Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has generally aimed, at least rhetorically, to create foreign policies that strive to maximize freedom in other countries, employing a wide swath of policies ranging from development assistance to military intervention. A key way that countries promote liberal democracy is through international, or intergovernmental, organizations. International organizations could more efficiently promote democracy, however, by better understanding which countries stand most to benefit from election assistance programs.

Freedom House and its Rubric

A good indicator of a country’s levels of freedom and democracy is the annual Freedom House Freedom in the World (FIW) report, for 2020 entitled “A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy.” The report famously rates each country 0-100 based on its level of freedom. Each country’s score is made up of 25 subscores, in which a country is rated 0-4 in different categories relating to political rights and civil liberties. These categories are based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In addition to the overall score, each country is put into one of three broad buckets describing its level of freedom: Free, Partly Free, or Not Free. [1] Freedom House’s rankings are widely used and praised by scholars, and even critics acknowledge that systemic bias in the rankings is hard to find. [2] Furthermore, studies have found that Freedom House’s rankings highly correlate with those from other studies measuring democracy. [3]

International organizations can use a country’s FIW score to help determine where to spend resources on democracy-promotion initiatives. Since one of the goals of international organizations is to get as many countries as possible into the “free” category, they should act strategically about which approaches to use. Correctly identifying where to efficiently spend resources depends on assessing how the benefits that intergovernmental organizations provide align, or do not align, with a country’s needs.

First, this requires finding those transitioning democracies – generally, those countries deemed “partly free” in the FIW report – where a surge of resources and assistance from international organizations has a higher chance of moving a country into the “free” column. A country like Syria, for instance, with a FIW score of 0, is unlikely to be the most efficient use of resources for those looking to increase the number of liberal democracies. On the other side of the spectrum, spending resources on a country that is already a stable democracy like Uruguay (FIW score 98) is also unlikely to be most efficient.

The Missing Second Element: Alignment

There is an often-neglected second element in this expenditure calculation that should be taken into account: a country’s needs must align with the services that international institutions can provide. While it would be challenging for an international organization to promote a right like “freedom of expression” in another country, international organizations have a range of tools to address other challenges to freedom, particularly around elections. Through election monitoring and election administration assistance, international organizations can help improve election quality in a country. Though each international organization has different roles and capabilities, those capabilities generally fall into three main categories: election observation, where an international delegation is sent to monitor an election; technical assistance, where an organization assists with logistics or legal procedures; and supervision, certification, and verification, which acts as a stronger form of “observation” where the international organization is tasked with fully legitimizing an election’s results. [4]

Thus, the countries in which the assistance of international organizations can most efficiently help create stable, liberal democracy are those countries with mid-range levels of freedom and in which election quality notably lags behind the overall level of freedom. Electoral assistance to these countries could make a substantial difference in increasing the number of liberal democracies in the world.

The Rubric Adjusted: A New Index

In order to assess which countries these are, I combined the FIW dataset with the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) dataset from the University of Sydney and the Harvard Kennedy School. The PEI data has a series of election experts rank the integrity and quality of elections around the world based on a series of indicators. The rankings for each indicator are then incorporated into an overall election quality score for each country. [5] To maintain consistency in this paper, I only included those countries in my analysis with up to date FIW and PEI scores: a net 133 countries for analysis. [6]

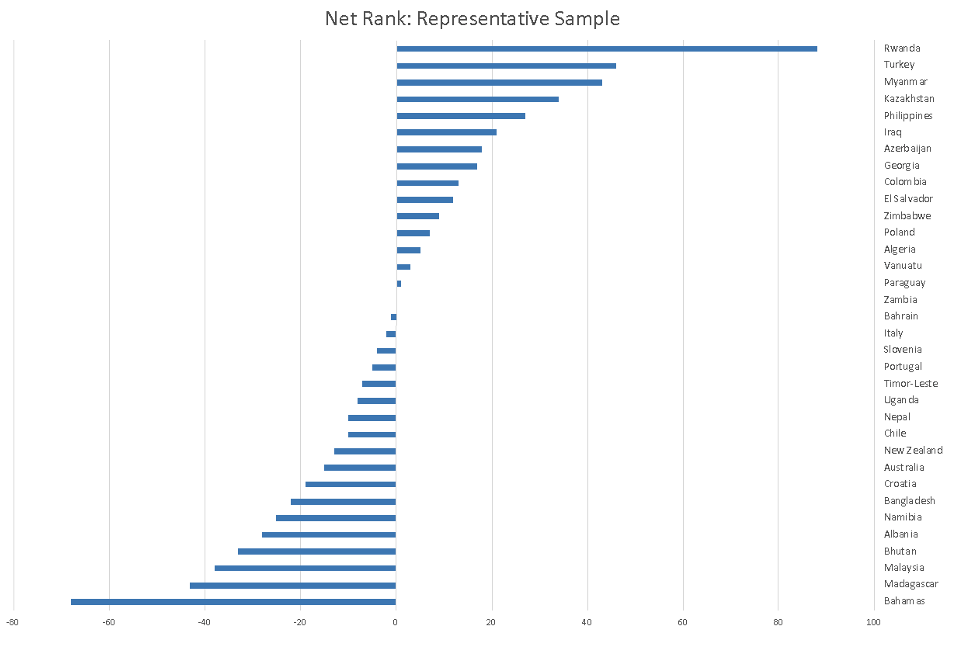

To evaluate which transitioning democracies have an election quality that falls disproportionately below their overall level of freedom, the countries in my sample were given a ranking 1-133 for their level of freedom according to their FIW score (known hereafter as their “freedom rank”) and for their election quality according to their PEI scores (“election rank”). Then, the election rank for each country was subtracted from its freedom rank, giving each country a freedom rank minus election rank score (“net rank”). That score will be the basis of this analysis. Countries with a higher net rank have a level of freedom disproportionately higher than what would be expected based on their election quality; for countries with a lower net rank the opposite is true. Figure 1 shows a representative sample of about one-quarter of the countries being studied.

Figure 1.

The net rank varied dramatically. This variation makes sense, as an R2 analysis found that only 61.4 percent of the variation in freedom rank can be explained by a country’s election rank. Some countries, like Paraguay and Italy, had freedom ranks that closely mirrored their election ranks, indicating that their election quality is proportional to what one might expect based on their overall level of freedom. Other countries, like Rwanda, have an election quality that far exceeds their overall level of freedom. Still others, like Madagascar, have the opposite effect, with election quality proportionally being far below overall freedom in the country.

When investigating any individual case in more depth, the reasons behind a discrepancy often reveals themselves. Notwithstanding its recent events, the example of Myanmar (Burma), which had a net rank of 43, makes this case well. The score of 43 signifies that election quality in the country is significantly better than the overall level of freedom. Since 2015, Myanmar has had relatively free and fair elections, but because of the structure of their 2008 constitution, the military maintains disproportionate control of government (though this section was drafted prior to the military coup, it serves to highlight this point). Furthermore, the Bamar majority in Myanmar holds all the power, often restricting the rights of Myanmar’s many ethnic groups. [7] Though just one example, Myanmar demonstrates why this discrepancy between election rank and freedom rank can exist.

The next step in the analysis involved limiting the sample to only “transitioning” democracies, where interventions from international organizations have the best chance at moving them to the “free” column. I limited the sample to those countries with FIW scores between 25 and 80. On the low end, this change meant eliminating 21 countries, including Syria, Venezuela, Rwanda, and Vietnam. On the high end, it meant eliminating 44 countries, including all of Western Europe, but also countries like Japan and Ghana. After these subtractions, 67 countries remained in the sample. These remaining “partly free” countries still exhibited remarkable range, from Cambodia (FIW Score: 25) to South Africa (79).

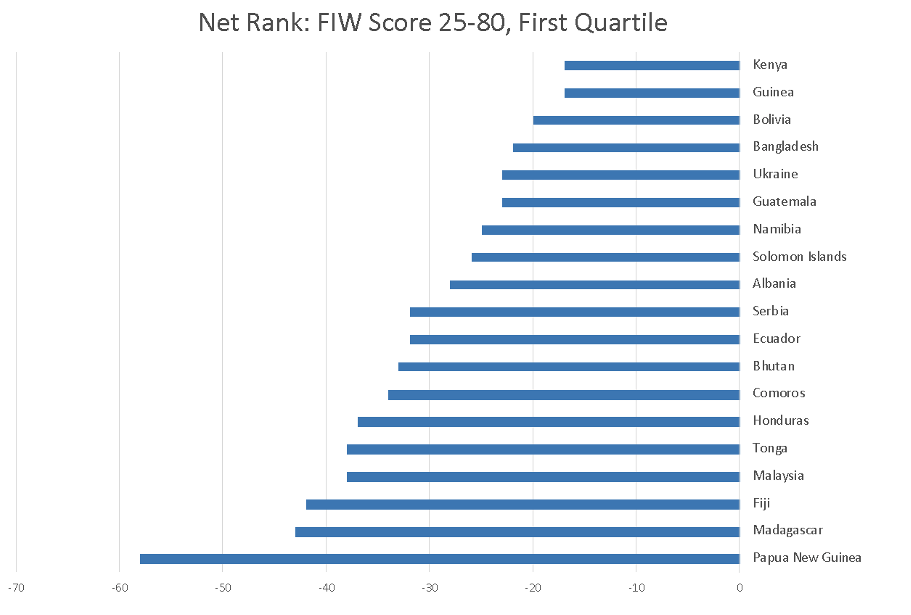

Most interesting for this analysis, however, are the countries with net ranks in the lowest quartile – that is, those transitioning democracies whose freedom rank exceeds their election rank by at least 15. For these countries, the quality of their elections is significantly below what would be expected based on their overall level of freedom. Because only the lowest quartile is used, the exact freedom rank or election rank of a country matters far less than the overall comparison between the two. Figure 2 shows those 19 countries.

Figure 2.

A wide range of countries still remain. Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas are all represented – although, notably, no countries from the Middle East remain. The FIW scores for these countries range from 39 (Bangladesh) to 79 (Tonga and the Solomon Islands). They tend to be poorer than the overall sample in terms of GDP per capita (a median of $6,662 for these countries compared to $13,022 overall). [8] A wide range of income levels exists within the subset, however, with Malaysia having about 20 times the GDP per capita of Madagascar. The population sizes of these countries also vary drastically. While five of the countries have populations of less than 1 million, Bangladesh has a population of 165 million. These countries also receive different amounts of foreign aid. While Bangladesh receives $3.5 billion in foreign aid annually, Bhutan only receives $21 million. And while Tonga receives a whopping $775 per person in aid, much larger Malaysia only receives about $1.56 per person. [9] International organizations should focus their election integrity efforts on these 19 countries, for helping to improve their election quality will most efficiently use the limited resources of intergovernmental organizations to create and strengthen as many free, liberal democracies as possible.

Some Illustrative Case Studies

A few case studies prove to be insightful. Bangladesh is the most populous country out of the 19, with a population of 165 million. It has a FIW score of 39 and a net rank of -22. Bangladesh’s 2018 parliamentary elections were filled with corruption, violence, and intimidation. The elections were so fraudulent that the primary opposition party chose to boycott the parliament. [10] According to Transparency International, 47 of the 50 constituencies it surveyed in Bangladesh had “irregularities” in their election process “including fake votes, ballot stuffing, and voters and opposition polling agents barred from entering polling centers.” [11] International election observers were effectively barred, however, from monitoring the election. While Bangladesh claims that they cooperated with international obligations, the U.S. State Department said that Bangladesh did not issue visas in time to observers. The EU chose not to send election observers, with EU Ambassador to Bangladesh Rensje Teerink saying the decision was made because an observation mission “requires a big number of observers and months of preparation. So, in budgetary terms, it’s quite expensive. And it takes a lot of effort and preparation.” She went on to say that the choice about which elections to monitor is “a question of prioritizing.” [12]

Yet should these not be the elections that the EU prioritizes? With improved elections, Bangladesh would make significant progress towards becoming a free democracy. It is also a populous country with a significant GDP located in a strategically-important area. While election monitoring will not solve all of the woes for democracy in Bangladesh, personal freedoms are relatively better protected in the country, and the constitution does guarantee the rights of association and assembly. [13] Some baseline for liberal democracy in Bangladesh exists, so it should be a priority for international organizations to provide their election monitoring and assistance services to the country to help it transition to liberal democracy.

Examining another example, Honduras, proves what can happen when there is significant intervention from international bodies. The country, with a net rank of -37, has been successfully identified by several international institutions as a prime target for election monitoring and electoral assistance. Its 2017 national election, according to the Organization of American States (OAS), “was characterized by irregularities and deficiencies, with very low technical quality and lacking integrity.” [14] A key difference between Honduras and Bangladesh, however, is that the elections in Honduras were heavily monitored. The U.S., EU, and OAS all sent observation missions to Honduras for the elections. [15] While the OAS’s call for new elections was not heeded by Honduran authorities, an agreement was reached by the OAS and Honduran government in 2018 to replace the country’s Supreme Electoral Council with a new, and more independent, Electoral Court of Justice and National Electoral Council to administer future elections. This agreement sets Honduras up for higher quality elections in the future. For a country with a FIW score of 45, improving election integrity could go a long way in moving Honduras towards becoming a free democracy – a process enabled and supported by election monitoring from international organizations.

Conclusions

Other countries outside of these 19 could still be worthy of receiving monitoring or other election assistance. Across the world, including here in the United States, improving the quality of elections can be valuable. Particularly in those countries whose election ranks were similar to their freedom ranks, there could even be cyclical effects of improving election quality causing improvement in other areas. Yet as the R2 analysis reveals, only 61.4 percent of the variation in countries’ freedom ranks is explained by countries’ election ranks, so this progress is likely to be imperfect. Election assistance in these countries can create positive change, but it may not be the most efficient usage of resources for international organizations.

This argument is further supported by a reasonable assumption: a country that already has strong civic freedoms is well-positioned to have higher-quality elections succeed. For example, if a country already has a free press, then that press could report on the transparency, or lack thereof, in an election. If this assumption holds, then investing resources in improving elections in these 19 countries whose freedom rank significantly exceeds their election rank has a high likelihood of triggering positive reinforcement effects.

Helping “partly free” countries become “free” is about more than a changed label – it has important implications for the people of those countries and for all other liberal democracies in the world. First and foremost, the 19 countries in the list have a combined population of well over 400 million people. Those people have an inherent right to good, transparent, and accountable government. As the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states, “The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.” [16] The genuine desire to improve people’s lives should always be the primary reasoning for countries looking to intervene abroad to improve freedom and democracy.

There are also a number of self-interested reasons why existing liberal democracies should seek to efficiently promote as many other countries as possible to that status. The most general of which is that liberal democracies are more likely to cooperate with each other. As the McCain Institute explains, “Free nations are more economically successful, stable, reliable partners, and democratic societies are less likely to produce terrorists, proliferate weapons of mass destruction, or engage in aggression and war.” [17] Furthermore, recent scholarship has revealed that while some degree of democratic backsliding continues, in general, countries today that become democracies are more likely to stay that way, with a sharp decline in coups d’état and fraudulent elections since the end of the Cold War. [18] There are also other implications to a country becoming a democracy, like having more votes for coalitions of liberal democracies in international governing bodies, that can add up over time.

International organizations have a unique ability to foster freedom around the world. One of their best assets is the ability to help improve election integrity through monitoring and other election assistance. Using this capability most effectively, however, requires figuring out where the capabilities of international institutions best align with countries’ needs. Through the analysis in this paper, 19 countries whose election quality was significantly below their overall level of freedom were identified. Expending electoral assistance resources on these countries where improved elections could have significant implications for their overall level of freedom would be a smart way for international organizations to most efficiently use their limited resources to enact positive change on the world.

Though the process proposed here focuses on election monitoring and assistance, it is indicative of a larger problem: many of the rubrics that countries and international organizations use to decide where to focus foreign affairs resources are outdated. Policymakers often define our “interests” in cost-benefit calculations too narrowly, restricted by logic that persists from the Cold War and War on Terror.

While it is understandable that countries often want to direct foreign investment to help achieve short-term objectives, this approach overlooks important opportunities to enact change that may be beneficial in the long run. Many international organizations are imperfect, but they have unique sets of capabilities that can be better matched with countries’ needs if we reimagine our interests with a broader, more long-term view.

Carson Maconga is President of the AHS Chapter at Princeton University, where he studies public and international affairs.

Notes:

[1] Sarah Repucci, “A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy,” (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2020), https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2020/leaderless-struggle-democracy.

[2] Kenneth A. Bollen, “Political Rights and Political Liberties in Nations: An Evaluation of Human Rights Measures, 1950 to 1984,” Human Rights Quarterly 8, no. 4 (1986): 567–91, https://doi.org/10.2307/762193.

[3] Scott Mainwaring, Daniel Brinks, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, “Classifying Political Regimes in Latin America, 1945-1999,” Studies in Comparative International Development 36, no. 1 (March 2001): 37–65, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02687584. See also: “Elections | Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs,” (New York: United Nations), https://dppa.un.org/en/elections.

[4] Pippa Norris, Thomas Wynter, and Sarah Cameron, “Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, (PEI-6.0)” (Harvard Dataverse, March 2018), https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Q6UBTH.

[5] Most omissions came from the PEI dataset, which does not include countries with less than 100,000 people or countries without regular, popular elections. Some countries only had outdated information, so for consistency, they also were omitted.

[6] Zolton Barany, “Armed Forces and Democratization in Myanmar: Why the U.S. Military Should Engage the Tatmadaw,” (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies, September 2016), https://www.csis.org/analysis/armed-forces-and-democratization-myanmar-why-us-military-should-engage-tatmadaw.

[7] Scaled for purchasing power parity. Sarah Repucci, “A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy,” Freedom House, 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2020/leaderless-struggle-democracy;

[8] Norris et al.

[9] “Aid (ODA) Commitments to Countries and Regions [DAC3a],” (OECD.stat, 2018), https://stats.oecd.org/.

[10] “Bangladesh,” (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2020), https://freedomhouse.org/country/bangladesh/freedom-world/2020.

[11] Zeba Siddiqui Paul Ruma, “Some in Bangladesh Election Observer Group Said They Regretted Involvement,” Reuters, 29 January 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-election-observers-exclusi-idUSKCN1PG0MA.

[12] Harun Ur Rashid Swapan, “Why the EU Isn’t Sending Election Observers to Bangladesh | DW | 31.10.2018,” DW.COM, 31 October 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/why-the-eu-isnt-sending-election-observers-to-bangladesh/a-46108294.

[13] “Bangladesh,” (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2020).

[14] “Honduras,” (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2020), https://freedomhouse.org/country/honduras/freedom-world/2020.

[15] “Honduras,” (Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2020).

[16] “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” United Nations, December 10, 1948, https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

[17] “Advancing Freedom Promotes U.S. Interests,” (Washington, DC: McCain Institute), https://www.mccaininstitute.org/advancing-freedom-promotes-us-interests/.

[18] Nancy Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0012.

Image: “John Cantiloe Joy – Going to a Vessel requiring assistance and Thereby preventing Shipwreck” by Amitchell125, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Cantiloe_Joy_-_Going_to_a_Vessel_requiring_assistance_and_Thereby_preventing_Shipwreck.jpg, image is in the public domain.

Charts: (Figures 1& 2) created and provided by the author.

Your support is critical to our programming on college campuses and in cities across the country. Donate $50 and you will receive a printed copy of The Hamiltonian.