During the Cold War, developing countries watched the United States benefit from four-and-a-half decades of technological productivity, economic cooperation with Western Europe, and a consensus over major foreign policy objectives. Today’s race for geopolitical superiority, however, looks radically different. Middle powers will refuse to choose between the United States and its principal adversaries; rather, they will seek independent roles to shape the contemporary world order. In doing so, they will reject the idea of a new Cold War advanced by certain academics and policymakers in response to China’s unprecedented military and economic expansion. [1] [2] Indeed, in February 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden summarized the global situation as “an inflection point between those who argue that…autocracy is the best way forward…and those who understand that democracy is essential.” [3] Washington is once again poised to use a dichotomous framework to advance its foreign policy goals: bipartisan defense spending has increased, partnerships with like-minded allies have prospered, and U.S. intelligence agencies have restructured their focus around the adversaries that challenge American interests. This time, though, winning middle powers’ allegiance will be a much more formidable task. Key non-aligned countries attracted by the prospect of a multipolar world have no desire to see themselves placed on a binary spectrum between the United States and China whereby they have to pick a side in a second Cold War.

In 2010, the Obama administration pioneered a “pivot to Asia” to increase American leadership in a region that had previously been neglected despite its geopolitical significance. [4] Since then, the United States has reinforced its involvement in Asia’s economic and political affairs with a particular focus on the Indo-Pacific. As stated by the 2022 National Security Strategy, “trade with the Indo-Pacific supports more than three million American jobs and is the source of nearly $900 billion in foreign direct investment in the United States.” [5] In addition to its commercial and strategic value, the region harbors some of Washington’s most reliable allies. To that end, the Biden administration spearheaded the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) as a multilateral initiative to support free trade, technological progress, and shared environmental goals. [6] It has also taken steps toward brokering arms deals with Taiwan, furthering subsea cable construction in the Pacific by partnering with Australia and Japan, and increasing investments in Southeast Asia. [7] [8] [9] Simultaneously, though, China is following a similar blueprint. During the last two decades, it has provided a record number of infrastructure, telecommunications, and digital governance loans to Central and Southeast Asian countries. [10] Through the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has stepped up its foreign direct investment in neighboring countries, acquired ownership of Asian energy and transportation companies, and promoted positive relations with Asian governments. [11] Heightened tension between the United States and China stemming from the latter’s ambitions to displace Washington’s financial supremacy in the current world order looms large over each country’s parallel investments in Asia. [12] Although U.S. President Joe Biden explicitly rejected the notion that the two countries are in a new Cold War after meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, the urge to draw comparisons to the 20th century bloodless standoff with the Soviet Union will prove irresistible for American policymakers and foreign policy experts seeking to inject a sense of urgency into governmental decisions. [13] However, this risks alienating non-aligned countries who prioritize their national interest over participation in an ideological competition.

Exercising caution when describing the current rivalry with China is especially important when communicating with countries that the United States views as dependable. Australia, India, and the Philippines are three examples of states enjoying close ties with Washington, but which have each made their own statements about the priority they afford to the concept of national interest. Australia, a U.S. treaty ally typically viewed as categorically supportive in the struggle against Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific, has a much more nuanced position than it initially seems. Within six weeks of her time as Australian Foreign Minister, Penny Wong declared that Australian affairs should be “more than just supporting players in a grand drama of global geopolitics.” [14] Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar gave voice to a similar sentiment in 2020 when he commented that New Delhi must pursue policies in its own interest without automatically gravitating to Washington’s side because of Beijing’s increasing bellicosity. [15] The recently elected president of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., stated that an “independent foreign policy, with the national interest as our primordial guide,” will steer the country in the decades to come. [16] These three leaders’ statements all embody an important trend defining states’ conduct in the 21st century: a desire for multipolarity and flexible non-alignment. Unwilling to return to a dichotomous international environment whereby smaller states’ economies depend largely on the decisions pursued by two great titans, today’s middle powers are using their neutrality as a diplomatic bargaining tool. Consequently, American policymakers should avoid jumping to conclusions about a regime’s allegiance after it engages with one of Washington’s adversaries. Meetings held between China and countries like Thailand, India, and the Philippines do not indicate that the United States has lost all influence in the region. In fact, Washington should view them as unparalleled learning experiences. Tracking the concerns expressed by non-aligned leaders and even U.S. treaty allies during summits with American adversaries allows agents and policymakers to know what areas they should prioritize when dealing with these countries. From there, the U.S. president and the Secretary of State can communicate how the United States is addressing these concerns so that non-aligned states see that cooperating with Washington is in their best interest.

In June 2022, the United States and Thailand signed a “Communiqué on Strategic Alliance and Partnership” highlighting common areas of interest, including cybersecurity, climate change, and free commerce in the Indo-Pacific. [17] A few days earlier, Thailand’s prime minister invited and met with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to laud Beijing’s commitment to international development and fighting poverty. [18] In November 2022, during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit, Chinese leader Xi Jinping was warmly welcomed by Thailand’s prime minister and several high-ranking officials to inaugurate the start of the conference. [19] At the same reunion, though, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris worked to strengthen ties with the country. [20] [21] Thailand, which shifted its foreign policy objectives in the 1980s from the crisis in Cambodia to the development of its “regional economic power,” benefits more from a world in which it can draw from both Washington and Beijing’s strengths. [22] The United States must recognize that such oscillations are in non-aligned states’ interests and accordingly tailor its discourse to them.

The Philippines tested how far Washington’s patience can go by applying Thailand’s approach to an extreme degree. If the U.S. Department of State or Defense would have taken every one of Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte’s words at face value in 2016 – such as when he stated that “America has lost… I’ve realigned myself in [China’s] ideological flow, and maybe I will also go to Russia to talk to Putin” – then they may have pursued an overly aggressive policy when the Philippines would, in fact, gravitate back to the United States a few years later. [23] [24] The Trump administration correctly handled Duterte’s capriciousness by not reciprocating his behavior. American policymakers can get a better sense of which proclamations made by foreign leaders are disingenuous or exaggerated by calculating what is in the state’s national interest. With respect to the Philippines, remittances sent from American homes to Manila, the population’s exceptionally favorable view of the United States, and long-standing military cooperation made separation a sense- less endeavor. The same idea of prioritizing national interest during talks with other countries holds true for India. Although New Delhi’s attitude toward China is less ambivalent than Thailand’s and the Philippines’s, Washington has nonetheless had to exercise patience concerning India’s economic and energy-based ties with Moscow. In the months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, American policymakers struggled to understand that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s refusal to condemn the Kremlin was not a sign that he was prepared to abandon the rules-based international order in favor of a world where sovereignty holds no meaning [25]. Nevertheless, the U.S. Department of State eventually took a much more strategic approach – one that precisely seeks to alter India’s calculation of what lies in its national interest – by engaging in high-level talks with Indian officials about reducing dependence on Russian arms and energy exports [26]. Thailand, the Philippines, and India highlighted the importance of making a deliberate effort to maintain strong relations with non-aligned countries even when they pursue policies that signal a desire to detach from the United States.

Tracking what aligns with a state’s national interest and what guarantees can be extended to bring that state more fully into the U.S.-led international order must not become a purely reactive exercise. Instead, the United States must determine the major preoccupations affecting a country before they are widely dispersed in international settings. This proactive aid encourages foreign governments to develop warmer relations with Washington because they determine that relying on American aid is in their national interest. For this process to work, it is indispensable for Foreign Service Officers, intelligence agents, and military personnel to equip themselves with cultural, linguistic, and historical expertise in particular regions. Only by interacting with citizens on the ground, verifying the narratives diffused by media groups across the world, and tracing how tensions concretely develop in a given state will the United States anticipate the issues that leaders will raise when they meet with their American counterparts. When opportunities for foreign travel are limited, diplomatic and intelligence agencies should recruit candidates who have participated in immersion programs, taken cultural classes stemming beyond national security, or forged bonds with individuals who have spent a significant amount of time in a foreign country. A critical qualification for selecting and training Americans in the field of national security is their rejection of a Manichean worldview. This has been an especially difficult challenge when managing Washington’s relations with countries that share a willingness to monitor or curb China’s vertiginous economic and military expansion.

India is a case in point. In 2021, after India purchased the S-400 missile defense system from Russia, Kenneth Juster ended his four-year term as American envoy to New Delhi with a prophetic address. “We haven’t hit that point yet but [soon]… India has to decide how much it matters to get the most sophisticated technology,” he said. [27] A year later, India reached “that point” when Russia invaded Ukraine. New Delhi continued to buy Russian defense technologies because it had already committed to arms exchange deals, its existing weapons systems need to be serviced and upgraded by the Russian companies that sold them in the first place, and Western technologies are more expensive. [28] U.S. military and intelligence agencies did not move fast enough to offer cheaper alternatives that would wean New Delhi off its attachment to the Kremlin. As a result, Washington now faces a Russian state more capable of filling its treasury because it can sell cheap parts and honor existing contracts with India. In October 2000, Russia and India forged a $3 billion weapons deal that set the stage for the cooperation that has persisted in spite of Moscow’s war in Ukraine. [29] At the same time, though, India has proved itself to be a reliable partner in opposing Chinese expansion in Asia. This is why high-level discussions whereby the U.S. Department of State offers India alternatives to Russian gas and arms exports are so valuable. New Delhi, hoping to profit from a more multipolar world, will resist cooperating with the United States if it insists that India must immediately abandon all ties with Russia in the name of a U.S.-led rules-based order. The conversation between Washington and New Delhi must be about how the latter’s long-term national interest lies in detaching from an erratic power bent on undermining norms of territorial sovereignty and international law. The Biden administration has acted in this spirit by accepting Modi’s insouciance regarding Russia’s invasion while highlighting the urgency of Putin’s nuclear threats to encourage a separation between New Delhi and Moscow.

In the decades to come, national interest rather than allegiance to a great power will be the guiding principle behind many countries’ foreign policy. Countries like India, Thailand, and the Philippines will refuse to be associated with overarching terms like “the West” or a “Sino-Russian bloc” since they benefit from the flexibility of non-alignment. The United States will have to remain alert to these states’ needs and desires as it leverages its own vast array of domestic natural resources to demonstrate to rising powers that it is in their interest to participate in a U.S.-led international order rather than the revisionist system that China and Russia have begun developing. The Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. Department of State can lead the way. It should expand its regular planning talks to countries like Thailand and the Philippines while making the dialogue about national interest. As a liaison between the department’s regional bureaus and U.S. government agencies, Policy Planning can ensure that officials who frame discussions with foreign leaders in terms of their national interest are in close communication with American policymakers to produce a coordinated grand strategy.

Axel de Vernou ’25 serves as the Officer of Communications for the AHS chapter at Yale University, where he is majoring in Global Affairs and History.

—

Notes:

[1] Ana Swanson, “Trump’s Trade War With China Is Officially Underway,” The New York Times, 5 July 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/business/china-us-trade-war-trump-tariffs.html.

[2] Yukon Huang, “The U.S.-China Trade War Has Become a Cold War,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 16 September 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/09/16/u.s.-china-trade-war-has-become-cold-war-pub-85352.

[3] Sam Roggeveen, “Democracy vs Autocracy: Biden’s ‘Inflection Point,’” Lowy Institute, 23 February 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/democracy-vs-autocracy-biden-s-inflection-point.

[4] Kenneth Lieberthal, “The American Pivot to Asia,” Brookings Institution, 21 December 2011, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-american-pivot-to-asia/.

[5] The White House, “In Asia, President Biden and a Dozen Indo-Pacific Partners Launch the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity [Fact Sheet],” 8 July 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/23/fact-sheet-in-asia-president-biden-and-a-dozen-indo-pacific-partners-launch-the-indo-pacific-economic-framework-for-prosperity/.

[6] The White House, “In Asia.”

[7] Anthony Capaccio, Samson Ellis, and Daniel Flatley, “Biden Administration Preps $1.1 Billion Arms Sale to Taiwan,” Bloomberg News, 29 August 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-08-30/biden-administration-readies-1-1-billion-ams-sale-to-taiwan.

[8] The White House, “United States-Australia-Japan Joint Statement on Cooperation on Telecommunications Financing,” 15 November 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/11/15/united-states-australia-japan-joint-statement-on-cooperation-on-telecommunications-financing/.

[9] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “America set to invest $150 million in Southeast Asia,” 15 May 2022, Economic Times, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/america-set-to-invest-150-million-in-southeast-asia/articleshow/91570820.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst.

[10] Bart Hogeveen, et. al, ICT for Development in the Pacific Islands (Canberra, Australia: Australian Strategic Policy Institute, February 2022), https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/ad-aspi/2020-02/ICT%20for%20development%20in%20the%20Pacific%20islands.pdf?x_oS.r8OVVfTlxxgNHI58k_VL45KC83H.

[11] Manjari Chatterjee Miller, China and the Belt and Road Initiative in South Asia (New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, June 2022), 3-4, https://cdn.cfr.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/Miller-ChinaBRISouthAsia.pdf?_gl=1*1ichmoa*_ga*MTE0NDcyMzExNS4xNjcyMDY4NzA0*_ga_24W5E70YKH*MTY3MjE5NDc0OC4yLjAuMTY3MjE5NDc0OC4wLjAuMA.

[12] Eustance Huang, “China’s digital yuan could challenge the dollar in international trade this decade, fintech expert predicts,” CNBC, 15 March 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/15/can-chinas-digital-yuan-reduce-the-dollars-use-in-international-trade.html.

[13] Christina Wilkie, “Biden sees no need for ‘a new Cold War’ with China after three-hour meeting with Xi Jinping,” CNBC, 14 November 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/11/14/biden-sees-no-need-for-a-new-cold-war-with-china-after-three-hour-meeting-with-xi-jinping.html.

[14] Penny Wong, “National Statement to the UN General Assembly, New York,” Minister for Foreign Affairs, 23 September 2022, https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/penny-wong/speech/national-statement-un-general-assembly-new-york.

[15] Atman Trivedi, “India Doesn’t Want to Be a Pawn in a U.S.-China Great Game,” Foreign Policy, 7 August 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/08/07/india-doesnt-want-to-be-a-pawn-in-a-u-s-china-great-game/.

[16] Riyaz ul Khaliq, “National Interest Paramount, Says Philippines’ Marcos on Foreign Policy,” Anadolu Agency, 25 July 2022, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/national-interest-paramount-says-philippines-marcos-on-foreign-policy/2645214.

[17] U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Thailand, “United States-Thailand Communiqué on Strategic Alliance and Partnership,” 10 July 2022, https://th.usembassy.gov/united-states-thailand-communique-on-strategic-alliance-and-partnership/.

[18] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha Meets with Wang Yi,” 5 July 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202207/t20220706_10716196.html.

[19] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “President Xi Jinping Arrives in Bangkok to Attend the 29th APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting and Visit Thailand,” 17 November 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202211/t20221117_10977144.html.

[20] Antony Blinken, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken At the Handover of the APEC Ministerial Meeting to the United States,” U.S. Department of State, 17 November 2022, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-the-handover-of-the-apec-ministerial-meeting-to-the-united-states/.

[21] The White House, “Readout of Vice President Kamala Harris’s Meeting with Indo-Pacific Leaders on DPRK’s Ballistic Missile Launch,” 18 November 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/11/18/readout-of-vice-president-kamala-harriss-meeting-with-indo-pacific-leaders-on-dprks-ballistic-missile-launch/.

[22] Leszek Buszynski, “Thailand’s Foreign Policy: Management of a Regional Vision,” Asian Survey (1994) 34 (8): 723, https://doi.org/10.2307/2645260.

[23] Jane Perlez, “Rodrigo Duterte and Xi Jinping Agree to Reopen South China Sea Talks,” The New York Times, 20 October 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/21/world/asia/rodrigo-duterte-philippines-china-xi-jinping.html.

[24] Derek Grossman, “Duterte’s Dalliance with China Is Over,” RAND Corporation, 2 November 2021, https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/11/dutertes-dalliance-with-china-is-over.html.

[25] Derek Grossman, “India’s Maddening Russia Policy Isn’t as Bad as Washington Thinks,” Foreign Policy, 9 December 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/09/india-russia-ukraine-war-putin-modi-biden-sanctions-geopolitics/.

[26] Jennifer Hansler et al., “US in talks with India about rethinking reliance on Russian arms and energy,” CNN, 21 September 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/21/india/india-us-talks-shifting-russia-reliance-intl-hnk/index.html.

[27] “India May Have To Make Choices In Arms Deal Approach: Outgoing US Envoy Kenneth Juster,” Outlook, 6 January 2021, https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/world-news-india-must-keep-in-mind-variables-of-military-hardware-acquisition-american-envoy-kenneth-juster/369616.

[28] Krzysztof Iwanek, “Indian Experts Want New Delhi to Buy Fewer Arms From Russia (and Everyone Else, Too),” The Diplomat, 27 June 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/06/indian-experts-want-new-delhi-to-buy-fewer-arms-from-russia-and-everyone-else-too/.

[29] Jyotsna Bakshi, “India-Russia Defence Co-operation,” Strategic Analysis 30, no. 2 (Apr-Jun 2006): 451, https://www.idsa.in/system/files/strategicanalysis_jbakshi_0606.pdf.

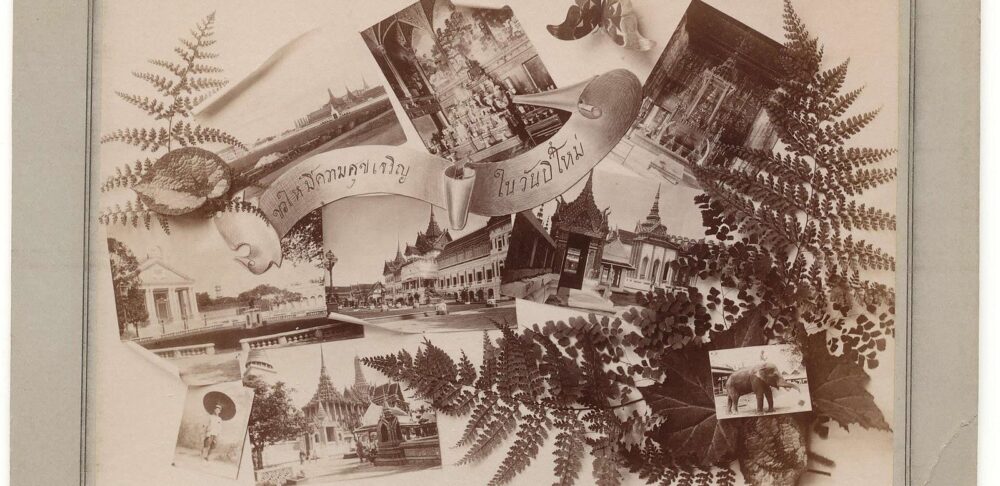

Image: “New Year card/Nyttårspostkort fra Siam (Thailand) 1894,” by Riksarkivet (National Archives of Norway), retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Siam-Thailand-1894.jpg. This image was taken from Flickr’s The Commons. The up- loading organization may have various reasons for determining that no known copyright restrictions exist, such as: The copyright is in the public domain because it has expired; The copyright was injected into the public domain for other reasons, such as failure to adhere to required formalities or conditions; The institution owns the copyright but is not interested in exercising control; or The institution has legal rights sufficient to authorize others to use the work without restrictions.