International politics today is a source of anxiety and uncertainty. China’s rise to power and corresponding ambitions signals a return of great power competition, threatening the peace and stability of the American-led international order. To meet this moment, the American foreign policy community must first address a problem at the core of its field: the relative dearth of historical and philosophical analysis in international relations scholarship. Academics and policymakers alike should revisit the tradition of classical realism and use its insights to guide their policy recommendations and decision-making.

Classical realism, centering on the writings of Thucydides, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, and Hans J. Morgenthau, is guided by the study of human nature as witnessed in history. Morgenthau writes that the “root of conflict and concomitant evil stems from the animus dominandi, the desire for power. This lust for power manifests itself as the desire to maintain the range of one’s own person in conflict with others, to increase it, or to demonstrate it.” [1] Two thousand years before Morgenthau, Thucydides offers a similar analysis. In his “Melian Dialogue,” the Athenians represent the deep human desire to exercise power over others: “Of the gods we believe and of men we know, that by a necessary law of their nature they rule wherever they can.” [2] This desire for power to rule wherever one can – animus dominandi – leads statesmen to seek domination over foreign states.

Though classical realism does not offer a set of policy prescriptions for statesmen, its account of human nature offers a way to interpret international relations that can guide decision making. Some realist statesmen, such as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, have used this lens to suggest that policymakers seek an equilibrium among the great powers. The balance of power approach to international politics attempts to wrestle and subdue the animus dominandi found in human nature. If statesmen believe that they cannot succeed in a war with others, they will likely avoid conflict. Thus, classical realists think that if statesmen create an order in which no single country or coalition of countries are capable of dominating others, global stability can be achieved.

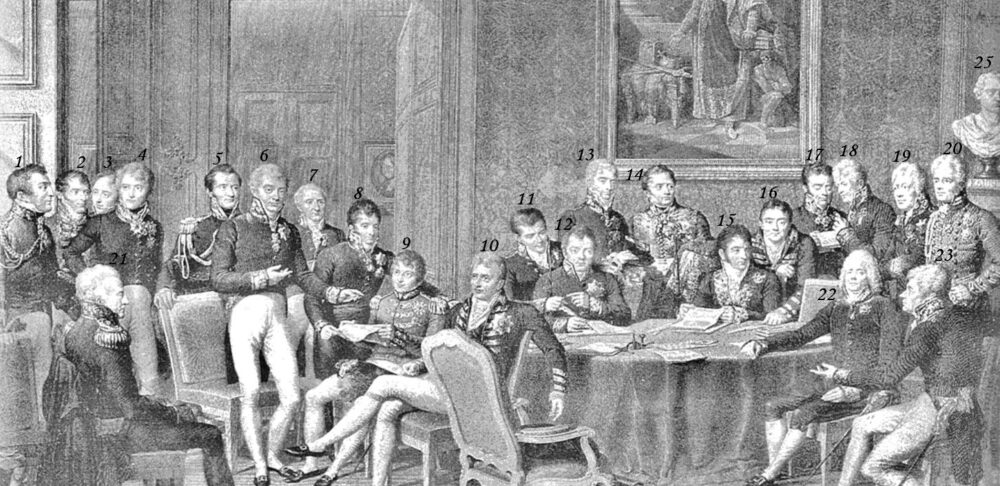

Historical examples illustrate the benefits of classical realist thinking on the balance of power. Following the Napoleonic Wars, the European powers saw the necessity in establishing an order to prevent another disastrous conflict from breaking out. Klemens von Metternich of Austria and Robert Stewart, Lord Castlereagh, of Great Britain used the balance of power to realize this goal. At the Congress of Vienna, Prussia sought to increase its control over Germany while Russia desired control over Poland. Metternich and Castlereagh feared the resulting imbalance of power if these countries had their way. Accordingly, the two statesmen negotiated to limit Russian and Prussian power: Metternich and Castlereagh combined with their recent French adversary to present a united front in negotiating a territorial settlement. [3] These statesmen’s concern for balance ushered in relative peace and stability for a generation.

Other classical realists, however, contend that statesmen should not actively attempt to create an equilibrium. Morgenthau believed doing so would be dangerous: “All nations actively engaged in the struggle for power must actually aim not at a balance – that is, equality – of power, but at superiority of power on their own behalf. And since no nation can foresee how large its miscalculations will turn out to be, all nations must actively seek the maximum of power obtainable under the circumstances.” [4] Morgenthau understood the fallibility of human beings; statesmen may err in their judgment in pursuing a balance of power, thereby endangering their countries. As a result, states must prudently maximize their own power. Pursuing one’s national interest has gone by many names throughout history: raison d’état and realpolitik are but two examples. This strategy in international relations begins with the premise that if all people naturally seek power over others, then all politics is a struggle for power. [5] So, to combat others’ domineering ambitions, statesmen must pursue their national interests. After all, “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” [6]

The prudence of this approach is also illustrated by history. At the outset of the seventeenth century, Europe was plunged into a continent-wide war. Subsequent to the Protestant Reformation, many of the German principalities within the Holy Roman Empire left the Catholic Church in favor of the new Protestant creed. This led to the Thirty Years’ War. On one side of the conflict were the Protestant German principalities and their allies; on the other, were the Hapsburgs and their Catholic allies. Meanwhile Cardinal Richelieu of France recognized that the Hapsburgs were nearing hegemony in Europe. If France, a Catholic nation, fought alongside its ideological allies, it would ensure the Hapsburgs’ supremacy over Europe. In the name of France’s national interest – its raison d’état – Richelieu ignored ideological pressures and joined the Protestant coalition instead. [7] His decision averted Hapsburg hegemony, pushed the Holy Roman Empire into decline, and helped France become Europe’s leading power.

The classical realist approach, unfortunately, is not employed in international relations today. By the twentieth century, behaviorism and positivism won over academics and policymakers alike. The twentieth-century behavioral revolution encouraged a belief that human reason and the scientific method would allow the social world to be studied in the same way as the natural world. As such, contemporary scholars reformulated international relations to remove philosophical questions about human nature, instead seeking to predict and explain state behaviors on empirical grounds. With that, the statesman was recast as a rational political engineer, and the field of study was transformed from a tragic art into a natural science, cutting the humanities out of a deeply human practice.

Neorealism emerged on the academic scene in the latter half of the twentieth century as a way of making realism appear more scientific. Deviating from the classical approach, neorealists do not begin with an analysis of human nature. Instead, neorealists hold that the anarchical structure of the world explains international relations: without a global police force, individual states are required to seek power to protect themselves. To defensive realists – like Kenneth Waltz – all states balance power against stronger states as a means of protecting themselves. [8] To offensive realists – like John Mearsheimer – all states seek to ensure their security by pursuing hegemony. [9]

The weakness of neorealism is its removal of human agency. Its scientific approach suggests a predictable model: the structure of the international arena causes states to respond to the pressures of a changing world. In other words, it assumes political engineers automatically pull the correct levers and push the right buttons that follow the neorealist paradigm — to balance and maximize power as a means of survival. It is an elegant theory, but unhappily it is also clearer than the truth. World politics cannot be sufficiently predicted for neorealism’s theoretical requirements. There are too many variables that extend beyond statesmen’s control. Classical realists recognize this. They believe that “genius” statesmen possess certain leadership qualities – like prudence and ingenuity – that allow them to manage chance and fortune. Cardinal Richelieu, for instance, showed prudence and ingenuity in joining the Protestant coalition against the Hapsburgs. Over a century later, Metternich and Castlereagh’s ingenuity helped them craft a stable world order by marrying tradition to innovation. These statesmen’s flexiblity allowed them to develop pragmatic foreign policies that influenced the course of history. Despite this, neorealism dismisses the agency of statesmen.

Moreover, the inadequacy of neorealism lies in its inability to consider the difference between status quo and revisionist powers. [10][11][12] In articulating that all states seek power as a means for survival rather than ambition, neorealists like Waltz imply that states only seek the power necessary for their survival. However, the continued existence of the state alone cannot adequately explain a revolutionary power’s motivation, as their ambitions may pose an existential threat. Neorealist theory, therefore, develops “a world of all cops and no robbers.” [13] On the other hand, classical realists recognize this key distinction. They maintain that some countries believe it necessary to preserve the current world order; just as others seek to construct new political orders. [14] [15] [16] China’s desire to overturn American regional hegemony in Asia – and perhaps in the rest of the world – shows its position as a revisionist power.

Along with neorealism, the theory of neoliberalism guides contemporary international relations. The neoliberal school of thought is built on the premise that the world is improvable through reason. Drawing on inspiration from Enlightenment-era thinkers, Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye formulated the theory of complex interdependence. If states tie their economies together, neoliberals predict that states would be incentivized to cooperate with each other. After all, conflict and war would only impair their own economies. [17] Thus, the neoliberal view suggests that the world would become more peaceful through a globalized economy.

But neoliberals, unlike classical realists, do not sufficiently appreciate that we are also driven by irrational impulses. So, the rational desire to preserve one’s economic capabilities cannot act as a bulwark against the tragedy resulting from the animus dominandi. After all, “fear, honor, and interest” all drive a statesman’s decisions. [18]

No period in history better demonstrates this reality than the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1909, Norman Angell first published The Great Illusion, arguing that the interconnected European economies made war between nations futile. [19] A few years later, the European nations marched into Armageddon. Witness the scene in Austria in August 1914:

In every station placards had been put up announcing general mobilization. The trains were filled with fresh recruits, banners were flying, music sounded, and in Vienna I found the entire city in a tumult … There were parades in the street, flags, ribbons, and music burst forth everywhere, young recruits were marching triumphantly, their faces lighting up at the cheering. [20]

The fear of each other and desire for glory led Europeans to turn against their material interests and turn towards war.

Neorealism and neoliberalism, despite their shortcomings, guide much of American policymaking today. Flawed theories yield flawed policies with likely dangerous consequences. It is crucial to restore classical realism to contemporary policy discourse.

International relations are, first and foremost, a tragic art, not a science. So, our world needs fewer rational policy engineers and more statesmen studied in history and philosophy. [21] From Thucydides, we can learn about the origin of conflict; from Machiavelli and Kautilya, we can learn about statesmanship; from Hobbes, we can learn about the nature of power politics; from Sun Tzu and Karl von Clausewitz, we can learn about military strategy. These thinkers cannot (and will not) give us a ten-step program to secure the United States and promote its interests. But they make formative claims about human nature and the human experience that remain relevant today.

Consequently, drawing on these traditions of classical realism that are rooted in a deep understanding of human nature can help statesmen craft policies to promote American interests. Specifically, the increased tensions between the United States and China suggest the return of great power rivalry. To avert the perils of Sino-American war, today’s practitioners should look to Metternich and Castlereagh’s example and build a regional balance of power in Asia. For instance, the United States could develop an anti-hegemonic coalition of states – such as India, Australia, Japan, Vietnam, and others – that rivals China’s bloc. [22] An equal distribution of regional power between the two great powers would dissuade them from engaging in a hegemonic war. Furthermore, there is a lesson to be learned from Richelieu’s strategy: to prevail in competition with China, American policymakers should put aside their ideological preferences to embrace policies that maximize American power. Washington should not hesitate to build strategic partnerships with countries of other regime types in Asia, or to resolve existing disputes with nations that could become valuable partners in a coalition to contain China.

It is time for scholars and statesmen to end the era of “scientification” and return to the study of history and philosophy nurtured by classical realism. After all, “politics, like society in general, is governed by objective laws that have their roots in human nature. In order to improve society, it is first necessary to understand the laws by which society lives.” [23] If politics are governed by men, and if men are governed by nature, then we must embark on a voyage to uncover our nature. After scholars and statesmen resume that intellectual journey, international relations come closer to finding its identity.

David Brostoff ’24 is the President of the AHS chapter at American University’s School of International Service, where he is an international relations major, a Russian minor, and a Lincoln Scholar in political theory.

—

Notes:

[1] Hans J. Morgenthau, Scientific Man vs. Power Politics (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1946), 192.

[2] Thucydides, Landmark Thucydides, ed. Robert B. Strassler (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 354.

[3] Henry A. Kissinger, A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812-22 (Echo Point Books & Media, LLC, 2013), 158-171.

[4] Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, ed. Kenneth W. Thompson, 5th ed. (New York, NY: Knopf, 1985), 210.

[5] Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations, 29.

[6] Thucydides, 352.

[7] Henry A. Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 59.

[8] Kenneth Waltz, Man, the State and War: A Theoretical Analysis (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1959), 60.

[9] John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2001), 32-33.

[10] Edward Hallett Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 1919-1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations (New York, NY: Perennial, 2001), 82-83.

[11] Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations, 43.

[12] Kissinger, A World Restored, 2.

[13] Randall L. Schweller, “Neorealism’s status-quo bias: What security dilemma?,” Security Studies 5, no.3, 1996, 90-121, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636419608429277, 91-92.

[14] Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations, 57.

[15] Kissinger, A World Restored, 3.

[16] Carr, 83-84.

[17] Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, “Power and Interdependence,” Survival 15, no. 4, 1973, 158-165, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396337308441409.

[18] Thucydides, 45.

[19] Ali Wyne, “Disillusioned by the Great Illusion: The Outbreak of Great War,” War on the Rocks, 2 February 2014, https://warontherocks.com/2014/01/disillusioned-by-the-great-illusion -the-outbreak-of-great-war/.

[20] Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday, trans. Anthea Bell (London: Pushkin Press, 2014), 222-223.

[21] Morgenthau, Scientific Man, 10.

[22] Elbridge A. Colby, The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), 40-45.

[23] Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations, 4.

Image: “Vienna Congress,” by Jan Losenicky, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_histories_of_Herodotus_(1904)_(14756627536).jpg. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 70 years or fewer.