Improvements in artificial intelligence (AI) will benefit wealthy states who develop national programs, potentially leading autocracies to utilize emerging technologies in threatening ways. Consequently, democratic states must consider the risks that these technologies can pose to liberal norms, while simultaneously working to constrain autocracies’ use of AI systems.

AI-driven technological advancements may threaten the international community in several ways, most notably in information control and dispersal, weapons systems and military technologies, and surveillance and intelligence collection mechanisms. AI presents unique risks, given its nature and nonhuman elements, and lacks pre-existing principles or norms surrounding its use. However, some argue that the historical soundness of states’ goals and policies amidst technological change, paired with the power of democratic institutions and liberal state collaboration, will balance AI’s benefits across regime types. Going forward, democracies must prioritize research, international cooperation, and norm-building to mitigate the threat of AI advancements in autocratic states, while also recognizing the universal benefits of these technologies.

The Current Landscape

AI technology is in its nascent stages, causing policymakers and military leaders to consider the potential capabilities and risks that advancements would bring. Global superpowers have begun to formulate national AI strategies, outlining goals and preliminary norms for how research and development will progress. However, it is already clear that democracies and autocracies diverge, and will continue to diverge, on how they expect AI to serve their national interests. Many states have begun to consider the positive uses of AI, such as advancements in health, education, and entertainment, but governments vary in their acknowledgment of the potential risks. Even democracies have had difficulties accounting for flaws in AI systems, which can lead to enormous impacts on their citizens, such as wrongful imprisonments or medical diagnoses. Nevertheless, autocratic states’ AI policies will parallel their political initiatives to centralize and consolidate government power, to control and surveil their domestic population, and oftentimes, to undermine democratic states abroad. Democracies must address a wider range of considerations in order to reap the potential benefits of emerging technologies while preserving liberal values and individual freedoms.

The widespread development of AI systems poses a significant risk to democratic norms, as programs can threaten human agency while allowing autocracies to better centralize power, exercise public control, and undermine the democratic norms of freedom and liberty. [1] In this respect, AI benefits autocratic governments, giving them greater oversight, control, and military capabilities. In terms of research and development, autocracies also benefit from required collaboration with domestic technology companies and tech talent, which democracies often lack.

New AI technologies can exacerbate existing threats such as invasive censorship and surveillance practices, while changing the character of threats, as seen with weapons systems that are not human-run. Autocratic states’ AI development will also likely introduce new threats as governments seek to advance their interests, which are more difficult to project. [2] Academics like Edward Geist have also considered whether the current state of global AI competition will result in an ‘AI arms race’ between superpowers or regime types, as the struggle to advance technologies and to establish norms persists. [3] Regardless of the standards that democratic states set, autocracies will utilize AI to control their domestic populations and to interfere with foreign actors. Democracies must recognize that AI may impact liberal governance models and take active steps to counteract this phenomenon.

AI is a rapidly growing field, as new applications for the technology increase every year. However, it can be difficult to assess when certain capabilities will be possible and to plan accordingly. As of 2021, ‘narrow AI’ (programs that accomplish a single human task) encompasses most existing technologies, which may evolve into ‘general AI’ (programs that can accomplish a wide variety of human tasks) in the foreseeable future. AI advancements may eventually produce superintelligent AI within the next several decades, which AI scholar Nick Bostrom defines as “an intellect that is much smarter than the best human brains in practically every field” [4]. It is important to consider the implications of both general and superintelligent AI, as these complex developments may exist in the near future.

Risks to Democratic Systems

AI presents new threats in the information sharing sphere, particularly with respect to disinformation. On a global scale, information and news sharing are predominantly conducted online – a trend that will likely continue in coming years. Autocratic states have increasingly adopted disinformation strategies that target both domestic and foreign populations, following the global visibility that Russia’s disinformation practices received in 2016. China and Iran will also likely expand on their information programs in the future, which AI advancements will support. New technologies will help to improve the speed and quantity of information disseminated through bots, while allowing actors to create more realistic fake images and videos using generative adversarial networks (GANs) – a type of unsupervised learning that can be trained to generate fake content, fueling the disinformation market. [5]

AI will also allow users to more effectively analyze online data, improving the targeted spread of disinformation and autocratic content online. Targeting audience analysis is a key factor of disinformation efforts, as autocracies seek to categorize online users based on their personal data. AI will help governments to improve data aggregation and analysis efforts, leading to more effective targeted disinformation campaigns. As these practices are deployed beyond the borders of authoritarian regimes, shots from behind the ‘Great Chinese Firewall’ will likely become a topline security risk for the United States and its allies. While AI will help democratic states to combat this threat, disinformation will remain difficult to defend against as technology companies and governments continue their struggle to detect and disarm bot accounts, trolling efforts, and fake news from infecting online platforms. As AI threatens the information landscape, democratic governments will also need to prioritize private sector coordination, international partnerships, and the implementation of defensive AI programs to help combat this problem.

Autocratic states also commonly engage in censorship practices, which pose less of an international risk than disinformation, but should still be considered. Advancements in AI will allow autocracies to more effectively censor domestic news outlets, online sites, and even public discourse. Online AI systems will lead to more rapid detection and deletion of unwanted commentary and will help governments to control the media that their citizens can view. New technologies will also provide more specific data on individuals’ personalities and ideologies, allowing governments to more easily threaten and censor potentially ‘dangerous’ voices. This grates against the liberal norms of freedom of speech and expression and may cause citizens of autocratic regimes to be misinformed about global events and their domestic political situation.

AI will also lead to further advancements in weapons systems, which pose significant risks to the global community. Democratic systems have initiated conversations on the legality and development of lethal

weapons systems, as many states have already outlawed their use. [6] Providing a ‘human in the loop’ may decrease the speed and effectiveness of weapons but would ensure a more measured and safe use of these systems. However, autocracies may ignore safety mechanisms in order to gain military advantage or if these measures decrease weapon efficiency. The ‘black box problem’ of AI is particularly relevant to this sector, as leaders’ misunderstanding of the limitations and risks of AI-run weapons, cyber programs, or intelligence applications could endanger large populations. Autocratic states may be more inclined to ignore safety issues, especially if military superiority is on the line.

While many democratic states, particularly the United States, retain superior military capabilities, autocratic governments like the People’s Republic of China will likely ignore whatever international consensus and legal standards develop around these technologies to optimize their capabilities. Democracies may struggle to form internationally-accepted norms and restraints on AI-run weapons, but military advancements have long progressed without unduly favoring autocratic states. Even with the complex creation of nuclear weapons, states were able to cooperate and establish principles surrounding their use. Regulations for lethal autonomous weapons will hopefully bring similar practices, as long as humans are able to remain ‘in the loop’, preventing these weapons from escalating conflict past the point of human control. However, it remains largely unknown how autocracies will exercise and limit these new military technologies, especially given the lack of internationally-accepted norms on the subject.

Finally, AI technologies assist governments with surveillance, benefiting autocracies as they seek to centralize power while monitoring potential threats to their regimes. Autocratic states like China have utilized technological advancements to improve surveillance through monitoring online activity, establishing a social credit system, and practicing invasive monitoring of minority populations like the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. AI will expand on existing systems, allowing governments to monitor their citizens with unprecedented levels of precision. Within the next decade, states will also have access to larger, well-interpreted data sets – a key pillar of AI technologies. This will allow autocracies to expand their surveillance programs while amplifying efforts to analyze, categorize, and potentially exploit populations. This may lead to a variety of human rights violations, as political disruptors, minorities, and other groups are targeted. [7]

As surveillance practices are not exclusive to autocracies, the intelligence and ethical implications are important for all states to recognize. While certain surveillance technologies like facial recognition services may appear to have widespread benefits, they also hold underlying biases and flaws that governments must account for. AI advancements may also help governments to expand and improve their surveillance efforts outside their domestic borders, which carries significant intelligence implications. Living in a world of hyper-surveillance, by domestic or foreign governments, strays from core liberal principles and may change the nature of international politics and information collection.

Looking Ahead

New technologies often provoke strong reactions, as many believe advancements have ‘the ability to change everything’. However, military strategies, political proclivities, and cultural norms remain relatively consistent with time, in both democratic and autocratic states. So why would AI advancements be any different? Even with these new technologies, democracies will likely continue their practice of improving military capabilities while managing their opponents. When faced with developments in information warfare and surveillance, democratic states will continue to fortify their own defenses, while working to disseminate global norms. Liberal governments will continue to spread values of liberty and freedom to their domestic audiences, as their federal surveillance and censorship practices remain limited. In other words, AI may not necessarily lead to a major shift in power or policy, as states have remained somewhat consistent for centuries. However, many also argue that AI is ‘unprecedented’ as it can remove human control and involvement in certain sectors, machines, and jobs for the first time. While new weapons systems and technological advancements have not truly jolted the international community for some time, the humanless element of autonomous systems may have the ability to change life as we know it.

Another argument in support of AI’s benefits for democracies examines the strong partnerships that democracies foster. Democratic states are known for creating strong alliances with one another, as shown through the international institutions, formal partnerships, and political unions that support liberal states. While autocracies work to exert influence abroad, they are often more insular, relying on domestic talent and espionage rather than collaborative efforts. Democracies will be able to excel in the AI sphere, while managing autocratic regimes, if they are able to coordinate on technological advancements, data and intelligence sharing practices, and the crafting of ethical standards.

However, democracies like the United States need to implement several domestic changes to address the rapidly growing global AI competition. For example, the Department of Defense’s military budgeting process should modernize the defense acquisition process for adopting emerging technologies. The current decision and fielding time of new systems often takes more than ten years, while China and Russia release technologies more quickly, given their lack of bureaucratic restraints and China’s iterative and adaptive military development approaches. [8] Eric Schmidt, a co-chair of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, stated that the United States is only “one or two years ahead of China” in the area of AI and that the U.S. government should implement a time-efficient and competitive approach to AI development. [9] Coordination and R&D sharing with other liberal states would help the United States and its allies to more quickly develop AI systems and the norms surrounding them. Additionally, working alongside powerful institutions like the United Nations would aid democratic states in managing the exploitation of new technologies. Creating international treaties and groups, such as the OECD–G-7 Global Partnership for AI, [10] and implementing economic or political consequences for noncompliance would help to limit autocracies’ misuse of technology. Although potential AI advancements of the next decade are unlikely to bring existential or widespread threats to the international community, it is important for democracies to work quickly to mitigate this problem that lies in the near future.

The nature of AI systems benefits autocratic states, given the lack of human agency and the technology’s ability to help centralize government control. It is therefore essential that democratic states work quickly to establish partnerships, both domestically and internationally, and norms surrounding the use of AI systems. Democracies should also dedicate resources to researching the potential risks of emerging technologies across sectors, which will allow policymakers and military personnel to better forecast the future threat landscape. [11] Democracies must actively work to counter the autocratic benefits of AI but may also reap the extraordinary benefits of these technologies.

Hannah Delaney previously served as an intern in AHS’s National Office and received her MA from Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program in 2021.

–

Notes:

[1] Yuval Noah Hariri, “Why Technology Favors Tyranny,” The Atlantic, October 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/10/yuval-noah-harari-technology-tyranny/568330/.

[2] Miles Brundidge, et al., “Malicious Uses of AI: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation,” (Oxford: Future of Humanity Institute, February 2018), https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.07228.pdf.

[3] Edward Geist, “It’s Already too Late to Stop the AI Arms Race-We Must Manage It Instead,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 15 August 2016.

[4] Tim Urban, “The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence,” Wait But Why, 22 January 2015, https://waitbutwhy.com/2015/01/artificial-intelligence-revolution-2.html.

[5] Martin Giles, “The GANfather: The Man Who’s Given Machines the Gift of Imagination,” MIT Technology Review, 21 February 2018, https://www.technologyreview.com/2018/02/21/145289/the-ganfather-the-man-whos-given-machines-the-gift-of-imagination/.

[6] Brian Stauffer. “Stopping Killer Robots,” Human Rights Watch, 10 August 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/10/killer-robots-growing-support-ban.

[7] Chris Buckley, et al., “How China Turned a City into a Prison,” The New York Times, 4 April 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/04/world/asia/xinjiang-china-surveillance-prison.html.

[8] William Greenwalt, Dan Patt, “Competing in Time: Ensuring Capability Advantage and Mission Success through Adaptable Resource Allocation,” (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute, February 2021), https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.hudson.org/Patt%20Greenwalt_Competing%20in%20Time.pdf.

[9] Joe Gould, “Pentagon’s Dated Budget Process Too Slow to Beat China, New Report Says,” Defense News, 25 February 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/congress/2021/02/25/pentagons-dated-budget-process-too-slow-to-beat-china-new-report-says/.

[10] Audrey Plonk, “The Global Partnership on AI Takes Off – at the OECD,” OECD.ai, 9 July 2020, https://oecd.ai/wonk/oecd-and-g7-artificial-intelligence-initiatives-side-by-side-for-responsible-ai.

[11] Brundidge, et. al.

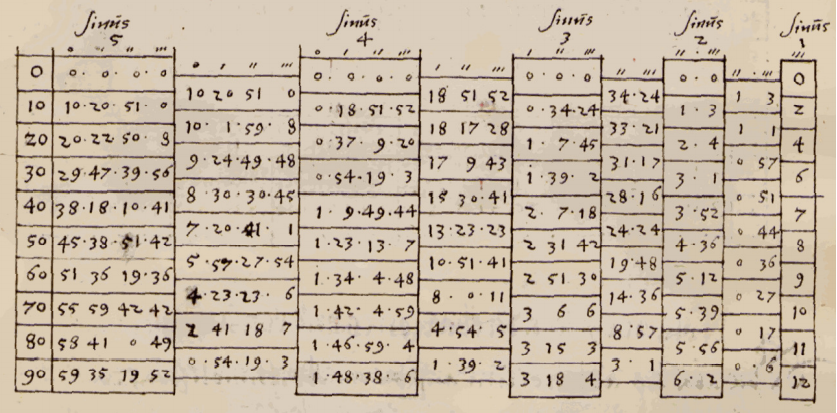

Image: “Jost Bürgi (1592) from Fundamentum Astronomiae, Biblioteka Uniwersytecka de Wroclaw”, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kunstweg_(Jost_B%C3%BCrgi).png, image is in the public domain.

Your support is critical to our programming on college campuses and in cities across the country. Donate $50 and you will receive a printed copy of The Hamiltonian.