On June 26, 1963, President John F. Kennedy boasted, “All — All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin.” This extraordinary line in his Ich bin ein Berliner speech rested on a conviction that the American people “take the greatest pride, that they have been able to share … the story of the last 18 years” with the people of West Berlin. [1] It was also a veiled threat: the United States, the leader of the free world, was prepared to defend West Berlin against Soviet aggression.

Today, America’s commitment to its allies is not so obvious. Would any American boast of being a citizen of Vilnius, Lithuania or Seoul, South Korea? After all, the very language of “national security” suggests that our nation – our homeland – ought to come first. Why should Americans fight and die to defend the rest of the world? Why not put “America First?”

In their 2016 book The Unquiet Frontier, Jakub Grygiel and Wess Mitchell attempt to recover the strategic rationale for our Eurasian alliances. The two demonstrate that our alliance system provides unparalleled benefits to the American people and warn us against complacency as revisionist states “probe” our allies for weakness. If we are unwilling to defend our allies, we will lose our credibility. If we lose our credibility, our allies will hedge against us. If our allies hedge against us, we will be unwilling to defend them. So begins a vicious cycle.

The book is an excellent strategic primer. But its arguments may have little appeal to those not already trained to think in terms of power politics. Many Americans, myself included, make sense of our national interests through the prism of our values. Therefore, I propose that we learn to translate the geostrategic case for alliances into the language of the American moral imagination — like Kennedy did in Berlin. We have no finer teacher in this than Alexander Hamilton, whose Federalist Papers persuaded us to embrace our first mutual defense treaty: the Constitution of 1787.

The Geostrategic Case for Alliances

Even in an age of renewed economic and military rivalries, does the notion that a foreign power might pose a direct threat to the United States seem far-fetched? The great powers of Europe and Asia are literally oceans away. Our military remains the most technologically advanced in the world. And – in the language of game theory – wars are negative-sum. Might America be more prosperous and secure if we weren’t entangled across the world? Grygiel and Mitchell disagree.

Figure 1: Map of U.S. “frontier” allies in Eurasia. [2]

The authors concede that geography offers the United States unique security advantages. But they also observe that American security has always depended on the balance of power in Europe and Asia. As early as the American Revolution – the age of sail – the colonists needed French naval support for a fighting chance against Britain. And for much of the nineteenth century, we relied on Britain to keep other European rivals out of the Western hemisphere.

The book’s basic thesis takes its bearings from geostrategist Nicholas John Spykman, an immigrant diplomat and political scientist. In 1935, Spykman founded the Yale Institute for International Studies to promote a vigorous American response to the fascist threat in Europe. A kind of proto-think tank, the Institute mailed its publications to thousands of American officials until its disbandment in 1951. It was at Yale that he devised the geostrategic theory behind the American alliance system.

Spykman’s analysis rests in turn on the insights of British geographer Halford Mackinder, whose landmark article The Geographical Pivot of History (1904) conceived of the modern world as a unified physical space. Whereas geography once divided human societies, Mackinder argues that the age of exploration (and European empire) brought all of humanity together under a single world-system. As such, he believed that political and military developments anywhere in the modern world would inevitably lead to reverberations elsewhere.

But Mackinder also believed that he was living through another world historical shift — one where industrial advances in land transportation would lead to the downfall of maritime powers like Britain. For centuries, Britain built an overseas empire on the back of its naval prowess, simultaneously conquering vast territories abroad as it maintained the balance of power on the European continent. This was possible because travel by water was much faster than by land. But with the advent of the railroad, Mackinder argued that any industrial power that controls the Eurasian “heartland” (Russia and Central Asia) would have the ability to drive Britain out from its coastal possessions (such as Egypt and India) and threaten the British Isles.

The argument goes as follows: if we imagine the Eurasian landmass as a circle, where Russia occupies the center and British territories sit along the edge, then the British would always travel longer distances to reinforce their positions than the Russians would need to attack them. This is because the seafaring British must move radially around the Eurasian landmass while railroads enable the Russians to cut straight through the interior. [3] And if rail is equally as fast as shipping, then the Russians (or whoever occupies the Eurasian heartland) can always mobilize faster than the British (or whoever sits at the Eurasian periphery).

Hence, Mackinder foresaw two nightmare scenarios for Britain (and the United States) emanating from the Eurasian continent. The first involves Germany combining with Russia to strike out at the Atlantic. The second involves Japan combining with Russia and China to strike out at the Pacific. Mackinder argued that hegemons of such scale, armed with modern technologies of war, would inevitably threaten outlying lands. Britain would be powerless to prevent their consolidation from afar given the diminishing advantages of sea power. He thus anticipated the course of World War Two, when Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan threatened Britain and the United States.

World War Two validated for Spykman the broad strokes of Mackinder’s analysis. Observing that the Old World is “two and one half times the size of the New World … ten times the size [in population]; and [equal] in terms of energy output,” Spykman prescribed a proactive policy of stationing American forces in Eurasia as it “would be cheaper in the long run to remain a working member of the European power zone than to withdraw for short intermissions to our insular domain only to be forced to apply later the whole of our national strength to redress a balance that might have needed but a slight weight at the beginning.” [4][5]

Thanks to Spykman and likeminded thinkers, American leaders after World War Two recognized that the Eurasian balance of power would not preserve itself with the Soviet Union on the rise and the British Empire in decline. This shift led the United States to develop alliances and forward positions in the Eurasian “rimlands.” Today, that system rests on mutual defense treaties with dozens of countries, not to mention tacit agreements with states like the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Ukraine. [6] Allies and certain other partners alike also enjoy the protection of our nuclear umbrella. [7]

Since 1945, American alliances have kept the “Long Peace,” securing prosperity for the American people and allied nations. We can take pride in that our security rests on sovereign allies, not colonial subjects. We ended the age of empires. Global trade travels unimpeded on the high seas. There are no more exclusive spheres of influence. And yet, even so, Chinese and Russian leaders are returning today to the dream of Eurasian integration, hoping to break out from under the world America made. Mackinder’s nightmares live again.

The Problem Restated: Political Will and the Moral Imagination

If we fail to live up to our commitments today, Grygiel and Mitchell warn, then our allies will accommodate themselves to aspiring hegemons impatient to restructure the world order. Our generation’s challenge is to reaffirm the importance of American alliances against a waning public appetite for foreign engagement.

National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster took up many of Grygiel and Mitchell’s ideas in the 2017 National Security Strategy. [8][9] But this strategic revolution at the top does not go far enough. Theoretical clarity can run a bureaucracy but cannot educate the public on the national interest. To do so demands an appeal to the moral imagination, that human capacity – mediated through tradition and culture – to peer beyond private interest, to feel honor and shame, and to sacrifice. Kennedy for example, spoke of West Berlin as “our city” — a city that represents the finest aspirations of a shared Transatlantic heritage.

What common story knits together Americans and our European and Asian allies? What do we have in common that is worth fighting for? Who are “we?” Taking stock of the intellectual history of “the West” as an idea in foreign policy, historian Michael Kimmage argues that cultural leaders and statesmen should reassert the geopolitical meaning of “the West” as a liberal-democratic alternative to authoritarian domination. [10]To include non-European allies like South Korea, Kimmage imagines a renewed “West” anchored in a broadly Euro-American model of democratic governance.

Can such an amorphous story, rooted in resemblances between political systems, capture the American imagination? Maybe ideologically — but not deeply into the moral imagination. The idea of “the West” had such power in the twentieth century because it wedded a transatlantic moral imaginary (of Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian roots) to the geostrategic threat to “the East.” Western solidarity rested on this moral-strategic convergence.

We need a mental map that can morally and geographically orient the United States toward the strategic realities of the present moment. Today, NATO’s eastern flank reaches far deeper into Europe, while our most capable allies and competitors are not across the Atlantic but the Indo-Pacific. Grygiel and Mitchell give us a map in the Mackinderian tradition that highlights our “frontier allies” in the Eurasian “rimlands”. But can we affix moral content to it – a sense of loyalty and identity – to states as diverse as South Korea and Lithuania? Or, for that matter, with non-treaty allies like Saudi Arabia? The authors offer a useful geostrategic picture, but not a moral one.

The United States Constitution: Hamilton’s Strategic-Moral synthesis

So how can we wed strategic and moral concerns in a post-Atlantic world, while opposing the “post-Western” political orders envisioned by rivals like China or Russia? Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger has lamented that American foreign policy has an idealistic, legalistic, and pragmatic tradition, but not a geopolitical tradition. This is not quite right. We do not lack tough-minded strategic insight, but the American moral imagination does fixate on ideals of liberty, law, and compromise — and for good reason. Strategy and morality, however, are reconcilable. We see this most clearly in Alexander Hamilton’s security arguments for North American unity in The Federalist Papers.

Like our alliance system today, the geographical extent and political diversity of North America created challenges for unity during the early republic. When Daniel Shays’s rebels swept through Massachusetts in 1786, Congress failed to raise an army, though the Articles of Confederation stipulated that the United States were bound “to assist each other, against all … attacks made upon them.” [11] The merchants of Boston had to finance a private militia themselves.

Shays’s Rebellion led the framers of the Constitution in 1787 to propose a powerful federal government that would tighten the bonds of union, protecting the states, its “alliance members.” Along with James Madison and John Jay, it was up to Hamilton to summon the moral imagination of the American people in support of this new “alliance” system. Like Spykman, Hamilton wrote within a tradition of political geography. He took his bearings from Montesquieu, whose analysis of regimes sought to reconcile the twin goods of liberty and security.

Montesquieu’s most consequential claim was that the logic of geostrategy forces large polities to centralize decision-making. But monarchy, Montesquieu’s preferred regime type, was rejected in the American revolution. His other solution – a confederacy of republics – was equally discredited by Shays’ Rebellion. The framers thus decided that they would have to devise a new form of government to secure American liberty.

Without the union, Hamilton and Jay argued in Federalist 3-9 that North America would divide into petty states jockeying for power. They would be vulnerable to rebellion, secession, and external threats. The states overcame all three during the American Revolution, but only under the exceptional leadership of George Washington and with European aid.

American prosperity also depended on access to foreign markets. To ensure that American commerce continues unhindered, Hamilton argued in Federalist 11 that a new North American union would provide Americans with more bargaining power in trade negotiations and the material basis for a strong navy. This basic insight remains the guiding principle of American foreign policy today: America loses without a flourishing foreign commerce.

With all this in mind, Hamilton conceived of a national geostrategic interest. He wrote that “the world may politically, as well as geographically, be divided into four parts, each having a distinct set of interests. Unhappily for the other three, Europe, by her arms and by her negotiations, by force and by fraud, has, in different degrees, extended her dominion over … Africa, Asia, and America.” [12] Hamilton saw that commerce made North America a single interconnected space, just as Mackinder would conclude of the world a century later.

Hamilton then couched the “American interest” in the moral language of anti-colonialism:

Facts have too long supported these arrogant pretensions of the Europeans. It belongs to us to vindicate the honor of the human race, and to teach that assuming brother, moderation. Union will enable us to do it. … Let Americans disdain to be the instruments of European greatness! Let the thirteen States, bound together in a strict and indissoluble Union, concur in erecting one great American system, superior to the control of all transatlantic force or influence, and able to dictate the terms of the connection between the old and the new world!

The Federalist Papers thereby frames the geostrategic dilemmas of the Thirteen Colonies in the moral language of liberty (freedom from European domination), law (binding the states), and compromise (being able to dictate terms to European powers). The proposed Union is a synthesis of rights-oriented idealism, constitutional legalism, and political pragmatism. A renewal of American foreign policy today requires statesmen and educators to reach into these same sources of moral imagination to bind us to our friends across the Atlantic and Pacific, just as Hamilton, Madison and Jay bound the thirteen states together.

Toward a More Perfect Union

Although the strategic landscape is utterly different today, we can still find the moral inspiration we need in a source familiar to Hamilton: the Constitution. Few realize that America’s founding document is also the legal bedrock of our alliance system. Article VI specifies that: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” [13] While successive American governments have license to enter and leave treaties at their discretion, a plain reading of Article VI suggests that abandoning our treaty allies by failing to fulfill our treaty obligations is tantamount to betraying the Constitution.

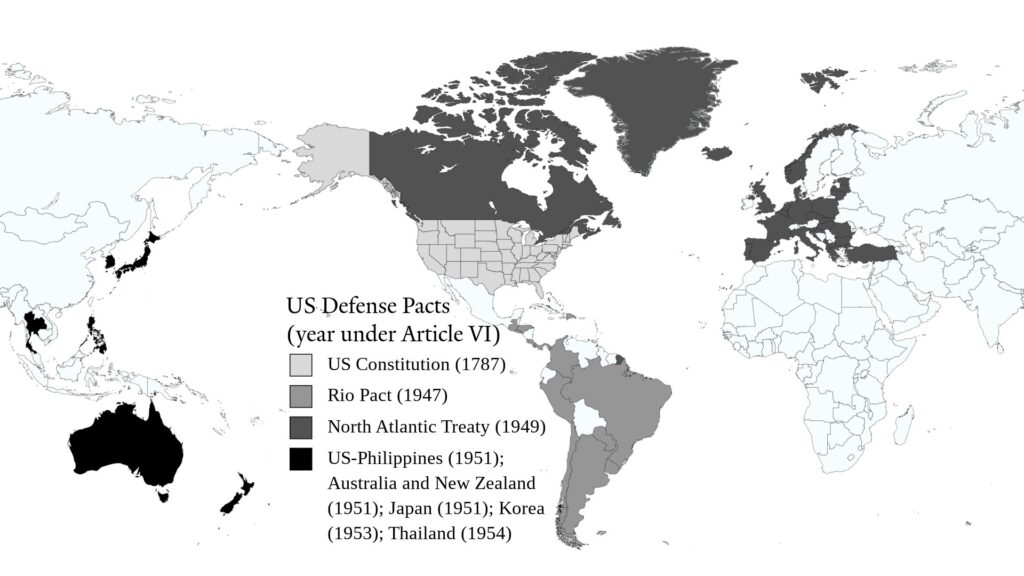

Figure 2: Map of U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty Allies.

A new but familiar world picture springs from this fact: a federation of states with legal obligations to defend one another. The Constitution is the mother of all mutual defense treaties, the first erected against Eurasian hegemony. Our alliance system today is created in its image. Just as Hamilton and the framers devised a uniquely American solution to Montesquieu’s geopolitical challenge, so too did Spykman answer Mackinder’s with a legal compromise that balances our ideals of liberty and our need for security.

This ultimately leads us beyond Grygiel and Mitchell’s visualization of our alliance system as a vast frontier in Eurasia in two respects. First, an intelligible map of our alliances must spatially relate Eurasia to the United States to suggest the underlying geostrategic logic. Second, we ought to make the moral distinction between treaty allies and other security partners. A map that includes non-treaty allies dilutes the constitutional basis of the American alliance system and risks overextension.

Luckily, Spykman provides a rather prescient map that we can build on in his Geography of the Peace (1944), entitled “The Western Hemisphere Encircled”. [14] The U.S.-centered map underscores the logic of our Transpacific alliances much better than Europe-centered maps. I have also filled in the map to highlight only U.S. treaty allies, thereby distinguishing our inviolable moral obligations from more ambiguous strategic interests. I also designate the Constitution as a mutual defense treaty between the fifty states, suggesting continuity in American foreign policy from the founding to the present day.

It will certainly take more than a clever map to convince the American people that our allies are worthy of sacrifice. But if the spirit of the age compels us to look to “America First,” then let us reflect upon the roots of our constitutional order and the alliances it upholds. By reuniting the geostrategic and mora dimensions of American foreign policy, we can begin to think about the sovereignty of our allies – in an era when East and West have lost their meaning – in terms of our commitment to the supreme law of our homeland.

If being an American patriot means honoring the Constitution, then we as patriots must stake our sacred honor on the sovereignty of our treaty allies.

Alex Hu ’23 is President Emeritus of the AHS chapter at Yale University, where he is majoring in Humanities.

—

Notes:

[1] John Fitzgerald Kennedy, “Berlin Wall Speech,” 26 June 1963, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/sites/default/files/inline-pdfs/JFK%20Berlin%20Speech.pdf.

[2] Jakub J Grygiel; A. Wess Mitchell, The Unquiet Frontier (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 2.

[3] Halford Mackinder, “The Geographical Pivot of History,” The Geographical Journal, Vol. 23, No. 4, April 1904, 421–437.

[4] Nicholas John Spykman, The Geography of the Peace (San Diego, CA: Harcourt, 1944), 33.

[5] Nicholas John Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics (San Diego, CA: Harcourt, 1942), 467-68.

[6] United States Department of State, “U.S. Collective Defense Arrangements,” State Department Website, https://2009-2017.state.gov/s/l/treaty/collectivedefense/index.ht.

[7] Council on Foreign Relations, “The Nuclear World,” World 101, https://world101.cfr.org/global-era-issues/nuclear-proliferation/nuclear-world.

[8] Uri Friedman, “The World According to H. R. McMaster,” The Atlantic. January 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/hr-mcmaster-trump-north-korea/549341/.

[9] Herbert Raymond McMaster, “Probing for Weakness,” The Wall Street Journal, 23 March 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/probing-for-weakness-1458775212.

[10] Michael Kimmage, The Abandonment of the West (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2020).

[11] Articles of Confederation, Article III, November 1777.

[12] Alexander Hamilton, Federalist, no. 11, November 1787.

[13] The U.S. Constitution, Article VI, September 1787.

[14] Nicholas John Spykman, The Geography of the Peace, 33.

Image: “Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States,” by Howard Chandler Christy, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scene_at_the_Signing_of_the_Constitution_of_the_United_States.jpg, permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document as this work is in the public domain in the United States because it is a work prepared by an officer or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties under the terms of Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 105 of the US Code.