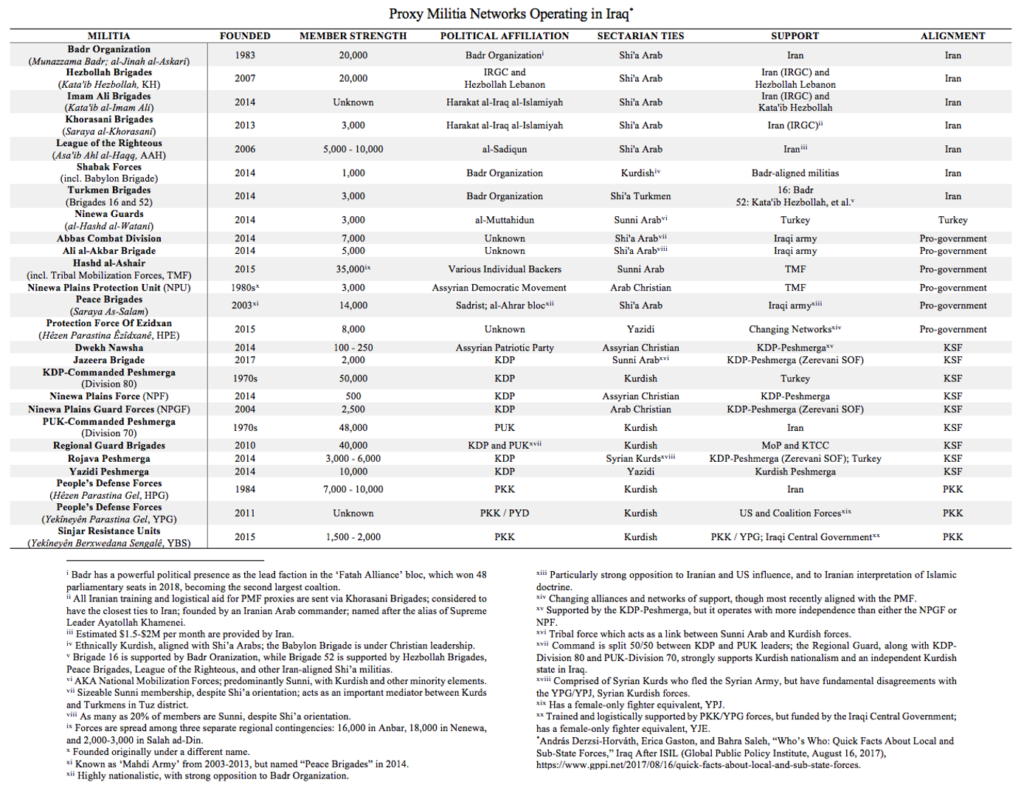

Iran’s foreign policy conjures imagery of a spider and its entangling web, each thread representing a proxy to be called upon to ensnare an adversary. Indeed, Iran has built an impressive network of non-state surrogates that operate on its behalf or, at least, further its strategic goals. Most of Iran’s state and sub-state partners have Shi’a affiliations, which has tangible consequences. In Syria, the Sunni-majority demographic left Iran with few indigenous actors to fight on its behalf and forced it instead to call upon its sectarian-aligned proxies in Lebanon and Iraq. When contrasted with the deep network of Shi’a proxies that make up Al-Hash al-Shaabi in Iraq, also known as the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), the value of sectarian loyalty is hard to deny.[1] However, the theological rhetoric employed by the Islamic Republic is sometimes misused by policy analysts as a determinant of Iranian sponsorship. Despite the usefulness of sectarian analysis, political considerations lay the foundation on which layers of factional cleavages are built. While its alliances often follow religious lines, Iran’s proxy bonds are rooted in political underpinnings that inform foreign policy strategies for both parties. In this way, Iran’s formative revolutionary ideology both exploits and transcends sectarian divides to further its goals. Along with pragmatic reasons for its intricate network of surrogates, Tehran’s ideological commitment to enfranchise oppressed Islamic groups is fundamental to its sponsorship of rebel militias. This ethos informs the Islamic Republic’s Shi’a Crescent ideology (unifying the geopolitical mass that encompasses Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon to the west; Yemen to the south, nominally including Gulf States like Bahrain), but also motivates it to fund non-Shi’a militias that align with its anti-West worldview.

The use of indigenous militias to fight and win wars is neither a new phenomenon, nor a strategy unique to Iran. By utilizing local proxies, states gain a combative edge and distance themselves from the political blowback of becoming entangled in foreign wars. Still, despite the ubiquity of proxy sponsorship, Iran implements this strategy particularly effectively. Its propensity for relying on proxies is due to its revolutionary ideology as well as political and financial constraints.

Former Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomenei envisaged an Islamic Republic that would champion the oppressed throughout the Muslim world. His revolutionary ideology necessitated a bottom-up approach by enfranchising insurgencies across the region in an attempt to upset the status quo and fight Western influence. Tehran recognizes the limitations of its mobility and has developed a policy of surrogate warfare, tailored to its capacities within the global power structure. Largely unchecked after Saddam Hussein’s removal in 2003, Tehran’s self-appointed role as the regional opposition to Saudi Arabia has become even more pronounced. However, from the Islamic Republic’s establishment, economic sanctions and political ostracization have smothered its commercial opportunities and access to evolving weapons technologies, relegating it to a geopolitically disadvantaged position. Due to this global pariah status, Iran must utilize less conventional means to opportunistically fill the hegemonic cracks. Its inability to develop a powerful conventional armed forces has caused Iran to rely on asymmetrical tactics implemented through indigenous proxies abroad.

Tehran is foremost a patient strategist, with its eyes on the long game, rather than short-term victories, and this farsighted acumen is integral to Iran’s proxy relationships. However, few states are sufficiently dominant to influence sub-state groups without playing political chess—not least of all Iran, with its constrained capital and lacking hegemonic position. As a result, for these proxy relationships to weather the course of enduring conflict and evolving geostrategic landscapes, Iran must navigate a system of give-and-take with its surrogates.

Foundations of Revolutionary Ideology and Strategies of the Shi’a Crescent

Central to Iran’s military apparatus is its elite Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), formed as a militant body to serve the new Islamic leadership, who were distrusting of the Western-style Iranian Army.[2] IRGC leadership is so enmeshed within the system, through parliamentary posts and other positions of authority, that its influence is beyond extrication. Domestically, the corps protects the Supreme Leader and his structure of power by suppressing dissidents, from communists to monarchists. At home and abroad, the IRGC is mandated by the constitution to protect the revolutionary ideals, including its ideological marriage to the concept of Velayat-e Faqih. This foundational dogma espouses the concept of political rule by a supreme religious jurisprudence—“the merging of political and religious authority under the most learned cleric.”[3] The Islamic Republic operates under this system of rule today and, in its early years was deeply committed to the export of Islamic revolution, making numerous attempts to implement its form of governance across the region. Its closest proxies, like Hezbollah in Lebanon and in Iraq, have (at one time or another) embraced the religious principle.

From 1979 through the mid-1980s, Iran actively pursued a policy which sought to implant the velayat across the region, but this policy changed due to internal and external factors. Within Iran, ideological zealotry tempered, particularly after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989. Outside its borders, attempts to implement the religious system of governance failed—as was the case in Lebanon—and proxies embraced more nationalistic goals, though they often remained loyal to the Islamic Republic’s greater strategic interests. ‘Exporting the Islamic revolution’ shifted from a religious goal to a political imperative, though the dogmatic terminology is still used by Iranian policymakers to push conservative foreign policy initiatives. Today, rather than export the velayat, Iran’s ideological embrace of revolution centers around its principled opposition to ‘Western imperialism’ and influence in the region. Its more fanatical surrogates may embrace the ideology as it was conceptualized by Khomeini, though this is not mainstream.

While the ultimate framework has changed, empowering revolutionary struggle remains a priority for Tehran, and its primary force of support for revolutionary movements is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force (IRGC-QF). According to the former IRGC commander-in-chief, Major General Mohammad Ali Ja’fari, “the mission of the Quds Force is extraterritorial, to help Islamic movements, expand the Islamic Revolution and to bolster the resistance and endurance of suffering people throughout the world and to people who need help…”[4] Iran’s most longstanding alliances have been built with those who are ideologically similar and often fall along sectarian lines. However, the IRGC-QF has proven to be ideologically flexible as to which groups it backs to oppose the United States.

Iran’s commitment to revolutionary ideology and to the protection of the Muslim world’s downtrodden (as Ja’fari framed it) is foundational to the Islamic Republic’s ethos and to how it develops its foreign policy. By the mid-1980s, Iran was an influential sponsor of armed non-state actors (ANSAs) and revolutionary activity across the globe—running militant training camps and hosting operatives from North Korea, Syria, Palestinian groups, Soviet security agents (KGB), among other organizations and states. The Quds Force even worked closely with Iran’s Foreign Ministry, utilizing its embassies to export the revolution—in both its religious and political conceptions.[5] Through the development of asymmetrical doctrine, warfare education, and training camps, Iran has nurtured revolution and subverted the regional status quo for decades. Its efforts have embraced the notion that “unlike Western military strategy, Islamic warfare [is] rooted in jihad, the holy war which was, by definition, asymmetrical.”[6] The spirit of the Islamic revolution—and the desire to spread it throughout the region—is at the heart of Iran’s foreign policy and is particularly influential in policies regarding its sponsorship of proxies.

Tehran’s policies regarding the support of ANSAs are not only ideologically rooted, but highly pragmatic and a consequence of its geopolitical environment, including its restrictions. Much of Iran’s military equipment (particularly its air force technologies) are pre-1979 American relics from the Pahlavi days. Due to arms embargos and an inability to procure advanced military technology, Iran has become somewhat self-sufficient. Its scientists have reverse-engineered Western robotics, developed pockets of industry—namely producing ballistic missiles—and purchased from foreign sources where available. An eight year-long war with Iraq left its economic and military infrastructure in shambles, while international pressure has made procuring new technologies, as well as selling its own, very difficult.[7] Tehran’s 2014 defense budget was two-thirds that of Abu Dhabi, at $14 billion versus $22.7 billion, and dwarfed entirely by Riyadh’s nearly-$81 billion allocation.[8] Consequently, Iran has responded to its disadvantaged conventional military in Clausewitzian fashion by using other means and political instruments in order to level the playing field.[9] In this case, the “other means” are asymmetrical warfare, and the “political instruments” are proxy militias.

Surrogate Perspectives and Autonomy

As a result of its long-term relationships with proxies, Iran has learned to use a dynamic approach to principal-agent cooperation. To best understand the malleable relationship between Tehran and its surrogates, it is useful to analyze its command style as a variant of authoritative, delegative, and cooperative control. It uses these three types of management differently for different groups, as well as when dealing with a particular group in changing circumstances.

In the example of Hezbollah, Iran displays all three of these sponsorship approaches. Within domestic politics, it has relegated itself to a delegative relationship. This approach is pragmatic and considerate of relevant barriers. Tehran trusts Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, to uphold the ethos of Iranian ideology and to remain a loyal ally. It understands that its sponsorship is necessary to support Hezbollah’s public works projects which keep the group popular and in power. However, Iran equally acknowledges a degree of autonomy that must be granted for the group to flourish within the Lebanese political arena. Once it became clear that an Iranian-modeled Islamic republic was unlikely to take hold in Lebanon, its goals shifted to preserve the greatest influence with the least visibility. Expanding outward to Hezbollah’s role in carrying out armed resistance and exporting revolutionary ideologies, Iran has a more collaborative relationship. The militia’s armed wing works closely with the IRGC-QF to achieve shared goals. Its operations against Israel embody Iranian opposition to Zionism and Western imperialism in the region—a core principle to Khomeini’s revolutionary ideology—while Iran’s support of indigenous rebel groups across the region is consistent with its commitment to uplift the downtrodden in the Islamic community. This collaborative relationship has proven invaluable for Tehran, which is hesitant to deploy its own forces when it can effectively utilize its most trusted and efficient proxy. At times however, Iran must flex its parental muscle and direct surrogates in an authoritative manner, which is observed clearly in Hezbollah’s sustained engagement in the Syrian Civil War. Though the organization’s initial involvement was self-interested, it fights out of loyalty to its sponsor, rather than for its own welfare. In this manner, Iran’s nearly forty year investment in Hezbollah has paid extreme dividends and bought itself a militia that will fight on command.

Iran’s bonds with its other proxies are less enduring, though still more dynamic than most state-sponsor relationships. Even with close ties to the PMF in Iraq, there are limitations to the influence Tehran can exert. Like Hezbollah in Lebanon, Iran has successfully used aligned individuals to penetrate the Iraqi parliament and have sway in its internal politics. However, torn between Western intrusion and Iranian influence, Iraqis have become increasingly suspicious of foreign meddling in their domestic affairs, and today Iran is on the back foot in Iraq. The deaths of Qasem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis have hindered operations in Iraq sizably. Soleimani, who worked directly with the leadership of the PMF for years, even engaging with them in their native Arabic tongue, has been replaced by Major General Esmail Ghaani. The new Iranian commander is less familiar with the Iraqi organizations, lacks personal relationships with the brass, and operates through an interpreter. As a flex of sovereignty, the Iraqi government even required Ghaani to apply for a visa on his second visit to the country as the newly-appointed chief —an unimaginable formality in his predecessor’s time.

In addition to this critical change of leadership, Iran’s financial constraints have taken a toll on its influence in Iraq, due to reimposed sanctions following the American exit from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which acutely affected Iran. On one visit, Ghaani brought PMF leaders silver rings—a symbolic gift in Shi’a Islam, but not the cash its proxies expected or hoped for.[10] The gesture is viewed as an inadvertent distress signal of Iran’s strained cash flow and highlights the already-fraying relationship between Tehran and its Iraqi surrogates. Shiite militias in Iraq have continued to splinter and are increasingly open to taking orders from the Iraqi government rather than Tehran. The deaths of Iran’s gatekeeper, Soleimani, and the PMF unifier, al-Muhandis, have caused this divide to widen. Any delegative power Iran imbues is a product of lacking control, rather than genuine confidence in its Iraqi partners. Its authoritative capacity is limited to the more ideologically radical groups it influences, such as Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq, both of whom have fought on behalf of Iranian interests in foreign conflicts, such as the Syrian Civil War and the 2006 Lebanese-Israeli War. Especially as the change in leadership has negatively affected this dynamic and as popular support in Iraq wanes, Iran’s control of the PMF is best described as collaborative. Tehran buys influence by supporting loyal groups, giving them a fighting and political edge, but must be considerate of the nationalistic trends that exist in Iraq, even among its aligned groups, like the Badr Organization. Nonetheless, Iran appreciates that assets and influence in its backyard are too strategically important to give up easily. While its sway today is less robust than several years ago, Tehran will work to strengthen its strained position in Iraq.

In Gaza, Iran’s sponsorship of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) is a testament to the fundamentally political nature of conflict in the Middle East, rather than the sectarian characterization that is often used (as Palestinian resistance groups are Sunni, not Shi’a). However, the conflict in Syria has complicated Iran’s relationships with its proxies in Gaza. At the outset of the conflict, Tehran expected Hamas to fall in line and aid the group’s longtime supporter and critical Iranian ally. Instead, Hamas snubbed its patron, reluctant to become embroiled in a sectarian conflict it had little stake in. Conversely, PIJ, which has remained fiercely loyal to its sponsor, has received blowback from its supporters for Iran’s role in the Syrian Sunni bloodshed. At the same time, Qatar’s increasingly active role as a mediator in the region presented new opportunities for Hamas. Upsetting the regional status quo, Qatar has not only clashed with Saudi Arabia, but also seeks to overshadow Iran by becoming the arbiter in Gaza. The rise of Doha has certainly come at Tehran’s expense, as exemplified by Iran’s cooling relationship with Hamas. The injection of Qatari cash, distributed to Gazans via Hamas, is seen by many as a vital stimulus for the Strip, and the main reason Hamas is able to retain control. As Hamas is slowly becoming more amenable to brokered mediation, other, more radical, Palestinian groups are on the rise. Thus, Doha’s replacement of Tehran is widely embraced—even by Israel—as a positive geostrategic shift. Qatar’s desire to gain influence in the region has provided Hamas with a significant opportunity, and with the latitude it needs to resist Iranian calls to action. And, as Doha has upstages Tehran in Gaza, Iran loses leverage and its capacity to influence its surrogates. This lack of authoritative control was most evident when Hamas refused Iran’s call to arms in Syria. With PIJ, Iran has a cooperative principle-agent relationship. Its “pay-for-performance” approach to sponsorship provides it with a degree of power, particularly as PIJ fights to assert itself as the more radical faction in the Strip. Concerning Hamas however, Iran lacks control, ultimately having little say in the group’s operations.

Traditional literature portrays states as the final arbiter on proxy relations—able to bully surrogates into doing their bidding, and even willing to pit militias against one another to achieve their goals. In reality, when circumstances are right, surrogate groups have immense leverage in navigating their relationships with sponsor states. As Hamas exemplifies, under certain conditions proxies can dictate the relationship dynamic, move between patrons, and play states against one another. Defying the rote narrative of proxy-sponsor dynamics, surrogates can play political chess with patron states, even positioning them against one another in pursuit of their own greater strategic goals.

In Yemen, political considerations underscore Tehran’s support for the Ansar Allah movement, though both parties readily exploit sectarian rifts to further strategic goals. Houthi acceptance of Iranian sponsorship is a mixed bag of rhetoric and realism. There is little doubt that, as the conflict in Yemen persists and exacerbates, the Houthi-Iranian partnership correspondingly entrenches. The group’s global principles—such as its opposition to the United States and Israel—largely align with Iranian strategic interests and political ideologies. However, despite the ideological reasons for Iranian support of the Ansar Allah movement, the relationship is largely a pragmatic one, with both sides benefiting from the mutual convenience as Iran increases its level of support for the Houthis by way of weapons, funding, training, and fighters. Saudi Arabia views Yemen as its backyard, in the same manner Iran perceives Iraq.[11] To this extent, it is clear why Riyadh has gone to such great lengths to guard its influence in Yemeni affairs. For Tehran, the commitment to Ansar Allah has been minimal and the rewards, maximal. Leveraging Houthi combatants to fight for its greater geostrategic competitive goals in the region—the political opportunity to undermine the Saudi status quo—proved to be the ultimate impetus for Iran’s support of the Shi’a militia.

The original dynamic with Ansar Allah was that of a delegative relationship, primarily because Tehran wished to maintain distance from the face of the conflict. The Islamic Republic initially offered its rhetorical support and supplied some arms which fueled the revolution. As Saudi coalition victories mounted, however, Tehran ratcheted up its support from passive to active. Though Iranian weapons aid Houthi forces, IRGC-QF advisors entangle it in the fight and solidify its patronage. Its relationship with Ansar Allah has grown to be a collaborative one, as Houthi fighters have attacked Saudi and Western targets, while also invoking Iran’s characteristic anti-Israel rhetoric.[12] It is unclear to what extent such operations are semi-autonomous—motivated by Iranian interests—or whether these confrontations are undertaken directly at the behest of Tehran. Ansar Allah has ideological as well as pragmatic reasons for aligning itself with Iran. Iran is now thoroughly embroiled in the Yemeni conflict and its influence over Houthi militias is only growing.

Conclusions and Implications

Iran lacks monolithic control over its proxies and must navigate its relationships with great consideration to the wills and interests of the groups it supports. Surrogate autonomy varies, dependent on internal and external factors, which influence a group’s ability to make demands and operate with independence. As demonstrated by Hamas, under the right conditions, ANSAs can effectively negotiate terms and conditions, and cause states to compete with one another for patron rights, providing the group with operational latitude. For groups like Hezbollah, which are tightly aligned with Iran and its interests, independence is delegated out of trust, rather than an inability to assert control. In Iraq, cooperative relationships wax and wane—influenced by geopolitics, popular opinion, and even by personal relationships—exposing fault lines within the relationships. Some bonds, as seen in Yemen, are partnerships of convenience more than ideology, which leaves both sides vulnerable to power dynamic shifts that are highly dependent on geostrategic considerations. As with most state patrons, Iran can leverage its ‘power of the purse’ to control groups, especially those desperate for support. However, proxies ultimately operate with varying degrees of autonomy, influenced by factors of strength, ideology, and opportunity.

Understanding the nuance of Iran’s surrogate relationships is necessary to effectively prioritize efforts and allocate resources in the strategic competition between the United States and Iran. Washington should invest in exploiting the vulnerabilities of Tehran’s fraying relationships and recognize that far less can be done to sway its steadfast allies. While the United States is still unlikely to win over a group like Hamas, Washington can politically support the group’s current drift from Tehran’s sphere of influence to less radical Arab states more aligned with U.S. interests. American foreign policy initiatives, such as the Abraham Accords, have altered Middle East dynamics, particularly regarding Gaza, Israel, Qatar, and other Arab states.[13] While Qatar is not a signatory to the Accords, it followed in the wave of Muslim nations that warmed relations with Israel subsequently, and the air of economic and political cooperation has shifted out of Palestinian favor. Qatar has maintained its gatekeeper status regarding money flow to Hamas, which provides an opportunity for the United States to leverage political pressure and favor in exchange for more influence over funding to Gaza. For Iran’s more loyal proxies like Hezbollah, the United States can undermine the group’s power, rather than focus on the relationship it holds with Tehran. Politically, undermining the power might look like bolstering parties within Lebanon who oppose Iranian influence in Beirut, however, so long as Hezbollah serves as a core social infrastructure provider in Lebanon, the group will maintain positive political influence. To this end, the United States should focus on Western-backed social programs that drive favor away from Hezbollah and toward Western spheres of influence. This strategy is long and arduous, but it targets the core of Hezbollah’s populist strength and does so through development rather than an arms race. Militarily, the United States should continue to support targeting Iranian logistic chains that funnel weapons to Hezbollah. These strikes are largely carried out by Israel –– reaffirming the need for American bipartisan political support for Jerusalem’s foreign policy strategies. In Iraq, U.S. intervention has hardly catered favor for Washington. U.S. strategists should capitalize on political discontent with Iranian meddling, while also minimizing the Western footprint, which caused many Iraqis to seek out Iranian support in the first place. After two decades in Iraq, a removed approach to American involvement allows Iraqi resentment of Tehran’s heavy-handedness to organically grow. Similar to Lebanon, the United States should subtly support political parties in opposition to PMF politicians and warlords. Regarding Houthi rebels, American strategy must be more reserved due to the particularly gruesome nature of the conflict. More than other relationships analyzed in this piece, policy considerations should be treated with the utmost scrutiny when deciding how and to what degree support should be provided to allies embroiled in the chaos. While support for Saudi operations in Yemen may ultimately undermine Tehran, the humanitarian repercussions are steep, may prove more hurtful to overall American interests, and outweigh the benefits of a Houthi-Iranian defeat.

Iran’s willingness to exploit regional conflicts in vulnerable states to further its expansionist ambitions and deepen its ‘strategic depth’ (‘omq-e rahbordi’) has sullied its liberator persona and perhaps even undermined its larger foreign policy goals.[14] The growing perception of Iranian imperialism in the region—and the negative consequences this has had on its image—is nothing short of ironic. Opposition to imperialism is one of the Islamic Republic’s core tenets and a vital component of its revolutionary ideology. Meanwhile, Tehran tries to navigate the shifting geopolitical landscape by filling voids, capitalizing on power vacuums, and feeding chaos where necessary. U.S. policymakers should ride the wave of anti-Iranian sentiment as Tehran’s surrogate relationships weaken. As Iran is increasingly viewed, at home and abroad, as the very meddler it abhors, the regime may be forced to reevaluate its foreign policy strategy, particularly regarding its involvement in a myriad of foreign conflicts through its network of proxy militias.

Michael earned his master’s degree in International Relations and Politics from the University of Cambridge before joining the Security and Strategy Seminar as a fellow analyzing U.S.-Iran and later U.S.-Russia strategic competition. His academic research has focused on global armed non-state actors, proxy-sponsor relationships, and their diverse networks of funding. He currently serves as Chief of Staff at a U.S.-based technology startup.

_________________

Image: Tehran, Iran, 30 June 2011, from flickr.com. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tehran,_Iran,_15_53.jpg, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, “Strategic Depth, Counterinsurgency, and the Logic of Sectarianization: The Islamic Republic of Iran’s Security Doctrine and Its Regional Implications,” in Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East, ed. Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel (London: Hurst & Company, 2017), 183.

[2] International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East, 1st ed. (Routledge, 2020), chap. 1, 11-38.

[3] Daniel Byman, Deadly Connections: States That Sponsor Terrorism (Cambridge University Press, 2007), 93; International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East, 11-38

[4] International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East, 11-38.

[5] Matthew Levitt, “Hamas: Politics, Charity, and Terrorism in the Service of Jihad,” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 77-167; Ofira Seliktar and Farhad Rezaei, “Iran, Revolution, and Proxy Wars,” Middle East Today (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 16–17, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29418-2.

[6] Ofira Seliktar and Farhad Rezaei, “Iran, Revolution, and Proxy Wars, Middle East Today,” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 11, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29418-2.

[7] International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East, 11-38; Paul Iddon, “Will Iran Modernize Its Military If UN Arms Embargo Lifted?,” Rudaw, 24 November 2019, https://www.rudaw.net/english/analysis/24112019?fbclid=IwAR1ElXIp9V2sI80ogXpokk4ebhju98kv6W0NRtjDE4fWBkSu0MVcdWutkaw.

[8] Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, “Strategic Depth, Counterinsurgency, and the Logic of Sectarianization: The Islamic Republic of Iran’s Security Doctrine and Its Regional Implications,” 64-165.

[9] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. Michael Eliot Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton University Press, 1989), 87, https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691018546/on-war; Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, “Strategic Depth, Counterinsurgency, and the Logic of Sectarianization: The Islamic Republic of Iran’s Security Doctrine and Its Regional Implications,” 165.

[10] Qassim Abdul-Zahra And Samya Kullab “Troubled Iran Struggles to Maintain Sway Over Iraq Militias,” Associated Presss, 11 June 2020, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-ap-top-news-iran-iraq-virus-outbreak-afde374dca8886517b224bdc18942f1c; Reuters Staff, “Coronavirus and Sanctions Hit Iran’s Support of Proxies in Iraq,” Reuters, 2 July 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-iraq-proxies-insight/coronavirus-and-sanctions-hit-irans-support-of-proxies-in-iraq-idUSKBN2432EY.

[11] Dina Esfandiary and Ariane M. Tabatabai, “Defusing the Iran-Saudi Powder Keg,” Lawfare (blog), 29 May 2017, https://www.lawfareblog.com/defusing-iran-saudi-powder-keg.

[12] Jerusalem Post Staff, “Houthi Rebels Threaten Israel in Statements to Arab Media,” The Jerusalem Post, 10 December 2019, https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Houthi-rebels-threaten-Israel-in-statements-to-Arab-media-610419.

[13] Yoel Guzansky and Yohanan Tzoreff, “Gaza, Qatar, and the UAE: The Abraham Accords After Operation Guardian of the Walls,” The Washington Institute, accessed 23 June 2022, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/gaza-qatar-and-uae-abraham-accords-after-operation-guardian-walls.

14] Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, “Strategic Depth, Counterinsurgency, and the Logic of Sectarianization: The Islamic Republic of Iran’s Security Doctrine and Its Regional Implications,” 164.

[15] Table – Proxy Militia Networks Operating in Iraq: András Derzsi-Horváth, Erica Gaston, and Bahra Saleh, “Who’s Who: Quick Facts About Local and Sub-State Forces,” Iraq After ISIL (Global Public Policy Institute, 16 August 2017), https://www.gppi.net/2017/08/16/quick-facts-about-local-and-sub-state-forces.