In 1964, there seemed to be only two countries with serious space ambitions—the United States and the Soviet Union. After all, the world’s two most wealthy and powerful nations made it their business to point rockets at one another, and the Space Race had flung machine and man alike into orbit. If any other countries could hope to catch up, they would surely be the superpowers’ allies—middle powers like France and the United Kingdom. In reality, however, the Western and Soviet blocs were not alone in their celestial pursuits. By 1964, in Latin America, the governments of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico had already established space programs of their own.1 At the same time in Africa, countries like Kenya were already exploring the theoretical use of earth observation satellites.2 And in Zambia, science teacher (and political revolutionary) Edward Makuka Nkoloso famously claimed that he would launch the first mission to the moon by the end of the year.3

Although the Zambian moon mission never took off, one nascent national space program did see a triumph that year, a feat whose legacy would eventually launch an explosion of new opportunities for developing nations. The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) first successful rocket launch in 1964 was only the beginning for a country that now aims to be the world’s leading space power by 2045.4 Today, the PRC, under the direction of Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), boasts a multibillion-dollar space economy, including nearly 100 commercial space companies.5 Having smashed milestones themselves, these companies offer products and services that are groundbreaking for aspirational countries in Latin America and Africa year after year.6 For developing nations, cooperation with international partners like the PRC to expedite their integration into the global space economy seems only logical. This cooperation, however, is fraught with peril.

The United States and its allies are locked in strategic competition with the PRC across all domains. While widespread attention to Latin America and Africa is a fairly recent phenomenon in American security thinking, the developing world has long been key to the CCP’s global objectives. Simultaneously, the PRC seeks to surpass the United States in space technology. Beijing’s space activities are “designed to advance its global standing and strengthen its attempts to erode U.S. influence across military, technological, economic, and diplomatic spheres,” according to the Department of State’s 2023 Strategic Framework for Space Diplomacy.7 That most space technology is dual-use—able to serve both civil and military purposes—lends credence to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) adage that “whoever controls space controls the earth.”8 Taken together, the Chinese proliferation of space technology throughout the Global South poses a significant security challenge to the United States.

Commercially available “emerging technologies”—rapidly developing technologies with far-reaching but unrealized gains—are powerful instruments for drawing developing nations into their provider’s sphere of influence. Demand for space technology in developing countries has created openings for Chinese products, a portfolio that now includes earth observation data, rocket launch technology, satellite components, and manufacturing techniques. In the Information Age, space is a lucrative business, with a worldwide space economy approaching $500 billion USD as of 2022.9 American commercial space companies have historically outpaced their Chinese competitors in both innovation and revenue, but that gap is shrinking. Moreover, Chinese innovation policies enable the PRC to profit politically as well as financially. Chinese enterprises, many of which are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), execute commercial activities in lockstep with CCP and PLA goals under the doctrine of military-civil fusion. The Chinese gains are thus twofold: with each business transaction, revenue and process knowledge flow upwards to the CCP while influence flows downwards.

As the Sino-American competition heats up, with each side jostling the other for control of space, the United States must not cede any more of the commercial market in the Global South to the People’s Republic of China. The United States still leads the PRC in commercial space technology thanks to its Cold War-era first-mover advantage, but it continues to primarily target the European and Indo-Pacific markets. A historical indifference towards the Global South, coupled with the lack of an export approach that tightly coordinates commercial activities and national strategic objectives, has enabled the PRC to obtain footholds in these emerging markets. Such gains, kickstarted by Beijing’s aggressive economic tactics, unauthorized technology transfers, and American regulatory policy missteps, are accelerating as the Chinese global market share expands. To minimize the spread of Chinese space infrastructure throughout the world, the United States must leverage its booming private sector to compete with the PRC in the Global South while it can still take advantage of its superior space expertise.

Spaced Out

The modern PRC is built on technological ambition. Xi Jinping’s globally focused “China Dream” depends on sustained economic growth, powered by “indigenous innovation” to promote technological self-reliance.10 Space is at the forefront of Beijing’s ambitions. In his 2022 speech to the 20th Party Congress, Xi mentions science and technology, including space, 45 times, a nearly threefold increase from the previous Congress.11 The “Space Dream,” a whole-of-nation strategy to surpass the United States as the dominant space power, flows from the China Dream and is critical to “realizing the Chinese people’s mighty dream of national rejuvenation.”12 The PLA adage about the control of space speaks to the political benefits that are sure to follow.

The China Dream and the Space Dream lie atop the PRC’s decades-long courtship of the “Third World,” an appeal that began as early as the 1950s with the South-South technology-sharing cooperation among non-aligned states.13 For their part, countries in the Global South, having watched the American-Soviet Space Race from the sidelines, are eager to reap space’s benefits in today’s information-driven world. Space literacy is critical to the socioeconomic and political goals of many developing countries, which seek to harness space to address issues ranging from environmental monitoring to disaster management to connectivity. Space innovation can be a catalyst for other technologies that support national modernization objectives, while simultaneously serving as a source of national pride. Speaking for Africa, South Africa’s ambassador to the United Nations summarized in 2021 that the “demand for space products and services is among the world’s highest as the continent’s economy becomes increasingly dependent on space.”14 The new Sino-South space partnership, then, seems to be a match made in the heavens.

The PRC has indeed been effective in building its partnerships in the Global South. Largely framing its cooperative partnerships as “politically disinterested,” the PRC purports to form relationships with countries across the ideological spectrum.15 The apparent open-handed nature of Chinese cooperation makes it a compelling alternative to the more selective American engagement. Beijing’s modern engines for expanding economic and political influence worldwide, including the Belt and Road Initiative, have resulted in trade deals with most of Africa and a large swath of Latin America.16 The new Global Development Initiative seems poised to build on these relationships. Subsequently, surveys conducted across Latin America and Africa routinely reveal favorable views of China and increasing indifference towards the West.17 Princeton University political scientist Aaron Friedberg notes that programs like the Belt and Road Initiative are aimed at nations “hungry for infrastructure and investment and sympathetic to Beijing’s claims that the existing international system is dominated by wealthy, powerful, and arrogant Western nations seeking to impose their values on the rest of the world.”18

That said, for many countries the partnership with the spacefaring PRC is more about convenience than ideology, sympathetic regimes like Venezuela and Zimbabwe aside. Such countries are uninterested in being caught up in a “zero-sum game of Great Power competitive influence,” and the CCP’s global vision is scarcely a motivating factor for cooperation any more than the American vision.19 More generally, “it is often the scale and unrestricted nature of … Chinese largesse” that makes the PRC “an attractive partner.”20 The PRC commands the world’s second-largest government space budget, a rapidly maturing commercial space sector, and a half-century of launch experience.21 Its products and services range from critical infrastructure connected to BeiDou (the Chinese position, navigation, and timing constellation) to satellite phone networks built by SOEs such as China Satcom.22 They also include space launch infrastructure, satellite assembly procedures, and operations facilities.

Most importantly, Chinese companies have the resources, process knowledge, and economies of scale to springboard developing countries into the global space economy. Several countries, such as Ethiopia and Sudan, built and launched their first satellites with help from the PRC.23 Others, like Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nigeria, are working with Chinese companies to launch and operate their own satellite communications networks.24 The success of Chinese influence is evident in Nigeria, a country whose space program began with its 1960s cooperation with National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), but which recently cut a $550 million deal with the PRC for joint ownership of its communications satellites.25 Nigeria is also working with the China National Space Administration to launch researchers to the Tiangong space station and send its students to the PRC for exchange programs.26 The governments of the Global South are, no doubt, beneficiaries of the PRC’s apparent philanthropy. But make no mistake, the PRC’s deliberate approach to technology proliferation has a greater aim: to undermine American global space dominance.

Direct Ascent

For over 50 years, the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in space power competition. By the end of the 1980s, rockets and satellites made by commercial companies—not only governments—were helping to define the boundaries of the competition, including the diplomatic, economic, and military uses of space.27 Yet after decades of threats, a hot war between the great powers never materialized. Instead, they took their fights below the Brandt line: Vietnam, Afghanistan, and finally Iraq, where space power was put to the test.

This first space-arms race culminated in Operation Desert Storm in the twilight of the USSR. Dubbed “the first space war,” the 1991 conflict proved that space was a domain in which wars could be fought and won.28 The victory was due in large part to the United States-led coalition’s asymmetric advantage in space: satellite communications, high resolution imagery, and Global Positioning System (GPS)-enabled precision strikes. The conflict also showed that space technology produced by commercial companies could augment military objectives. Production of GPS receivers and satellite communications terminals surged to meet demand while coalition forces shuffled space infrastructure into the Middle East during the Desert Shield buildup. Meanwhile, military planners were procuring services from providers like Intelsat and France’s SPOT to boost national communications and imagery satellite constellations.29

Although it was fought far from the Indo-Pacific, the First Gulf War was pivotal to the evolution of Chinese space doctrine. The United States was suddenly supremely confident in its space warfare capabilities, and the prospect of the global hegemon’s theater missile defense systems deployed in Asia haunted the CCP.30 Quietly, the PRC began to accelerate its development of countermeasures. According to a 2006 report by the RAND Corporation:

[O]ne PLA source states that during the Gulf War, 90 percent of strategic communications was handled by satellites, including commercial satellites. From the Chinese perspective, successfully attacking U.S. space-based communication systems could have a powerful impact on the ability of the United States to communicate with forces in a given theater of operations.31

The fruit of these observations was the PLA’s successful test of a direct-ascent anti-satellite missile. The 2007 exercise destroyed a defunct Chinese meteorological satellite in low-earth orbit, arguably proving that the United States no longer had unrivaled access to space in any theater it chose.

While the United States has yet to engage the PRC in all-out space battle, commercial technology’s crucial role in modern warfare is nonetheless on full display in Russia’s war in Ukraine. Private American companies are providing the backbone for space-based communication and earth observation for Ukrainian forces in what is being dubbed “the first commercial space war.”32 The year-long Russian troop buildup prior to the full-scale invasion gave American companies like Maxar, Capella Space, and SpaceX plenty of time to integrate their services with American and allied regional commands.33 The lesson for Beijing from the conflict rings as true today as it did in the first space war: the key to the effective use of space in conflict is readiness.

Bits and Orbits

Over the past several decades, the PRC’s access to the Global South has enabled the CCP to expand its interests beyond the purely economic. In some cases, cooperation has extended to arms sales (particularly in Africa), sanctions evasions assistance (through trade with embargoed countries like Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua), and the proliferation of dual-use technologies. Even among democratic countries, Chinese security assistance, including equipment and training, can be seen as “an alluring alternative to U.S. assistance, which is often viewed as slow and restrictive.”34 Such assistance creates opportunities for the CCP to gain new footing around the world, both diplomatically and militarily.

Broadening space power globally requires infrastructure, both physical and digital. But while space-related activities are increasingly easy to track thanks to modern sensors, discerning their ultimate purpose is inherently difficult. Because most space technology is dual-use, commercial application can easily veil military utility. Remote sensing satellites can be used for environmental monitoring and spying. Positioning constellations can guide taxi drivers and munitions. Space ports can launch astronauts and nuclear warheads. As the PRC’s space technology becomes more widely available in the Global South, ostensibly serving peaceful purposes, Chinese infrastructure that could quickly be wielded against the United States expands in critical theaters.

Space infrastructure encompasses more than just spacecraft. Ground stations—operating facilities that track orbiting objects and enable satellite command and control—can be installed even in countries with fledgling space programs. For example, in 2018 Tunisia became the first country outside China to receive a BeiDou ground station, anticipating that the project would boost “technological advance[ment] and economic development in the region.”35 Beyond these apparent economic boosts, ground stations planted around the world provide operators with near-constant access to their satellites. Somewhat ominously, the PRC operates ground stations in at least six countries in the United States’ backyard—Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, and Venezuela.36 Even more ominously, according to a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the PRC’s largest non-domestic space facility, Espacio Lejano, is staffed by personnel from the PLA’s Strategic Support Force, though the Argentinian station was officially built for space exploration.37

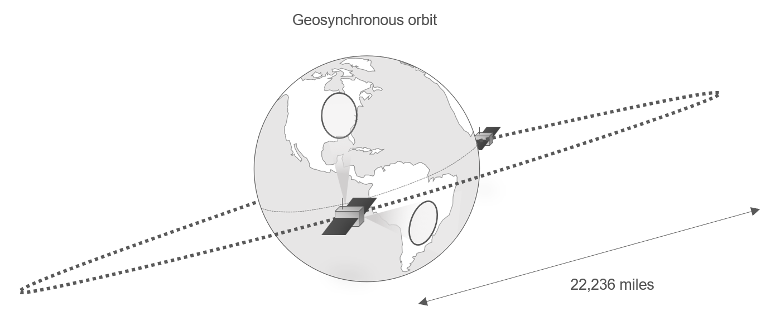

Cooperation with equatorial (or near-equatorial) countries could lead to greater control over geosynchronous satellites. Geosynchronous satellites fly high over the equator, orbiting at the same velocity as the earth’s rotation. This allows them to “hover” over a fixed spot on the earth’s surface, their altitude granting them a wide field of view. Such orbits are clearly useful for communications, but they can also be used for sensing applications such as missile warnings. Countries in the Global South have long recognized their geostrategic advantage: in 1976, several Latin American and African nations signed the Ecuador-led Bogota Declaration in Colombia, asserting their “national sovereign rights” over their airspace extending to the geosynchronous orbit.38 While the PRC was not directly involved (and the Declaration was largely ignored internationally), such cooperation among diverse nations was wrought from the South-South cooperation, and “laid the diplomatic groundwork for the expansion of Latin America-China relations after the turn of the millennium.”39

Figure 1. In geosynchronous orbit, satellites fly high above the equator. They appear to hover over a fixed location and have a wide field of view.40

The Global South’s geostrategic advantages are not limited to global space visibility. In the maritime domain, cooperation with countries like Djibouti (where the PLA Navy currently operates a base) can lead to access to ports and maintenance facilities in a key region.41 Similarly, African and Latin American countries near the equator boast favorable geography for rocket launch sites. Spaceports at mid-latitudes can leverage the Earth’s higher rotational speed at the equator to assist in hurling satellites into space, dramatically flattening launch costs. Chinese-constructed spaceports in countries near the equator would serve as peacetime hubs for international space access. In a conflict, however, should the PLA gain (or retain) access to these sites, it would also have the ability to quickly launch new space assets (“rapid deployment”) to patch or augment depleted or damaged constellations (“reconstitution”).42

In parallel, the “small-sat” and “megaconstellation” revolutions, driven by lower satellite manufacturing and launch costs, create substantial market opportunities in countries hungry for space-based internet and Internet-of-Things. Beijing has already designated space-based internet as a “national infrastructure” project, and created SOE China Satellite Network Group to oversee a 13,000-satellite constellation project, Guowang.43 On the digital side, Chinese engineers are ensuring the constellation will have the network capacity to support worldwide coverage, including in communications-denied environments. As a strategic matter, though, the dual-use capability is apparent: just consider how Starlink, the American broadband internet constellation built and manufactured by SpaceX, has empowered Ukrainian warfighters in the Russo-Ukrainian conflict.44

Tarred and Feathered

Although Chinese space-based internet is still in the early stages, the PRC is already offering functional alternatives to certain space technologies pioneered by Americans. Countries like Kenya that launched their first satellites on American rockets are conducting experiments on the Tiangong space station.45 Competition in newer commercial niches like radio frequency sensing is appearing from entities like China HEAD Aerospace Group (ostensibly a private company with subsidiaries in France).46 The so-called “Space Silk Road” is synchronizing critical infrastructure throughout Africa and Latin America ranging from power grids to financial systems to the BeiDou constellation.47 It seems indisputable that the United States’ space presence in the Global South is eroding, with the tide of Chinese competition becoming more difficult to turn.

Unfortunately, some of the forces that led to this erosion were self-inflicted. Victory in the Cold War established the United States as the predominant space power, and with such a mantle came the emergence of risk-averse regulatory policy. In 1998, satellite technology was reclassified as a “munition” in an effort to tamp down on unauthorized technology transfers to the PRC.48 This meant that satellites and related products were now subject to the United States International Traffic in Arms Regulation (ITAR) authority for military and defense technology. The controversial decision, which was neither technology- nor country-specific, affected trade relations even with the United States’ closest allies and partners. According to testimony from a 2012 House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing, U.S. global market share for space technologies fell from 75 percent before the reclassification to less than 50 percent within a decade.49 Foreign competitors jumped on the opening, ending joint research and development efforts, cutting American parts out of their supply chain, and even infamously advertising their products as “ITAR-free.”50 The 2013 National Defense Authorization Act subsequently softened the “all satellites and related items” clause to boost competitiveness.51

Despite the 2013 reforms, however, American companies have continued to struggle to adapt to the challenges of the long-term global security environment under export control laws like ITAR. While export regulations can be effective for limiting an adversary’s access to highly guarded defense technology, the current regulatory environment remains overly burdensome, frequently ineffective, and even counterproductive— effects that the space industrial base has long decried. For example, radio frequency-sensing products for most end purposes and users continue to be classified as munitions under ITAR, in spite of their non-defense applications.52 These include applications that would be invaluable to many countries in the Global South, such as “environmental stewardship, natural resource protection, and maritime and border security.”53 In many sensing applications, the software that translates raw collected data into useable information is also listed in the U.S. Munitions List, despite employing “internationally well-known processing algorithms that are not specially designed for military or intelligence purposes.”54

On the other hand, Chinese space products are not subject to self-imposed export restrictions, and the list of countries considered CCP export partners is expansive. Additionally, whereas Russia was once the provider of choice for many countries in the Global South, U.S. sanctions in the wake of the Ukraine conflict will likely shrink Russian market share in critical areas such as launch technology, creating even more market opportunities for their Chinese counterparts.55 The PRC is already proliferating space technology once considered American-exclusive, whether the United States objects or not, and at the same time, American actors are struggling to capitalize on the existing demands.

Use the Market Force

Policymakers in the United States are justified in closely guarding top American space expertise from falling into the wrong hands. Of course, Washington should be judicious. Not every technology should be sold to everyone, and companies’ concerns about corruption and intellectual property theft should be taken seriously and addressed. Nonetheless, as long as the PRC continues to offer attractive infrastructure deals to developing countries, the American space sector will find itself increasingly boxed out of the market. Beijing must not be allowed to expand its space offerings uncontested; the United States has no choice but to double down on the competition for the global market. Although non-aligned states may resist being pulled into an ideological struggle between the great powers, they will continue to seek cutting-edge space technology. Both the United States and the PRC stand to benefit from the new revenue streams available.56 Nevertheless, the Americans are in a more favorable position to do so if the United States can more deftly use its thriving commercial sector as an extension of U.S. policy.

To start, the United States must constantly reform its export control policies to fit the global security environment, decreasing the barriers for American companies to sell space-related products on the international market. While regulations have loosened over the years, the regulatory authority continues to stifle commercial innovation across all dual-use technologies. A 2017 study by the UK government estimating a $500 million USD annual cost to its companies due to ITAR suggests that even the United States’ closest allies are exasperated.57 More recently, “ITAR-taint,” where any movement or future use of a product with any ITAR-controlled U.S. input is restricted—even if “predominantly ally-developed”—has been a deep source of contention within the historic Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) trilateral security partnership.58 The 2023 introduction of the TORPEDO Act, which is aimed at reducing regulatory barriers to sharing sensitive technologies within AUKUS, is an innovative step towards solving longstanding issues. The passage and success of the bill would bode well for both the space industry and the prospects of increased cooperation with countries in the Global South.

The deregulation process can be simplified by recognizing that while American commercially available products may eclipse the national programs of many countries in the Global South, much daylight remains between top commercially available and top U.S. national capabilities. Meeting the Global South’s demand for space connectivity does not have to mean selling the blueprints to first-class American designs. Policymakers should clearly distinguish between the different tiers of sophistication and realistic potential for weaponization before considering which technologies—physical or digital—to restrict. Since space exports generally fall under the Departments of State and Commerce, the two should work with the Department of Defense to determine and restrict only the products whose levels of sophistication clearly “provide a critical military or intelligence advantage” to another country where one did not previously exist.59

In addition, authorized dual-use technologies must have proven civil applications and all efforts must be made to ensure their proper use. For example, earth observation data could be restricted to applications like agricultural and environmental monitoring. While the totalitarian CCP proliferates sensing technology that helps illiberal regimes surveil its own citizens, the United States must differentiate itself.60 International customers must never own exclusive rights to assets, data, and networks owned by earth observation companies. American and allied commercial companies must also be required to deploy a “killswitch” at the request of the U.S. government to shut off the flow of services to any non-American or non-allied customer. In the First Gulf War, imagery from the French SPOT satellite was “cut off” from the commercial market at the United States’ request to prevent it from falling into Iraqi hands.61 A similar mandatory mechanism could protect U.S. interests should a crisis or conflict arise involving a country from the Global South.

A coordinated effort to proliferate the right kinds of space technology in tandem with export control laws must come from the top. Space technology should be treated as a priority export, and the United States should work with international partners to gain further access to countries in the Global South. The Office of Space Commerce, an agency with deep subject matter expertise on space, should be elevated to report directly to the Secretary of Commerce, and should be responsible for directing a national roadmap for the export of space technology and infrastructure.62 The office should seek to define the relationship between commercial space products and national security priorities, “establishing a light-touch, presumed-approval process with well-defined timelines.”63

The global security implications of proliferating space technology are clear: containing the spread of Chinese space infrastructure is about deterrence as much as economics. Many countries seek Chinese assistance for its own sake rather than ideological commitment, and they should not be faulted for pursuing a strategy of non-alignment. Consequently, the United States should not appear to seek to use space power to draw any country into a zero-sum-competition with the PRC. Success primarily entails stifling the expanding global network of ground stations, satellites, and space-enabled critical infrastructure controlled by Xi Jinping’s anti-West Chinese Communist Party.

Nevertheless, certain American space enterprises will naturally balance against their blanketly coercive Chinese counterparts, leading to stronger partnerships between the United States and countries in the Global South. In Africa, where only 22 percent of the continent has access to the internet, unmonitored space-based internet will inherently demonstrate the U.S. commitment to the right to self-determination.64 American earth observation data may help to unveil the environmental and economic threat posed by illegal Chinese fishing, mining, and deforestation, especially in South America.65 Shining a light on the PRC’s subversive tactics—including the weaponization of debt and environmental disregard—may make American assistance more attractive in comparison once again.

While Beijing is closing the gap in many key space technologies, the United States still owns a wealth of knowledge and worldwide infrastructure thanks to decades of innovation. Permanent ground stations for GPS alone operate in over a dozen countries on every continent.66 Of the 33 global spaceports with successful satellite launches, Americans own and operate eight, and have also launched rockets from allied countries like Australia. In 2022, the United States launched 180 rockets, heaving hundreds of objects into space, including missions to lap the moon, observe distant galaxies, and provide broadband internet to Ukrainian warfighters.67 The new Space Race in the Global South is Washington’s to lose.

Ultimately, the United States can win the race by leveraging its resilient space industrial base and market principles to offer more innovative, reliable products to developing countries. American commercial expansion in the Global South will either force the PRC to retreat or invite greater investment, inflating the CCP’s risk of overextension and straining its economic resources and diplomatic energy. The United States holds an asymmetric advantage in space expertise that enables companies to enter new markets with lower capital expenditure than their Chinese rivals. Expanding American space infrastructure worldwide through cooperation with the Global South will mean that a pathway to a space domain governed by international rules-based norms is still well within reach. But getting there requires vision, perseverance, and boldness. Since the dawn of the Space Race, the Global South and the People’s Republic of China never stopped taking space seriously. Neither should the United States.

_________________

Image: Hell’s Barrier rocket launch base in Brazil, from flickr.com. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hell%27s_Barrier_(rocket_launch_base)_Brazil_(50883666923).jpg, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Joseph Guzman, “Space Programs in Latin America: History, Current Operations, and Future Cooperation,” Journal of the Americas 3 (2021): 200.

[2] United Nations, Regional Cartographic Conference for Africa (New York: United Nations, 1963), https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1485032.

[3] Pranay Varada, “The Space Race Expands: Why African Nations are Looking Beyond Earth,” Harvard International Review, 15 April 2022, https://hir.harvard.edu/why-african-nations-are-shooting-for-the-stars/.

[4] “A Timeline of China’s Advancements in Spaceflight,” The New York Times, 12 December 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/12/science/china-space-chronology-timeline.html; Arjun Kharpal, “China once said it couldn’t put a potato in space. Now it’s eyeing Mars,” CNBC, 29 June 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/30/china-space-goals-ccp-100th-anniversary.html.

[5] Blaine Curcio, “Developments in China’s Commercial Space Sector,” The National Bureau of Asian Research, 24 August 2021, https://www.nbr.org/publication/developments-in-chinas-commercial-space-sector/.

[6] Neel Patel, “China’s surging private space industry is out to challenge the US,” Technology Review, 21 January 2021, https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/01/21/1016513/china-private-commercial-space-industry-dominance/.

[7] “A Strategic Framework for Space Diplomacy,” U.S. Department of State, 2023, 13, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Space-Framework-Clean-2-May-2023-Final-Updated-Accessible-5.25.2023.pdf.

[8] Dwayne A. Day, “Staring into the eyes of the Dragon,” The Space Review, 14 November 2011, https://thespacereview.com/article/1970/1.

[9] Stefan Ellerback, “The space economy is booming. What benefits can it bring to Earth?,” World Economic Forum, 19 October 2022, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/10/space-economy-industry-benefits.

[10] Aaron Friedberg, Getting China Wrong (Padstow: Polity Press, 2022), 89.

[11] Andrew Jones, “China’s party conclave signals strong support for Xi’s space agenda,” Space News, 20 November 2022, https://spacenews.com/chinas-party-conclave-signals-strong-support-for-xis-space-agenda/.

[12] Kevin Pollpeter, Eric Anderson, Jordan Wilson, and Fan Yang, China Dream, Space Dream: China’s Progress in Space Technologies and Implications for the United States, (IGCC, 2015), 7, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China%20Dream%20Space%20Dream_Report.pdf.

[13] Julie Michelle Klinger, “A Brief History of Outer Space Cooperation Between Latin America and China,” Journal of Latin American Geography 17, no. 2 (July 2018): 51.

[14] United Nations, Regional Cartographic Conference for Africa.

[15] Thomas F. Lynch III, ed., Strategic Assessment 2020: Into a New Era of Great Power Competition (Washington: National Defense University Press, 2020), 272.

[16] David Sacks, “Countries in China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Who’s In and Who’s Out,” Council on Foreign Relations, 24 March 2021, https://www.cfr.org/blog/countries-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-whos-and-whos-out.

[17] Roberto S. Foa, et al., A World Divided: Russia, China and the West, CAM.90281 (Cambridge, UK: 2022), 20, https://doi.org/10.1786 /CAM.90281.

[18] Friedberg, Getting China Wrong, 89.

[19] Lynch, “Strategic Assessment 2020,” 279.

[20] Lynch, “Strategic Assessment 2020,” 282.

[21] Simon Seminari, “Government Space Budgets Surge Despite Global Pandemic,” Via Satellite, December 2020, https://interactive.satellitetoday.com/government-space-budgets-surge-despite-global-pandemic/.

[22] Jonathan Shieber, “China Nears Completion of Its GPS Competitor, Increasing the Potential for Internet Balkanization,” Tech Crunch, 28 December 2019, https://techcrunch.com/2019/12/28/china-nears-completion-of-its-gps-competitor-increasing-the-potential-for-internet-balkanization/.

[23] Kate Barlett, “Why China, African Nations Are Cooperating in Space,” VOA News, 13 September 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/why-china-african-nations-are-cooperating-in-space/6745595.html.

[24] Vidya S. R. Avuthu, China’s design to capture regional SatCom markets (ORF, 2018), 2, https://www.orfonline.org/research/chinas-design-to-capture-regional-satcom-markets/.

[25] Olajide Aluko, “Nigeria and the Superpowers,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 5, no. 2 (September 1976): 127-141; House Keeper, “Nigeria, other African countries in space science technology cooperation with China,” Blueprint NG, 5 September 2022, https://www.blueprint.ng/nigeria-other-african-countries-in-space-science-technology-cooperation-with-china/.

[26] Keeper, “Nigeria, other African countries in space science technology cooperation with China.”

[27] Lyn Dutton et al., Military Space, (UK: Brassey’s, 1990), 98.

[28] Craig Covault, “Desert Storm Reinforces Military Space Direction,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, 8 April 1991, 42.

[29] “Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, Final Report to Congress,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 1992, 648-649, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA249270.

[30] U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People’s Republic of China, U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People’s Republic of China, 3 January 1999, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., 1999, S. Rep 105-851, 1-206, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRPT-105hrpt851/pdf/GPO-CRPT-105hrpt851.pdf.

[31] James Mulvenon et al., Chinese Responses to U.S. Military Transformation and Implications for the Department of Defense (Santa Montica: Rand Corporation, 2006), 69.

[32] Sandra Erwin, “On National Security | Drawing lessons from the first ‘commercial space war’,” Space News, 20 May 2022, https://spacenews.com/on-national-security-drawing-lessons-from-the-first-commercial-space-war/.

[33] Betsy Woodruff Swan, Paul McLeary, “Satellite images show new Russian military buildup near Ukraine,” Politico, 1 November 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/11/01/satellite-russia-ukraine-military-518337.

[34] Lynch, “Strategic Assessment 2020,” 279.

[35] “Middle East Regional GNSS Cooperation Updates,” GPS World, https://www.gps.gov/governance/advisory/meetings/2018-05/rashad.pdf; Tracy Cozzens, “BeidDou inaugurates first overseas center in Tunisia,” GPS World, 11 April 2018, https://www.gpsworld.com/beidou-inaugurates-first-overseas-center-in-tunisia/.

[36] Matthew P. Funaiole, Dana Kim, Brian Hart, Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Eyes on the Skies,” in Hidden Reach (CSIS, 2022), https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/china-ground-stations-space/.

[37] Funaiole, “Eyes on the Skies.”

[38] Klinger, “A Brief History of Outer Space,” 54.

[39] Klinger, “Outer Space Cooperation,” 54.

[40] Figure 1: Geosynchronous orbit. Figure by the author.

[41] John Fei, “China’s Overseas Military Base in Djibouti: Features, Motivations, and Policy Implications,” The Jamestown Foundation, 22 December 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-overseas-military-base-djibouti-features-motivations-policy-implications/.

[42] Harrison, “Dark Arts in Space,” 16.

[43] Andrew Jones, “The coming Chinese megaconstellation revolution,” Space News, 23 February 2023, https://spacenews.com/the-coming-chinese-megaconstellation-revolution/.

[44] Christopher Miller, Mark Scott, Bryan Bender, “UkraineX: How Elon Musk’s space satellites changed the war on the ground,” Politico, 9 June 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/06/09/elon-musk-spacex-starlink-ukraine-00038039.

[45] Chad de Guzman, “China’s Space Ambitions Are Fueling Competition and Collaboration,” Time, 31 October 2022, https://time.com/6226631/china-space-station-mengtian-launch/.

[46] Erik Kulu, “Satellite Constellations – 2021 Industry Survey and Trends,” 35th Annual Small Satellite Conference, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5092&context=smallsat.

[47] John Dotson, “The Beidou Satellite Network and the ‘Space Silk Road’ in Eurasia,” China Brief 20, no. 12 (July 2020): 2.

[48] Ryan Zelnio, “A short history of export control policy,” The Space Review, 9 January 2006, https://www.thespacereview.com/article/528/1.

[49] Patricia A. Cooper, “Hearing on Export Controls, Arm Sales, and Reform: Balancing U.S. Interests (Part II),” House Foreign Affairs Committee, 7 February 2012, https://sia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/SIA-ITAR-Written-Testimony-for-HFAC-Hearing-2012-02-07.pdf.

[50] “U.S. space industry ‘deep dive’ assessment: impact of U.S. export controls on the space industrial base,” U.S. Department of Commerce, February 2014, 1, https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/technology-evaluation/898-space-export-control-report/file.

[51] Dara Panahy, Bijan Ganji, “ITAR Reform: A Work in Progress,” The Air & Space Lawyer 26, no. 3 (2013): 2.

[52] “Satellite Industry Association Earth Observation Forum Working Group White Paper,” Satellite Industry Association, 17 October 2022, 1, https://sia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/PR22-2022.10.17-SIA-Earth-Observation-Forum-WG_Export-Policy.pdf.

[53] “Satellite Industry Association White Paper,” 1.

[54] “Satellite Industry Association White Paper,” 1.

[55] Jeremy Grunert, “Sanctions and satellites: the space industry after the Russo-Ukrainian War,” War on the Rocks, 10 June 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/06/sanctions-and-satellites-the-space-industry-after-the-russo-ukrainian-war/.

[56] Tom Roeder, “State of Space 2022: Industry Enters ‘Era of Access and Opportunity’,” The Space Report, 2022, https://www.thespacereport.org/uncategorized/state-of-space-2022-industry-enters-era-of-access-and-opportunity/.

[57] William Greenwalt, “Leveraging the national technology industrial base to address great-power competition,” The Atlantic Council, 2019, 14, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Leveraging_the_National_Technology_Industrial_Base_to_Address_Great-Power_Competition.pdf.

[58] William Greenwalt, Tom Corben, “Breaking the barriers: reforming US export controls to realise the potential of AUKUS,” United States Studies Centre, 17 May 2023, https://www.ussc.edu.au/analysis/breaking-the-barriers-reforming-us-export-controls-to-realise-the-potential-of-aukus.

[59] 26 U.S.C. § 120.3.

[60] Bulelani Jili, China’s Surveillance Ecosystem & The Global Spread Of Its Tools, (Atlantic Council, 2022), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/chinese-surveillance-ecosystem-and-the-global-spread-of-its-tools/.

[61] Steven Bruger, “Not Ready for the ‘First Space War,’ What About the Second?,” Naval War College, 17 May 1993, 18.

[62] Olson, “Space Industrial Base,” 94.

[63] Karina Drees, “Why the Office of Space Commerce should supervise novel commercial space activities,” Space News, 14 March 2023, https://spacenews.com/why-the-office-of-space-commerce-should-supervise-novel-commercial-space-activities/.

[64] Emmanuel Abara Benson, “15 Countries with the lowest internet penetration in Africa,” Business Insider Africa, 6 July 2022, https://africa.businessinsider.com/local/markets/15-countries-with-the-lowest-internet-penetration-in-africa/gpm8kc7.

[65] “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” Office of the Director of National Intelligence, February 2022, 18, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2022-Unclassified-Report.pdf.

[66] “Control Segment,” gps.gov, https://www.gps.gov/systems/gps/control/.

[67] Alexandra Witze, “2022 was a record year for space launches,” Nature.com, 11 January 2023, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00048-7.