhenjiang, the family first lived in run-down quarters close to the port—“magical” surroundings to Buck—but would eventually move to a Baptist compound that looked “out over green grave lands to a pagoda on the far side of the hill.”38 During the day, she went to a school established by the missionaries and played with the children of other missionaries and Chinese girls who attended school with her—“wonderful playmates” whom she “loved.”39 “Those early years,” as she would later reflect, were “the idyl of happiness.”40

Ultimately, Pearl Buck’s upbringing in a “little America” in China, the quintessential model of Protestant missionaries, led her to develop and later propagate rosy depictions of China that would prove instrumental in shaping American perceptions of the nation. Yet, her case is not unique: the Protestant approach to China would lead to undue China optimism among many Americans, including those instrumental in shaping U.S. policy.

Henry Luce

There are striking parallels between the lives of Pearl Buck and the media titan Henry Luce, an equally influential figure upon U.S. public opinion towards China in the 1930s and 1940s. Born to a Protestant missionary family in Shandong province in 1898, Henry Luce and his family lived in true Protestant fashion, primarily residing in compounds separated from the Chinese populations they sought to proselytize. Late-twentieth-century author and Protestant missionary in China B.A. Garside recounted this separation in the Luce family’s early years in China: in 1897 and 1898, the family lived “within the walled compound of the Girls’ School at Tengchow… From their rooms on the second floor they looked down on the thatched roofs of Chinese dwellings…”41

After a year-long furlough in the United States from 1906–1907, the family returned to China, settling in another compound in the city of Weihsien in Shandong province, as B.A. Garside further detailed:

[A]round the Weihsien compound ran a high, smooth wall, quite in keeping with the landscape, for the Chinese love a wall. Within, what a busy life went on! There was the College, the Boys’ School, the Girls’ School, the Hospital, the Church—all within an area of some ten acres…from the upper windows of the buildings in the compound they could look out across the great, brown plains of Shantung.42

Life in the compound differed markedly from the lives of the Chinese population, the majority of whom lived in poverty. Yet within the compound, the family lived a happy life in a residence “like a Florentine villa,” as a family friend would describe.43

These experiences led Henry Luce’s father, Henry [Harry] Winter Luce to develop a “profound affection and admiration for China and the Chinese that would remain throughout his life.”44 Henry Luce would absorb and develop a similarly deep fondness and optimism for China, as James Bradley has described: “Like the Protestant missionaries of his father’s generation, Luce believed that if Christianity would be brought to China, democracy would certainly flow and from there, the development of trade would rapidly ensue.”45 Yet as Luce himself reflected in his younger years, “I know nothing of their [Chinese] social life aside from the formal feasts and holidays.”46

Henry Luce would go on to become one of the most influential figures shaping American perceptions of China in the 1930s and 1940s. After graduating from Yale and Oxford and briefly working as a reporter in Chicago and Baltimore, Luce published the first issue of Time magazine in 1923, followed by the first issue of Fortune in 1930 and the first issue of Life in 1936. The phenomenal success of his magazines—with a total 3.8 million subscribers by 1941—gave Luce a powerful platform to pursue his life’s mission: “the Christianization of China,” as a biographer on Luce has described.47

Like Pearl Buck, Henry Luce helped create “China” for many Americans. Yet, as a Protestant missionary child living in a Westernized enclave in China, his “China”—and the one he created for Americans—was not the real China.

Key Lessons: Assessing the Conditions That Fostered and Propagated Missionaries’ Undue Optimism for China

Missionaries’ undue optimism for China provided a deeply flawed foundation for U.S. policy towards China during the 1930s and 1940s. Analysts seeking to understand why U.S. China policy may have previously erred, and how it could again in the future, should consider the following pitfalls that led missionaries to develop overly idealistic views of China:

Assuming Westernized Chinese Interlocutors Foreshadow a Westernizing China

Missionaries exhibited a recurring tendency to believe that the rise of Westernized Chinese leaders—including Hong Xiuquan, Sun Yat-sen, the “Christian General” Feng Yü-hsiang, and Chiang Kai-shek—were a sign that China itself was Westernizing. In the contemporary era, analysts of China have similarly viewed the appointment of more Westernized Chinese leaders as indications of a more positive trajectory for China.48 Yet the appointment of interlocutors appearing more Westernized or aligned with Western interests has rarely led to China’s Westernization, suggesting analysts should be wary of interpreting the presence of specific Westernized leaders in China as indicative of China’s trajectory. Undue focus on these individuals can give rise to a related error: overweighting the significance of positive statements provided by these Westernized leaders, despite such statements rarely being indicators of policy.

Failing to Distinguish Between China’s More Globally-Oriented South and China’s More Insular North and Interior

The United States’ early missionaries to China were concentrated in the enclaves and treaty ports along China’s southeastern coastline, with their activities restricted to Macau and Canton until 1842, and then expanded to five additional coastal cities until 1860. Protestant missionaries gradually spread inland after the 1860 treaties which concluded the Second Opium War opened access to all of China, but they remained disproportionally concentrated along China’s southeastern coast. Greater exposure to these more Westernized parts of China gave missionaries an inaccurate understanding of China, as missionaries assumed these enclaves to be representative of China more broadly. A similar phenomenon characterizes the contemporary era. Americans know southern China best: the Chinese diaspora is overwhelmingly southern Chinese, global Chinese companies are often headquartered in southern China and dominated by southern Chinese leaders, and American businessmen often have greatest exposure to southern China.49 Yet China’s more insular north has long been the center of political power in China: Chinese dynasties have consistently established their capital city along the peripheries of the Yellow River valley and the Yangtze Delta, whether Nanjing, Xi’an, Luoyang, or Beijing.50 When seeking to forecast China’s potential political trajectory, analysts would likely be better-served by understanding China’s north.

The Power of Favorable Family Experiences in China

Favorable family experiences proved instrumental in shaping how key influencers on U.S. China policy during the 1930s and 1940s—including Henry Luce and Pearl Buck—viewed China. The cases of Luce and Buck should not be considered isolated cases: family experiences with China have proven to be a powerful force shaping how many view China. Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), for example, appears to have also inherited positive views of China from his family. FDR’s grandfather, Warren Delano Jr., was among the early American merchants engaged in China’s opium trade, where he earned a sizable fortune. His daughter Sara, FDR’s mother, grew up in China and inherited romantic views of the nation. She would pass these views down to her children. When FDR decided to continue Secretary of State Henry Stimson’s 1932 policy of non-recognition of Japanese authority in Manchuria, his public support for a Republican position surprised his advisors. To FDR, however, the decision was the only real option, as he admonished his advisers: “I have always had the deepest sympathy for the Chinese. How could you expect me not to go along with Stimson on Japan?”51 Positive family experiences in China could prove similarly influential in the future. Favorable experiences following the opening up of China, for example, may color not only how those analysts view China, but also how their descendants do.52

The Absence of Interpersonal Exchanges Facilitates the Spread of Misconceptions and Provides Actors with Access to China Outsized Influence

With few other ways of understanding China, the United States’ early missionaries had a disproportionate impact on how Americans viewed the Middle Kingdom. Early missionaries’ misconceptions of China were able to take hold in the American imagination because few Americans, including American elites, had any other knowledge of China. Should on-the-ground access to China further close in the contemporary era, actors with continued presence in China could come to have outsized influence on Americans’ understandings of China. The potentially distortive effects of restricting inter-personal exchanges between the United States and China should not be underestimated.

American optimism for China has greatly eroded in recent years, and Protestant missionaries have declined as a force shaping the United States’ China policy. Yet China idealism has proven to be a powerful and enduring force in American foreign policy. Analysts seeking to understand how this idealism has previously led the United States’ China policy to err, and ensure it does not do so again, would be wise to remember the missionaries’ story and the pitfalls that befell them.

_________________

Image: Changsha Church located in Kaifu District of Changsha, Hunan, China on 21 September 2014, from Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Changsha_Church_Christianity_222.JPG, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Elijah Coleman Bridgman and John Robert Morrison, “Letter to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Recent Intelligence from the Missions,” 20 January 1835.

[2] Kapree Harrell-Washington, “From Revered Revolutionary to Much Maligned Marauders: The Evolution of British and American Images in China of the Taiping Rebels,” Miami University, 2008, 16, https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=miami1226167990&disposition=inline.

[3] G. Wright Doyle, “Christianity in China 1900-1950: The History that Shaped the Present,” Global China Center, 22 April 2008, https://www.globalchinacenter.org/analysis/2008/04/22/christianity-in-china-1900-1950-the-history-that-shaped-the-present.

[4] James Bradley, China Mirage, (New York, NY: Back Bay Books, 2015), 39.

[5] Hilary Spurling, “‘Pearl Buck in China,’” New York Times, 8 June 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/09/books/excerpt-pearl-buck-in-china.html.

[6] Harrell-Washington, “The Evolution of British and American Images in China of the Taiping Rebels,” 17.

[7] Owen Lattimore, High Tartary (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1930), 49-50.

[8] Spurling, “‘Pearl Buck in China.’”

[9] Bradley, The China Mirage, 43.

[10] Harrell-Washington, “The Evolution of British and American Images in China of the Taiping Rebels,” 14.

[11] Lattimore, High Tartary, 49-50.

[12] T. Christopher Jespersen, American Images of China, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), 9.

[13] Eric Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in North-West China, (London, UK: Cambridge at the University Press, 1921), 200.

[14] Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in North-West China, 200.

[15] Lattimore, High Tartary, 49-50.

[16] Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in North-West China, 206.

[17] Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in North-West China, 200.

[18] Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in North-West China, 205.

[19] Harrell-Washington, “The Evolution of British and American Images in China of the Taiping Rebels,” 23.

[20] John Douglas Powell, Chiang Kai-shek and Christianity, Texas Tech University, August 1980, 55, https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/bitstream/handle/2346/20280/31295002439635.pdf?sequence=1.

[21] Powell, Chiang Kai-shek and Christianity, 53.

[22] Colin Mackerras, Western Images of China, (London, UK: Oxford University Press, 1989), 24.

[23] Mackerras, Western Images of China, 26.

[24] Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in North-West China, 201.

[25] Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in North-West China, 200.

[26] Edward Stanford, “Map of China: Prepared for the China Inland Mission,” London: Stanford’s Geographical Establishment, 1898, loc.gov/resource/g7820.ct005548/?r=-0.109,0.208,1.355,0.67,0.

[27] Harrell-Washington, “From Revered Revolutionary to Much Maligned Marauders,” 17.

[28] Lattimore, High Tartary, 49.

[29] Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, Christianizing the Heathen: First-Hand Information Concerning Overseas Missions, (London, UK: Watts & Co., Johnson’s Court, 1922), 25.

[30] Harold Isaacs, Scratches on our Minds, (New York, NY: The John Day Company, 1958), 155.

[31] Isaacs, Scratches on our Minds, 155.

[32] Bradley, The China Mirage, 131.

[33] Isaacs, Scratches on our Minds, 155.

[34] Pearl Buck, My Several Worlds: A Personal Record, (New York, NY: Open Road Integrated Media, 1953), https://www.amazon.com/My-Several-Worlds-Pearl-Buck/dp/0899669875.

[35] Spurling, “‘Pearl Buck in China.’”

[36] Spurling, “‘Pearl Buck in China.’”

[37] Buck, My Several Worlds.

[38] Spurling, “‘Pearl Buck in China.’”

[39] Buck, My Several Worlds.

[40] Buck, My Several Worlds.

[41] B.A. Garside, One Increasing Purpose, the Life of Henry Winters Luce, (New York, NY: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1948), 83-84.

[42] Garside, One Increasing Purpose, 132-133.

[43] Garside, One Increasing Purpose, 133-134.

[44] Garside, One Increasing Purpose, 91.

[45] Bradley, The China Mirage, 114.

[46] As quoted in Robert E. Herztein, Henry R. Luce and the America Crusade in Asia, (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 11.

[47] W.A. Swanberg, Luce and His Empire, (New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972), as cited in Bradley, The China Mirage, 113.

[48] Keith B. Richburg, “Li Keqiang: China’s next premier, carries reformers’ hopes,” The Washington Post, 10 November 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/li-keqiang-chinas-next-premier-carries-reformers-hopes/2012/11/09/126800fc-29a3-11e2-aaa5-ac786110c486_story.html.

[49] Qian Song and Zai Liang, “New Emigration from China: Patterns, Causes and Impacts,” National Library of Medicine 26 (2019): 5-31, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8351535.

[50] “Beijing and the Provinces: Geographic Disparities Among CCP Elites,” Baron, September 2022, https://www.baronpa.com/library/beijing-and-the-provinces-geographic-disparities-among-ccp-elites.

[51] Bradley, The China Mirage, 137.

[52] Ryan Cohen, “I have a crush on China,” Twitter, 25 June 2022, https://twitter.com/ryancohen/status/1540485828266164228?s=20; “Tribute,” Teddy Publishing, https://teddy.com/pages/tribute.