“¡Pobre México! ¡Tan lejos de Dios y tan cerca de los Estados Unidos!” (Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States!)

Attributed to former Mexican President Porfirio Díaz and widely known in Mexico, the remark partially captures the complicated relationship between the United States and its southern neighbor. This long history, spanning the spectrum between war and peace, has resolved into what today represents one of the world’s largest bilateral economic relationships and almost immeasurable, multi-generational cultural bonds linking millions of people.

Stronger U.S.-Mexico ties could bring both countries significant benefits, yet continued challenges and a complex history create obstacles on both sides of the Rio Grande. Since 2018, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) has pursued a “Fourth Transformation” of the country by concentrating economic and political power in the Mexican State, resulting in a poor economic record during his first three years and declining foreign investment.[1] AMLO also has a concerning penchant for illiberalism that threatens the country’s democratic institutions.[2] More broadly, AMLO has pursued a strategic shift away from the United States that has created significant challenges in bilateral relations.[3]

In Washington, American leaders have often treated Mexico as a country that is a source of problems for the United States to manage and damaged the bilateral relationship with inflammatory rhetoric from the executive branch and Congress. Migration and drug and human trafficking at the U.S.-Mexico Border are security and humanitarian crises that leaders in both countries must take seriously and address in the short and long term. However, U.S. officials cannot lose sight of the importance of a strong relationship with Mexico for successfully addressing the crisis, as well as nearly 5 million American jobs supported by trade across that same border.[4]

The challenges in the U.S.-Mexico relationship are complicated by the competition and, increasingly, confrontation between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). While the PRC has become a focal point for American economic and national security policy discussions, Washington has paid relatively little attention to the PRC’s growing activity in Mexico. Notably, Beijing has strengthened its formal ties with Mexico over the last decade, and Chinese companies have won contracts for several significant infrastructure projects central to AMLO’s agenda. These efforts are part of a broader PRC strategy to develop economic and diplomatic partnerships in Latin America that fortify Chinese global economic power and advance the PRC’s priorities in multilateral institutions.

Just as Mexico has long viewed U.S. intervention with suspicion, the United States has historically feared foreign influence in Mexico. In 1917, Germany’s brazen attempt to coax Mexico to join its war effort famously contributed to the U.S. decision to enter the First World War.[5] During the Cold War, the Soviet Union’s KGB station in Mexico City was a major base for espionage operations against the United States, including the theft of advanced U.S. technology for transfer to the Communist bloc.[6] In this century, the PRC’s increasing attention on Mexico presents a combination of national security, economic, and political concerns for the United States that are new in the post-Cold War era.

The PRC’s growing activity in Mexico represents a significant potential threat to U.S. homeland and economic security. If left unchecked, these efforts threaten to erode U.S. influence in Mexico, harm the long-term competitiveness of U.S. and Western companies in the country, and undermine Mexican democratic and economic progress. Considering Mexico’s proximity to the United States and the scale of the bilateral economic relationship, Beijing’s focus there could degrade U.S. power at a time when Washington is facing global challenges from the PRC, Russia, and other adversaries.

To confront this challenge and strengthen both countries, U.S. policymakers should seize this opportunity to intensify American engagement with Mexico. Washington should utilize the full range of U.S. diplomatic and economic tools to compete vigorously with the PRC in Mexico and strengthen bilateral cooperation while preventing Beijing from having the ability to threaten U.S. influence and security interests. At the same time, it is neither realistic nor practical for the United States to pressure Mexico to decouple from the PRC. Instead, U.S. strategy should focus on areas in which Chinese activity threatens national security or democratic values, undermines Mexico’s long-term economic future, or prevents foreign firms from competing by controlling critical infrastructure or putting intellectual property at risk. If successful, this approach can provide a model for U.S. engagement in other Latin American countries.

The benefits to the United States of a revitalized relationship with Mexico are immense and go beyond mitigating PRC threats to U.S. interests. With continued progress addressing economic and rule of law challenges, Mexico could be a central part of the U.S. economic arsenal and a key destination for ally-shoring U.S. supply chains. Realizing this vision would make both countries more prosperous and bolster U.S. economic power as it enters a potentially prolonged global competition with the PRC.

Strategic Partnerships

The foundation of the modern U.S.-Mexico relationship is the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and its successor, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Effective in 1994, NAFTA signaled that Mexico’s leaders sought a new path in its relationship with the United States and that U.S. leaders would stand with them. Most immediately, the agreement locked in Mexico’s domestic economic reforms by tying them to more favorable treatment of Mexican goods in the U.S. market and committed the Mexican government to continue opening up its market to North American trade as provisions of NAFTA came into effect.[7] In effect, NAFTA’s binding commitments created a glide path for a phase of significant economic liberalization in Mexico. This transformed one of the world’s most protectionist countries into an integral participant in global markets.[8] The economic benefits for the U.S. have been remarkable: Mexico’s total U.S. goods trade increased by more than six times from 1994–2021, and overall U.S. trade with NAFTA partners has more than tripled and grown faster than trade with the rest of the world.[9] In 2021, Mexico was the United States’ second largest trading partner, surpassed only by Canada, with total bilateral goods trade exceeding $661 billion.[10]

A democratic transition accompanied Mexico’s economic changes. In 2000, Vicente Fox defeated the long-ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party in the presidential election, the first opposition victory since the Mexican Revolution.[11] These developments created significant economic opportunities for the United States and improved bilateral relations, but there were also challenges in that same period with significant security and political consequences for both countries, including millions of Mexican nationals crossing into the United States illegally as well as a violent drug war that killed tens of thousands of Mexicans and threatened U.S. border communities.[12]

Mexico-PRC Relations

Mexico and the PRC established diplomatic relations in 1972 on the eve of President Richard Nixon’s arrival in Beijing to launch the U.S. opening to China.[13] Since Mexico began diplomatic relations with the PRC, it has adhered to a “One China” policy while maintaining unofficial ties with Taiwan.[14] Both Mexico and Taiwan have offices in their respective capitals, and Mexican officials continue to meet with senior Taiwanese officials.

Until the turn of the century, trade and investment flow between Mexico and the PRC remained relatively small. The PRC’s integration into the global economy, however, raised concerns that Chinese exports would compete directly with Mexican products in key markets. In 2001, Mexico was the last country to agree to the PRC’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), holding out to secure a bilateral agreement to protect Mexican industries against Chinese goods.[15] Despite these efforts and NAFTA’s preferential trading rules, Mexico lost U.S. market share to the PRC in a significant number of sectors between the PRC’s WTO accession and 2010.[16] Amid this trade competition, Mexico’s relationship with the PRC continued to grow. The PRC became Mexico’s second largest trading partner behind the United States in 2003.[17] That same year, Mexican President Vicente Fox and PRC Premier Wen Jiabao announced the two countries would establish a “strategic partnership” that would include an inter-governmental standing committee to guide bilateral cooperation, people-to-people exchanges, and trade.[18]

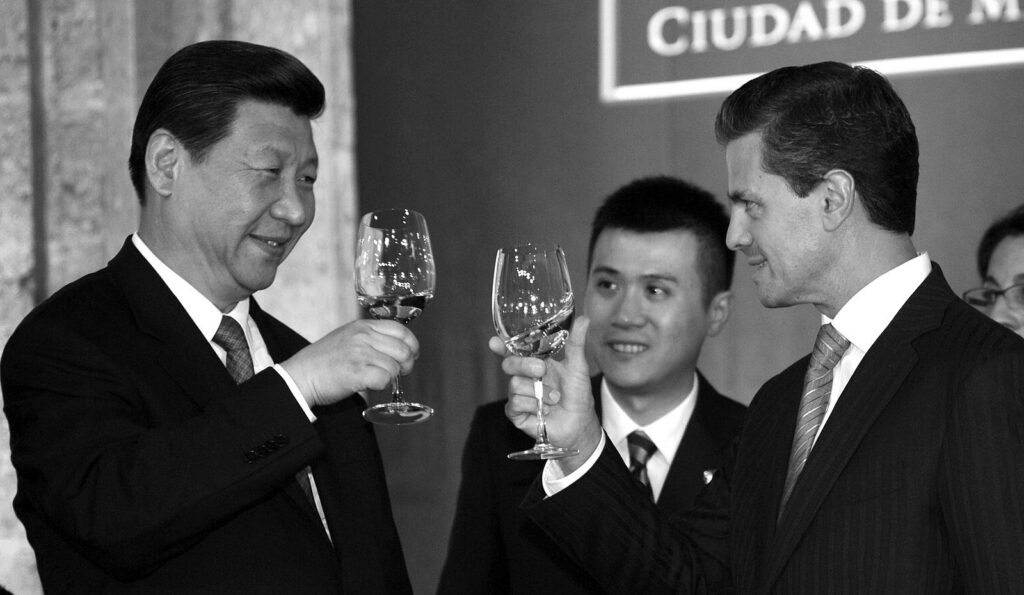

Under PRC President Xi Jinping, Sino-Mexican relations entered a new era. In June 2013, less than three months after becoming president, Xi traveled to Mexico City for a state visit hosted by Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto.[19] The visit was significant because the PRC formally upgraded the Sino-Mexican relationship to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” Mexico is one of seven countries in Latin America, including Argentina and Brazil, the PRC has accorded this status, which is believed to denote countries where Beijing seeks economic, technological, cultural, and political cooperation through both bilateral and multilateral relationships.[20] Xi’s visit reciprocated a trip by Peña Nieto to Beijing two months earlier.[21] This flurry of bilateral diplomatic activity by two relatively new leaders represented an attempt to improve ties after decades of trade competition in the U.S. market. In the years following the Xi visit, the Peña Nieto administration welcomed Chinese investment, establishing a $2.4 billion investment fund with the PRC to support infrastructure, mining, and energy projects.[22]

Beijing’s Aims

Public policy statements and diplomatic engagements provide insights into the PRC’s strategy in Latin America and Mexico. In November 2016, the PRC released its most recent white paper on Latin America and the Caribbean. The paper provides some public insights into Beijing’s regional priorities but does not mention Mexico directly. It acknowledges that PRC engagement in the region is strategically important to the continued growth of the Chinese economy and state and includes relationships across the economic, military, political, and social domains.[23]

For Mexico, Chinese officials outlined several specific priorities during the 2022 commemorations of the 50-year anniversary of PRC-Mexico diplomatic relations. President Xi said in a statement that he “attach[ed] great importance to the development of China-Mexico relations” and sought to “continuously enrich the China-Mexico comprehensive strategic partnership.”[24] PRC Ambassador to Mexico Zhu Qingqiao said that his country would prioritize working with Mexico on “desarrollo de alta calidad” (high-quality development) and offered to pursue common development through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which Mexico has not joined. Zhu also emphasized the importance of diplomatic collaboration, including multilateralism at the United Nations and through the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC).[25] While these public statements should face some skepticism, they provide insight into the priorities that the PRC is articulating to Mexican audiences.

The PRC’s objectives in Latin America have raised increasing alarm in Washington. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC) wrote in its 2021 Annual Report that the PRC’s economic engagement in the region aims to secure commodities and raw materials for the Chinese economy and “[build] markets for its companies and technologies.”[26] Concerningly, however, USCC also concluded that “China’s economic importance and targeted political influence encourage Latin American and Caribbean countries to make domestic and foreign policy decisions that favor China while undermining democracies and free and open markets.”[27] As U.S. Army War College professor Dr. Evan Ellis told the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee in March 2022, “the PRC is attempting to ‘rewire’ the region and the world to its own economic benefit.”[28]

Ultimately, U.S. concerns about the ambitions of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Mexico are rooted in geographic proximity and economic security. Mexico’s 1,954-mile land border with the United States and lack of a formal U.S. security alliance make it an ideal platform for adversaries to conduct espionage and threaten U.S. homeland security in a way that distracts from the projection of American power near their borders. This proximity combined with the country’s $101 billion U.S. foreign investment stock and $661 billion in annual U.S. goods trade make it a natural target for undermining U.S. economic power.[29] Leaders in both Washington and Mexico City must keep these concerns in mind as they address the impact of the PRC on the U.S.-Mexico relationship.

Economic Ambitions

The intensification of Sino-Mexican ties has facilitated a growing flow of exports and investment from the PRC. Under AMLO, Secretary of Foreign Affairs Marcelo Ebrard has openly solicited additional Chinese investment and made it a priority to expand the bilateral strategic partnership.[30] From 2013–2019 total trade between the PRC and Mexico increased by 32 percent, outpacing growth in Mexico’s overall trade and its trade with the United States.[31] Notably, PRC exports to Mexico make up over 90 percent of bilateral trade and are skewed toward medium and high-tech products, while Mexico primarily exports raw materials to the PRC.[32] Despite these trends, Mexico’s U.S. trade continues to far exceed trade with the PRC. On the investment side, outward foreign direct investment transactions involving PRC firms in Mexico exceeded $12.5 billion from 2013–2020, of which $9.3 billion has been announced since 2017.[33]

Infrastructure Projects

Until recently, PRC companies have struggled to complete infrastructure projects in Mexico. In November 2014, China Railway Construction Corporation and several partners won a $3.8 billion contract to build a high-speed train from Mexico City to Querétaro.[34] However, the Secretariat of Communication and Transport revoked the contract and later suspended the project amid a corruption scandal involving President Peña Nieto’s wife, growing political opposition to the project, and questions about the transparency of the bidding process.[35] Predictably, Beijing responded negatively, and Chinese construction firms did not take on another major project in Mexico until 2020.[36]

Two PRC state-owned enterprises—China Communications Construction Corporation (CCCC) and CRRC Group—recently won contracts totaling $2.7 billion for Mexican public transit construction projects. In April 2020, a consortium led by Portuguese construction conglomerate Mota-Engil and CCCC won the contract for the first section of the Tren Maya (Maya Train).[37] Conceived by AMLO as an economic development project to link tourist destinations in the Yucatán Peninsula, the rail project is expected to cost more than $8 billion and has faced pushback because of its cost as well as environmental concerns.[38] In Mexico City, a subsidiary of CRRC Group won a $1.9 billion contract to modernize the city’s Metro Line No. 1.[39]

Both firms, however, have faced U.S. sanctions.[40] CRCC was identified as a “Communist Chinese military company” and sanctioned for its ties to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) during the Trump Administration, though the Biden Administration removed the CRCC sanctions.[41] CCCC is designated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury as a Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Company (CMIC) because of its PLA ties.[42] Civilian construction companies are a key component of the PRC’s Military-Civil Fusion Development Strategy.[43] Overseas projects help develop construction and logistics capabilities that the PLA can leverage for military purposes while providing revenue to support projects closer to home.

CCCC and its subsidiaries are also an instrument for projecting PRC state power abroad. The company is among the firms of choice for BRI projects around the world.[44] CCCC’s role in advancing the PRC’s discredited claims in the South China Sea through island-building projects led the U.S. Department of Commerce to restrict the transfer of U.S. technology to the company.[45] In response to these activities, then-U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs David Stilwell called CCCC and its partners “modern-day equivalents of the East India Company” in 2020.[46]

The participation of a state-owned PRC company in constructing a politically high-profile project accentuates AMLO’s desire to increase economic ties with the PRC. Despite public U.S. concerns about CCCC that predated sanctions, the Mexican government awarded the company a contract for one of AMLO’s signature priorities that is expected to kick off a series of development projects in southern Mexico.[47] This decision went largely unnoticed in Washington, but it is part of a broader problem: since 2019 three U.S. partners in the Indo-Pacific—Australia, the Philippines, and Singapore—inked a combined $5.5 billion in CCCC projects despite similar U.S. concerns.[48]

Digital Economy

Mexico is also front in the CCP’s global push to make its companies leaders in technology infrastructure and services. In 2017, Huawei Technologies won the contract to supply equipment for most of Mexico’s new nationwide wireless cellular and internet network, the Red Compartida (Shared Network). Created to introduce more competition in the country’s telecommunications industry, the new network will improve coverage and serve as the primary vehicle for Mexico’s future 5G rollout. Huawei will supply equipment for the network in southern and central Mexico, while Nokia will cover the northern part of the country. Reportedly, the government divided the contract to address American concerns about Huawei building telecommunications infrastructure near the U.S.-Mexico Border.[49] While preventing Huawei from developing the entire network was a step forward for U.S. diplomacy, the company’s robust presence in Mexico illustrates the challenges facing the United States and its allies in the global technology competition.

Huawei’s growing presence in Mexico comes despite years of U.S. pressure to block the company’s expansion there.[50] Under both the Trump and Biden Administrations, the U.S. government has raised significant concerns about Huawei, its ties to the Chinese government, and its business practices.[51] The company is currently sanctioned as a CMIC for ties to the PLA and barred from accessing U.S. technology, particularly semiconductors.[52] Of particular concern, Huawei is subject to the PRC’s Cybersecurity Law that requires technology companies to provide assistance to state security organs for “preserving national security and investigating crimes.”[53] The law does not place limits on this authority and enshrined the ability of Chinese security agencies to use the country’s technology firms to advance the CCP’s interests overseas.

For all intents and purposes, however, the United States had already lost this round of the Huawei contest in Mexico over the past decade. Since 2011, Huawei has won at least four major contacts with Mexican cellular providers, including the Red Compartida tender, and the company claimed in 2019 that it ran more than half of the 4G network hardware in the country.[54] This existing market presence and relationship with the Mexican government created obstacles for U.S. diplomatic arguments about Huawei’s security and reliability. Huawei’s reach in Mexico is also broader than cellular data networks. The company partnered with the government to build more than 30,000 public WiFi hotspots across the country.[55] Additionally, Huawei’s cloud services arm already operates one data center in Mexico and announced plans to open a second as part of the company’s push to gain market share in Latin America.[56]

A significant role for PRC companies in Mexico’s economic life raises several concerns for the United States and would undermine U.S. influence. As described above, overseas construction projects provide the PRC with capabilities and revenue to support strategic infrastructure initiatives in China. In the technology sector, USCC noted that widespread adoption of Chinese technology in Latin American countries would create security risks for sensitive information. This could make U.S.-Mexico security cooperation more difficult and deter U.S. investment because of concerns about intellectual property theft. More broadly, USCC warned that Chinese companies would have the ability to build an interoperable suite of technology tools and standards that could “dictate the long-term structure of the region’s digital economy and influence which technologies are operable within its infrastructure.”[57] Domination in these areas would give the PRC the ability to exclude U.S. and Western companies from parts of Mexico’s digital economy, undermining their ability to compete and do business in the country.[58]

Energy Investment Roadblocks

Unpredictable government policies, the targeting of foreign firms, and corruption have made Mexico’s investment climate less favorable to U.S. companies in recent years. According to the U.S. Department of State’s 2021 Mexico investment climate statement, investors raised concerns about “sudden regulatory changes and policy reversals,” while businesses operating report that corruption is common and government procurement is largely driven by favoritism towards preferred firms.[59] These challenges go beyond bureaucratic issues and are exemplified by difficulties in Mexico’s energy sector, where PRC investment aides AMLO’s political objectives.

In 2013, reforms by the Peña Nieto administration opened Mexico’s energy sector to investment by private and foreign companies for the first time in nearly 80 years.[60] The goal of the reforms was to make the energy sector more efficient, which would increase oil and gas production, reduce energy prices, and boost Mexico’s economy.[61] AMLO, however, is working to undo these reforms and reassert government control to advance his Fourth Transformation agenda. The current Mexican government has canceled private sector auctions for oil and gas drilling.[62] AMLO’s party also passed a controversial energy law giving power plants operated by the state-owned electric utility (CFE) preference over private competitors.[63] In April 2022, AMLO fell short in the Mexican Congress of the two-thirds threshold required to adopt constitutional changes that would give CFE full control of the electric grid and force private power companies to sell to the government.[64]

Additionally, the government has used its regulatory authorities against foreign firms. In July 2021, the Secretariat of Energy gave Mexico’s state petroleum company (PEMEX) effective control of an exploration block in the Gulf of Mexico that it shared with a group of companies led by Houston-based Talos Energy.[65] Mexico’s energy regulator also seized a fuel-storage terminal from Houston-based Monterra energy, whose investors are weighing a potential challenge under USMCA.[66] These actions threaten to freeze new foreign energy investments and deter U.S. and Western firms from entering the Mexican market in other sectors.

In contrast, the PRC has stepped up its investments in Mexico’s energy sector. After the 2013 reforms, China National Offshore Oil Corporation won several Gulf of Mexico exploration blocks in a 2016 auction.[67] The Peña Nieto administration also established a $5 billion Energy Fund between PEMEX, China National Petroleum Corporation, and several Chinese banks that provide financing for energy projects (SINOMEX).[68] Beyond the oil and gas industry, the PRC’s State Power Investment Corporation acquired Zuma Energía, Mexico’s largest private renewable energy provider, in 2020.[69]

A notable beneficiary of the PRC’s support for PEMEX is the controversial Dos Bocas refinery project. Initiated to help realize AMLO’s vision to make Mexico self-sufficient in fuel consumption, the massive project has suffered from delays and cost overruns that have raised its potential cost to as much as $18 billion.[70] Through the SINOMEX Energy Fund, Chinese banks provided $600 million in financing to PEMEX before the project began. The Mexican government denies that the loan was earmarked explicitly for Dos Bocas.[71] Whether earmarked or not, financing from Chinese banks freed up resources for PEMEX to undertake the project instead of bringing in private investment to increase Mexico’s refining capacity or strengthening PEMEX’s relationship with U.S. refiners.

The availability of financing and investment in the energy sector from the PRC provides AMLO with a source of capital to backstop his efforts to roll back Mexico’s energy reforms. As Dr. Evan Ellis pointed out in his 2021 testimony before USCC, PRC economic support has enabled populist leaders across Latin America to strengthen the role of the state in the economy and undermine the private sector.[72] While there is no evidence that AMLO deliberately sought out PRC assistance to advance these policies, the economic incentives are clear. If Chinese investments are protected, Beijing will remain a willing economic partner despite policies that deter investment by non-Chinese firms.

Predictably, the U.S. government has raised concerns about AMLO’s energy initiatives. U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm told officials during a January 2021 trip to Mexico City that the proposed policies would negatively affect U.S. investment in Mexico.[73] As the U.S. pressures the Mexican government to uphold its economic commitments, the availability of Chinese capital provides an alluring alternative path for AMLO. Embracing energy reforms could have increased Mexico’s contribution to global oil markets and created spare production capacity to tap into in a crisis. Given the recent oil supply shock after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the stakes of AMLO’s energy policies and PRC influence in Mexico for U.S. economic security could not be clearer.

Mexico’s Missing Strategy

The United States’ China challenge is further complicated by the Mexican government’s lack of a strategic approach for its relationship with the PRC. If Mexico is going to continue engaging with the PRC while preserving and strengthening its ties with the United States, its government must take the challenge of balancing these relationships seriously. Unfortunately, Mexico does not have a strategy for its relationship with the PRC. The Secretariat of Foreign Affairs does not have an official strategy for engagement with the PRC, and Mexico’s Congress has not enacted significant policy-making legislation on the relationship with China.

Enrique Dussel Peters, who runs the Center for Mexico-China Studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, argues that Mexican leaders have largely avoided defining what Mexico wants from China in the short-, medium-, and long-term.[74] Former Mexican Ambassador to the United States Martha Bárcena Coqui echoes these concerns and advocates for a strategy that encourages more constructive U.S. engagement in Mexico and the region.[75] Mexican public opinion does not provide clear answers either—2021 polling by Western Kentucky University found that a majority of the Mexican public held favorable views of the PRC and the United States and that positive feelings toward both countries were correlated.[76]

Given the importance of the U.S.-Mexico relationship, the view from Washington will be part of Mexico City’s calculus on China, though its influence will depend on how American leaders handle the bilateral relationship in the coming years. Ambassador Bárcena deftly captures this dynamic:

“[W]hile the economic and foreign policy decisions that Mexico will adopt regarding China will also affect the U.S., a constant presence and partner, they will be based on its own national interest—on what is good for Mexico and the Mexicans. Still, a confrontation between the U.S. and China will benefit neither Mexico nor its neighbors.” [77]

In the economic arena, the United States and the PRC are already at odds, making a deliberate Mexican policy for relations with both countries essential for Mexico’s prosperity and close ties with its northern neighbor. For the United States, there is an opportunity to protect U.S. interests and shape Mexico’s approach towards China.

In the absence of a defined strategy, AMLO’s Mexico has cooperated with the PRC in recent years on the COVID-19 pandemic and provided diplomatic support for the PRC’s regional priorities. Mexico sought PRC assistance during the pandemic, purchasing more than 32 million doses of Chinese COVID-19 vaccines, compared to more than 44 million purchased and donated doses from the United States.[78] In December 2021, the CELAC-China Forum, which Mexico and the PRC co-chaired, adopted a Joint Action Plan (2022-2024) that endorsed Chinese priorities in the region for cooperation on issues such as the economy and health.[79] Mexico’s high-level engagement with the CELAC-China Forum demonstrates AMLO’s desire to maintain close ties with the PRC and provides backing to Beijing’s efforts to elevate multilateral groupings in the region that exclude the United States.[80]

Priorities for the United States

The U.S. approach for competing with the PRC in Mexico and protecting U.S. economic and security interests should be part of a broader strategy for the bilateral relationship. For far too long, the United States has struggled to develop and consistently implement a strategic approach to the economic, political, and security relationship with Mexico. This approach must address the ongoing border crisis while not losing sight of other important areas of the relationships. These issues are connected and affect the ability of U.S. policy to address the China challenge, with continued security challenges in Mexico threatening to hold back growth and investment and make cooperation with the PRC more appealing. It is also incumbent on U.S. leaders to communicate clearly to the Mexican government the importance of protecting American economic and security interests in Mexico from external threats.

Improving the U.S.-Mexico relationship will not be easy. The list of problems continues to lengthen: declining cooperation between U.S. and Mexican law enforcement agencies amid a migration crisis and rising cartel violence, increasing trade tensions as Mexico fails to live up to its USMCA commitments, attacks against the country’s electoral authority and Supreme Court by AMLO, and a foreign policy increasingly at odds with U.S. priorities in the Western Hemisphere.[81] Confronting these challenges, however, is essential for the United States and Mexico to realize the full potential of their relationship and reduce PRC-Mexico ties that threaten U.S. interests.

Several tools are available to the United States to foster a stronger democracy and more open economy in Mexico while competing with the PRC. Given the importance of Mexico to the United States, the funding and human capital required to utilize these tools effectively are relatively cheap compared to the potential costs of eroding U.S. influence in the country. The U.S. Department of State and other cabinet agencies should step up diplomatic engagement with Mexico on economic, security, and rule of law issues, including through existing forums such as the High-Level Economic Dialogue.[82] These diplomatic initiatives should include discussions on opportunities to increase U.S.-Mexico cooperation and candid conversations about challenges in the bilateral relationship, including where Mexico’s ties with the PRC raise security and economic concerns. Bolstering Mexico’s democracy will also require increasing U.S. assistance to Mexican civil society groups and working with U.S.-based non-governmental organizations to help build local capacity.[83] To lock in progress made through these bilateral diplomatic efforts and maximize the success of USMCA, the United States, Canada, and Mexico should establish a norm of holding annual North American Leaders’ Summits.

Security cooperation is another important tool. Since 2007, the Mérida Initiative has formalized security cooperation between the two countries and provided more than $3.3 billion in assistance to combat transnational criminal organizations and improve the rule of law in Mexico.[84] In recent years, the Initiative has faced criticism in both capitals despite initial successes.[85] Both governments must make the ongoing effort to replace the Mérida Initiative with a new security framework a serious attempt to improve security cooperation and see it through.[86]

On the economic front, U.S. engagement should seek to improve the investment climate and facilitate the provisioning of cost-effective and sustainable alternatives to PRC economic initiatives. U.S. and Western firms will be more likely to explore opportunities in Mexico and bid on government contracts if the economic climate is improving, not worsening. Under USMCA, there is a strong foundation for bilateral economic ties with trade terms and investment protections unavailable to the PRC that should be central to these efforts.

An often-overlooked economic tool that can play an important role in Mexico is development finance. Expanding U.S. development finance activities can help increase Mexico’s economic potential and provide alternative sources of financing to the PRC. At the end of 2021, the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) had a portfolio of 32 projects in Mexico totaling $1.2 billion. Less than half of committed funds in DFC’s Mexico portfolio, however, were initiated since 2017.[87] In the context of billions of dollars in PRC financing and investment funds focused on Mexico, DFC should be doing more. DFC achievements in other parts of the world provide models for what success could look like in Mexico. Notably, DFC provided financing to a consortium led by U.K.-based Vodafone that won the contract to build Ethiopia’s 5G network, beating a competing bid that had financing from the PRC and would have used Huawei and ZTE hardware.[88]

Congress should also authorize U.S. support for an Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) capital increase. A multilateral development bank with a long history of supporting successful economic development in Latin America, IDB already has an active project portfolio totaling nearly $1.5 billion in Mexico.[89] Expanding IDB’s lending capacity will strengthen the region’s proven partner for infrastructure and development projects and make Chinese capital less attractive.

Futuro Juntos

In 2022, the United States and Mexico are celebrating 200 years of diplomatic relations.[90] At this important juncture, the Biden Administration, Congress, and their Mexican counterparts must make important decisions that will have lasting effects on the bilateral relationship.

After more than a year in office, the Biden Administration has not defined significant parts of its strategy for addressing the China challenge.[91] This uncertainty, particularly on economic and trade policy, denies allies and partners certainty on U.S. policy and makes it more difficult to compete against the PRC. In the case of Mexico, U.S. leaders should clearly identify sectors that implicate critical security or commercial interests and focus their diplomacy, assistance, financing, and commercial initiatives on those areas, making sure to communicate to Mexican counterparts U.S. redlines for PRC investment and provide viable alternatives backed by U.S. or allied economic support.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s leaders must decide whether to continue deepening the country’s reliance on Chinese companies and investment for major government projects, whether to make the hard choices necessary to improve the investment climate and change course on misguided, state-centric economic policies, and how to improve Mexico’s security situation. Additionally, the PRC’s September 2021 request to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement among 11 Pacific nations that includes Mexico and Canada, will require Mexico to have more clarity on its diplomatic and economic relations with Beijing and balance that relationship with its obligations under USMCA.[92] The answers to these questions will largely depend on AMLO in the near-term, but with the next Mexican presidential election looming in 2024, new leaders could step forward and influence policy. A strategic shift by Mexico away from the United States is not in the interest of either country, and difficult work will be required to repair these issues.[93]

The PRC represents the most important threat to U.S. interests and national power. While confronting this challenge, Washington cannot ignore the PRC’s ambitions in its own backyard—or the needs of, and challenges facing, its allies and partners. The success of a prosperous and democratic Mexico is far more important to the national security and economic strength of the United States than American leaders and U.S. policies have indicated over the past decade. It is time that Washington recognizes this reality and deepens its engagement with Mexico City.

Connor Pfeiffer is Executive Director of the Forum for American Leadership. Previously, Connor served as national security advisor to U.S. Representative Will Hurd (R-TX), for whom he was an associate staffer for the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and Committee on Appropriations. He was a 2021-2022 Security and Strategy Seminar China fellow, and is a 2022-2023 Russia fellow.

_________________

Image: Cena de Estado que en honor del Excmo. Sr. Xi Jinping, Presidente de la República Popular China, y de su esposa, Sra. Peng Liyuan, 4 June 2013, from flickr.com. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cena_de_Estado_que_en_honor_del_Excmo._Sr._Xi_Jinping,_Presidente_de_la_Rep%C3%BAblica_Popular_China,_y_de_su_esposa,_Sra._Peng_Liyuan_%288960384656%29.jpg, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Jesus Cañas and Chloe Smith, “Investment in Mexico Falls Despite Rise in Remittances,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 29 June 2021, https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2021/0629.aspx; Earl Anthony Wayne, “Mexico’s AMLO presses for victory and country’s ‘fourth transformation’,” The Hill, 2 June 2021, https://thehill.com/opinion/international/555943-mexicos-amlo-presses-for-victory-and-countrys-fourth-transformation.

[2] Shannon O’Neil, “Mexico’s Democracy Is Crumbling Under AMLO,” Bloomberg, 9 March 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-03-09/mexico-s-democracy-is-crumbling-under-amlo.

[3] “Mexico’s Strategic Shift Away from the United States Threatens National Security,” Forum for American Leadership, 12 June 2022, https://forumforamericanleadership.org/mexico-shift.

[4] Christopher Wilson, Growing Together: How Trade with Mexico Impacts Employment in the United States, The Mexico Institute (Washington, DC: Wilson Center, 2016), 1, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/growing_together_how_trade_with_mexico_impacts_employment_in_the_united_states.pdf.

[5] “The Zimmermann Telegram,” U.S. National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/zimmermann.

[6] Joel Brinkley, “Mexico City Depicted as a Soviet Spies’ Haven,” New York Times, 23 June 1985, https://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/23/world/mexico-city-depicted-as-a-soviet-spies-haven.html.

[7] M. Angeles Villarreal and Ian Fergusson, “The North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA),” Congressional Research Service, 24 May 2017, 9, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42965.

[8] Andrew Chatzky, James McBride, and Mohammed Aly Sergie, “NAFTA and the USMCA: Weighing the Impact of North American Trade,” Council on Foreign Relations, 1 July 2020, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/naftas-economic-impact#chapter-title-0-2.

[9] Chatzky, McBride, and Sergie, “NAFTA and the USMCA: Weighing the Impact of North American Trade”; “Trade in Goods with Mexico,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c2010.html.

[10] “Top Trading Partners – December 2021,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/top/top2112yr.html.

[11] Roderic Ai Camp, “Democratizing Mexican Politics, 1982–2012,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, 2 April 2015, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.12.

[12] Shannon O’Neil, “The Real War in Mexico,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2009, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/mexico/2009-07-01/real-war-mexico.

[13] Enrique Dussel Peters, “China’s Overseas Foreign Direct Investment in Mexico (2000–2018),” in China’s Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean, ed. Enrique Dussel Peters (México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Centro de Estudios China-México, 2019), 310, https://dusselpeters.com/CECHIMEX/20190804_CECHIMEX_Libro_Chinas_Foreign_Direct_Enrique_Dussel_Peters.pdf.

[14] “Manual De Organización de la Oficina de Enlace en México en Taiwán,” Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores de Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 22 July 2014, 5, https://sre.gob.mx/images/stories/docnormateca/comeri/2014/mooftaiwan.pdf.

[15] Joseph Kahn, “China Clears Last Hurdle On Path to Trade Group,” New York Times, 15 September 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/15/world/china-clears-last-hurdle-on-path-to-trade-group.html; Elizabeth Olson, “Beijing Clears Major WTO Obstacles,” New York Times, 4 July 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/04/business/worldbusiness/IHT-beijing-clears-major-wto-obstacles.html.

[16] Enrique Dussel Peters and Kevin Gallagher, “NAFTA’s Uninvited Guest: China and the Disintegration of North American Trade,” CEPAL Review 110 (August 2013): 105, https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/37000.

[17] “Mexico Trade (2019),” World Integrated Trade Solution, accessed 11 January 2022, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountrySnapshot/en/MEX.

[18] “China, Mexico establish strategic partnership,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 13 December 2003, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ce/ceee/eng/dtxw/t111998.htm.

[19] “President Xi Jinping Holds Talks with Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto Two Heads of State Announce Upgrading China-Mexico Relationship to Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America, 5 June 2013, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/ceus//eng/zgyw/t1048352.htm.

[20] Margaret Myers and Ricardo Barrios, “How China Ranks Its Partners in LAC,” The Dialogue, 3 February 2021, https://www.thedialogue.org/blogs/2021/02/how-china-ranks-its-partners-in-lac/.

[21] Elisabeth Malkin, “Chinese President Makes Bridge-Building Trip to Mexico,” New York Times, 4 June 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/05/world/americas/xi-makes-bridge-building-trip-to-mexico.html.

[22] “China, Mexico eye $7.4 billion in investment funds,” Reuters, 13 November 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-mexico/china-mexico-eye-7-4-billion-in-investment-funds-idUSKCN0IX0IF20141113.

[23] R. Evan Ellis, “China’s Second Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean: Indications of Chinese Intentions, and Recommendations for the U.S. Response,” EconVue, 13 December 2016, https://econvue.com/pulse/china-latin-america-and-caribbean-us-sphere-influence; “Full text of China’s Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean,” People’s Daily, 24 November 2016, http://en.people.cn/n3/2016/1124/c90000-9146474.html.

[24] “Xi Jinping Exchanges Messages of Congratulations with Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador on the 50th Anniversary of the Establishment of China-Mexico Diplomatic Ties,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 14 February 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/kjgzbdfyyq/202202/t20220214_10642128.html.

[25] Qingqiao Zhu, “La hora se ilumina,” in 50 Años de Relaciones Diplomáticas Entre México y China. Pasado, Presente y Futuro, ed. Enrique Dussel Peters (México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Centro de Estudios China-México, 2022), 49–54, http://dusselpeters.com/CECHIMEX/Cechimex_2022_50_aniversario_relaciones_diplomaticas_Mexico_China.pdf.

[26] “China’s Influence in Latin America and the Caribbean,” in 2021 Annual Report to Congress of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2021), 80, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/Chapter_1_Section_2–Chinas_Influence_in_Latin_America_and_the_Caribbean.pdf.

[27] “China’s Influence in Latin America and the Caribbean,” 100.

[28] R. Evan Ellis, “China’s Role in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Testimony before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere, Transnational Crime, Civilian Security, Democracy, Human Rights, and Global Women’s Issues, 31 March 2022, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/congressional_testimony/ts220331_Ellis_Testimony.pdf?Yjf9iiy14ntLWuOfUn8LcxsYE0ldI32y.

[29] “2021 Investment Climate Statements: Mexico,” U.S. Department of State, https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-investment-climate-statements/mexico/; “Top Trading Partners – December 2021.”

[30] Emile Sweigart and Gabriel Cohen, “Mexico’s Evolving Relationship with China,” Americas Quarterly, 19 October 2021, https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/mexicos-evolving-relationship-with-china/.

[31] “Mexico Trade (2019).”

[32] Enrique Dussel Peters, “The New Triangular Relationship between Mexico, the United States, and China: Challenges for NAFTA,” in The Renegotiation of NAFTA. And China?, ed. Enrique Dussel Peters (México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Centro de Estudios China-México, 2018), 92–94, https://www.redalc-china.org/v21/images/Renegotiation_NAFTA_China_ALTA.pdf.

[33] “OFDI Monitor in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Latin American and Caribbean Academic Network on China (Red ALC-China), 2021, https://www.redalc-china.org/monitor/.

[34] “Mexico to compensate China’s CRCC for canceling rail project,” Reuters, 21 May 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/mexico-china-train/mexico-to-compensate-chinas-crcc-for-canceling-rail-project-idUSL1N0YD03620150522.

[35] Fermín Koop, “Chinese rail advances slowly in Latin America,” Diálogo Chino, 1 October 2019, https://dialogochino.net/en/infrastructure/30573-chinese-rail-advances-slowly-in-latin-america/.

[36] Enrique Dussel Peters, “Chinese Infrastructure Projects in Mexico,” in Building Development for a New Era: China’s Infrastructure Projects in Latin America and the Caribbean, ed. Enrique Dussel Peters, Ariel C. Armony, and Shoujun Cui (México: Red ALC-China and University of Pittsburgh/CLAS, 2018), 64–66, https://www.redalc-china.org/v21/images/Red-ALC-China-y-U-PittsburghBuilding-Development2018.pdf.

[37] Pablo Hernández, “Chinese-backed Mayan train chugs ahead despite environmental fears,” Diálogo Chino, 24 July 2020, https://dialogochino.net/en/infrastructure/36609-mayan-train-advances-with-chinese-support/.

[38] “AMLO’s Mayan Train: Pros and cons,” El Universal, 29 August 2018, https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/english/amlos-mayan-train-the-pros-and-cons.

[39] Paloma Duran, “CRRC to Modernize Mexico City’s Metro Line 1,” Mexico Business News, 1 December 2020, https://mexicobusiness.news/infrastructure/news/crrc-modernize-mexico-citys-metro-line-1.

[40] “Executive Order 13959 of November 12, 2020, Addressing the Threat From Securities Investments That Finance Communist Chinese Military Companies,” Federal Register 85, no. 222 (11 November 2020): 73185-73189, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/11/17/2020-25459/addressing-the-threat-from-securities-investments-that-finance-communist-chinese-military-companies.

[41] “DOD Releases List of Additional Companies, In Accordance with Section 1237 of FY99 NDAA,” U.S. Department of Defense, 14 January 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2472464/dod-releases-list-of-additional-companies-in-accordance-with-section-1237-of-fy/.

[42] “Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List,” U.S. Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control, 16 December 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/consolidated-sanctions-list/ns-cmic-list.

[43] Office of the Secretary of Defense, “2021 Report on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, 3 November 2021, 24–29, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2831819/dod-releases-2021-report-on-military-and-security-developments-involving-the-pe/.

[44] Kate O’Keefe and Chun Han Wong, “U.S. Sanctions Chinese Firms and Executives Active in Contested South China Sea,” Wall Street Journal, 26 August 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-imposes-visa-export-restrictions-on-chinese-firms-and-executives-active-in-contested-south-china-sea-11598446551.

[45] U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security, “Addition of Entities to the Entity List, Revision of Entry on the Entity List, and Removal of Entities From the Entity List,” Federal Register 85, no. 246 (22 December 2020): 83416-83432, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/12/22/2020-28031/addition-of-entities-to-the-entity-list-revision-of-entry-on-the-entity-list-and-removal-of-entities.

[46] David R. Stilwell, “The South China Sea, Southeast Asia’s Patrimony, and Everybody’s Own Backyard,” U.S. Department of State, 14 July 2020, https://2017-2021.state.gov/the-south-china-sea-southeast-asias-patrimony-and-everybodys-own-backyard/index.html.

[47] Roman Ortiz, “Mexico, China & the US: A Changing Dynamic,” Americas Quarterly, 25 January 2021, https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/mexico-china-the-us-a-changing-dynamic/.

[48] “China Global Investment Tracker.”

[49] Julia Love, “U.S. campaign against Huawei hits a snag south of the border,” Reuters, 9 May 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mexico-huawei-tech-insight/u-s-campaign-against-huawei-hits-a-snag-south-of-the-border-idUSKCN1SF15Z.

[50] Garrett Graff, “Inside the Feds’ Battle Against Huawei,” Wired, 16 January 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/us-feds-battle-against-huawei/.

[51] Justin Sherman, “The U.S. Is Continuing Its Campaign Against Huawei,” Lawfare, 20 July 2021, https://www.lawfareblog.com/us-continuing-its-campaign-against-huawei.

[52] Ana Swanson, “U.S. Delivers Another Blow to Huawei With New Tech Restrictions,” New York Times, 15 May 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/business/economy/commerce-department-huawei.html.

[53] Jack Wagner, “China’s Cybersecurity Law: What You Need to Know,” The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2017/06/chinas-cybersecurity-law-what-you-need-to-know/; “2016 Cybersecurity Law,” China Law Translate, 7 November 2016, https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/2016-cybersecurity-law/.

[54] Drew FitzGerald, “The U.S. Wants to Ban Huawei. But in Some Places, AT&T Relies On It.,” Wall Street Journal, 16 April 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-u-s-wants-to-ban-huawei-at-t-mexico-relies-on-it-11555407001.

[55] “Huawei and Mexico Build Largest Public Wi-Fi in Latin America,” Huawei, https://e.huawei.com/in/case-studies/global/2018/201809181700.

[56] Cinthya Alaniz Salazar, “Huawei Opens Second Cloud Region,” Mexico Business News, 26 October 2021, https://mexicobusiness.news/tech/news/huawei-opens-second-cloud-region; Dan Swinhoe, “Huawei planning second Mexico data center, more across Latin America,” Data Center Dynamics News, 26 August 2021, https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/huawei-planning-second-mexico-data-center-more-across-latin-america/.

[57] “China’s Influence in Latin America and the Caribbean,” 93.

[58] Greg Levesque, “Reshaping the Battlefield: The Security Implications of China’s Digital Rise,” in China’s Digital Ambitions: A Global Strategy to Supplant the Liberal Order, ed. Emily de La Bruyère, Doug Strub, and Jonathon Marek (Washington: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2022), 90, https://www.nbr.org/publication/reshaping-the-battlefield-the-security-implications-of-chinas-digital-rise/.

[59] “2021 Investment Climate Statements: Mexico.”

[60] Emilio Godoy, “Explainer: Why is Mexico reforming its energy sector – again?,” Diálogo Chino, 24 February 2022, https://dialogochino.net/en/climate-energy/explained-why-is-amlo-mexico-energy-reform-electricity.

[61] Daniel Yergin, “Behind Mexico’s Oil Revolution,” Wall Street Journal, 18 December 2013, https://www.wsj.com/articles/daniel-yergin-behind-mexico8217s-oil-revolution-1387411480.

[62] Godoy, “Explainer: Why is Mexico reforming its energy sector – again?.”

[63] Marla Verza, “Mexico high court OKs preference for state power plants,” Washington Post, 7 April 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/mexico-high-court-oks-preference-for-state-power-plants/2022/04/07/af3bc0ee-b6d9-11ec-8358-20aa16355fb4_story.html.

[64] Drazen Jorgic and Dave Graham, “Mexican president’s contentious electricity overhaul defeated in Congress,” Reuters, 18 April 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/mexican-lawmakers-vote-presidents-contentious-electricity-overhaul-2022-04-17/.

[65] Anthony Harrup, “Mexico Hands Control of Large Oilfield to Pemex in Dispute With U.S.’s Talos,” Wall Street Journal, 5 July 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/mexico-hands-control-of-large-oilfield-to-pemex-in-dispute-with-u-s-s-talos-11625512620?page=1&mod=article_inline.

[66] Mary Anastasia O’Grady, “KKR vs. Mexico’s López Obrador,” Wall Street Journal, 21 February 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/kkr-mexico-lopez-obrador-amlo-investment-monterra-energy-oil-terminal-export-monopoly-nafta-usmca-arbitration-tribunal-11645463328?mod=opinion_featst_pos1; “Mexico Moves to Seize American Assets,” Wall Street Journal, 17 October 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/mexico-american-assets-obrador-amlo-energy-11634496785.

[67] Robbie Whelan and Anthony Harrup, “Australia’s BHP Billiton Wins Bidding for Stake in Mexico’s Trion Oil Field,” Wall Street Journal, 5 December 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/australias-bhp-billiton-wins-bidding-for-stake-in-mexicos-trion-oil-field-1480957642.

[68] Matthew Hughes, “China’s Incursion into Energy Sectors of Latin American Hydrocarbon Giants,” SAIS China Studies Review, 31 July 2021, https://saiscsr.org/2021/07/31/csr-blog-chinas-incursion-into-energy-sectors-of-latin-american-hydrocarbon-giants/; “Mexico, China & the US: A Changing Dynamic.”

[69] Cas Biekmann, “Chinese Energy Player Acquires Mexico’s Zuma Energía,” Mexican Business News, 23 November 2020, https://mexicobusiness.news/energy/news/chinese-energy-player-acquires-mexicos-zuma-energia.

[70] Amy Stillman, Lucia Kassai, and Max De Haldevang, “Mexico’s Crown-Jewel Oil Refinery Is $3.6 Billion Over Budget,” Bloomberg, 21 January 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-21/mexico-s-crown-jewel-oil-refinery-is-3-6-billion-over-budget; “AMLO’s Dos Bocas refinery cost doubles to $18 billion USD,” Yucatan Times, 23 June 2022, https://www.theyucatantimes.com/2022/06/amlos-dos-bocas-refinery-cost-doubles-to-18-billion-usd/; “Mexico, China & the US: A Changing Dynamic.”

[71] “Bancos chinos financiarán 600 millones de dólares de la refinería de Dos Bocas,” El Economista, 13 January 2020, https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/empresas/Bancos-chinos-financiaran-600-millones-de-dolares-de-la-refineria-de-Dos-Bocas-20200113-0027.html.

[72] R. Evan Ellis, “China’s Diplomatic and Political Approach in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Testimony before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 20 May 2021, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-05/Evan_Ellis_Testimony.pdf.

[73] “Statement by U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm on Travel to Mexico City, Mexico,” U.S. Department of Energy, 21 January 2022, https://www.energy.gov/articles/statement-us-secretary-energy-jennifer-m-granholm-travel-mexico-city-mexico.

[74] Enrique Dussel Peters, “México: ¿T-MEC y/o CPTPP con China?,” Voces México, 27 September 2021, https://vocesmexico.com/opinion/mexico-t-mec-y-o-cptpp-con-china/.

[75] Martha Bárcena Coqui, “Why Mexico’s Relationship with China Is So Complicated,” Americas Quarterly, 28 September 2021, https://americasquarterly.org/article/why-mexicos-relationship-with-china-is-so-complicated/.

[76] Timothy Rich, Ian Milden, Madelynn Einhorn, and Olivia Blackmon, “Gauging the Mexican view of US-China rivalry,” East Asia Forum, 1 October 2021, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/10/01/gauging-the-mexican-view-of-us-china-rivalry/.

[77] Bárcena Coqui, “Why Mexico’s Relationship with China Is So Complicated.”

[78] Samantha Kane Jiménez and Arianne Gandy, “Mexico’s Vaccine Supply and Distribution Efforts,” Wilson Center Mexico Institute, 4 October 2021, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/infographic-mexicos-vaccine-supply-and-distribution-efforts.

[79] R. Evan Ellis and Leland Lazarus, “China’s New Year Ambitions for Latin America and the Caribbean,” The Diplomat, 12 January 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/01/chinas-new-year-ambitions-for-latin-america-and-the-caribbean/; “Mexico chairs the 3rd Ministerial Meeting of the Celac-China Forum,” Secretariat of Foreign Affairs of the United Mexican States, 3 December 2021, https://www.gob.mx/sre/prensa/mexico-chairs-the-3rd-ministerial-meeting-of-the-celac-china-forum?idiom=en.

[80] Ellis and Lazarus, “China’s New Year Ambitions for Latin America and the Caribbean.”

[81] “Mexico’s Strategic Shift Away from the United States Threatens National Security.”

[82] Shannon O’Neil, “Mexico’s Democracy is Crumbling Under AMLO,” Bloomberg, 9 March 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-03-09/mexico-s-democracy-is-crumbling-under-amlo; “FACT SHEET: U.S. – Mexico High-Level Economic Dialogue,” The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/09/fact-sheet-u-s-mexico-high-level-economic-dialogue/.

[83] O’Neil, “Mexico’s Democracy is Crumbling Under AMLO.”

[84] Clare Ribando Seelke, “Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, FY2008-FY2022,” Congressional Research Service, 1 November 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10578; “Mexico: Background and U.S. Relations,” Congressional Research Service, 7 January 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42917.

[85] Roberta Jacobson, Arturo Sarukhan, Laura Carlsen, Raúl Benítez Manaut, and Rubén Olmos Rodríguez, “Has the Mérida Initiative Failed the U.S. and Mexico?,” The Dialogue, 17 August 2021, https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/has-the-merida-initiative-failed-the-u-s-and-mexico/.

[86] Earl Anthony Wayne, “Mexico: Highest U.S. Priority in the Western Hemisphere,” Council of American Ambassadors, 3 November 2021, https://www.americanambassadorslive.org/post/mexico-highest-u-s-priority-in-the-western-hemisphere.

[87] “All Active Projects as of 12/31/21,” U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, accessed 31 January 2022, https://www.dfc.gov/our-impact/all-active-projects.

[88] Stu Woo and Alexandra Wexler, “U.S.-China Tech Fight Opens New Front in Ethiopia,” Wall Street Journal, 22 May 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-china-tech-fight-opens-new-front-in-ethiopia-11621695273.

[89] “Mexico,” Inter-American Development Bank, accessed 30 January 2022, https://www.iadb.org/en/countries/mexico/overview.

[90] “A Guide to the United States’ History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Mexico,” U.S. Department of State, https://history.state.gov/countries/mexico.

[91] Bob Davis, “Biden Promised to Confront China. First He Has to Confront America’s Bizarre Trade Politics.,” Politico Magazine, 31 January 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/01/31/biden-china-trade-politics-00003379.

[92] Enrique Dussel Peters, “México: ¿T-MEC y/o CPTPP con China?,” Voces México, 27 September 2021, https://vocesmexico.com/opinion/mexico-t-mec-y-o-cptpp-con-china/.

[93] “Mexico’s Strategic Shift Away from the United States Threatens National Security.”